The issue of turning off daylight when it is not being used is a good one. I have been an interior designer for many more years than I have been a LEED AP, and have been turning off excess daylight for a number of years by using window treatments.

Blog Post

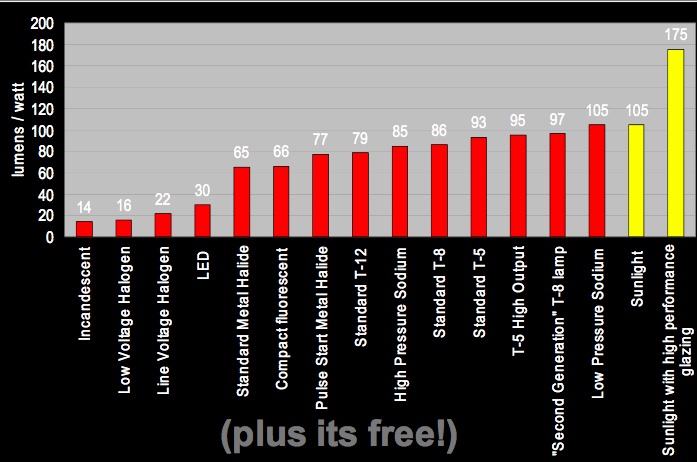

Getting more sunlight per watt

Sunlight gives us light at no charge, which we can harness in our buildings to reduce our reliance on electrical lighting, while providing a more enjoyable indoor environment.

Leave it to an engineer to tell us how much that sunlight actually costs us. Lumens per watt (lpw) is the measure of lighting efficacy, telling us how much light (lumens) we get out for how much power (watts) we put in. The chart below shows typical efficacies of different lighting technologies, including incandescent (14), LED (30–50), T-5 fluorescent tube (95), and more.

Published May 16, 2008 Permalink Citation

(2008, May 16). Getting more sunlight per watt. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/blog/getting-more-sunlight-watt

Comments

That's a thought-provoking pe

That's a thought-provoking perspective on the costs and benefits of natural lighting, and I'd like to see a little more details on the calculations behind it. For example, does it count the lumens of sunlight provided, or the desired/required lumens of artificial light that it would offset? Are the numbers all in site energy or in primary energy? The point of this comparison seems to be as part of the economic calculation of optimal glazing area, so I presume the units are "lumens offset per watt expended".

However, I have to take issue with the subtitle "plus it's free!" The very point of the calculation is to show how much additional energy must be expended on space conditioning (which is not free) when glazing area is expanded. In fact, not only is the energy for daylighting not free, but since you can't turn it off (the energy is expended whether or not the light is needed), it's "free" like the included minutes of your cell phone plan: you are going to pay the same amount per month regardless, so you might as well use as much as you can.

Thanks for the great little g

Thanks for the great little graph.All I wanted to know was if 2 ,12 watt florescent standard T-5 tubes be the equilivent to 1, 24 watt

hp T-5 tube. Your chart tells me yes, all other things being equal.

simple question hard to find answer. Must have visited 20 different sites before I got here. So thanks again.

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.