Thank you for your thoughtful blog. I am, however, having trouble with idea of former hominids being portrayed as the 'noble savage'.The Clovis possibly did a great job of decimating the megafauna once they got onto the fluted Clovis points. Probably little has changed in human nature over the millennia. As the quote goes Troy McClure:" Don’t kid yourself, Jimmy. If a cow ever got the chance, he’d eat you and everyone you care about!" I look forward to the next blog .Cheers

Blog Post

Small Can Be Beautiful – Use these principles to make it work

We continue our primer on building responsibly in the post-carbon era: How do we design to honor and support nature's patterns, rather than co-opting them?

[Editor's note: Robert Riversong, a Vermont builder, continues his 10-part series of articles taking design and construction to what he sees as radical or "root" concerns. Enjoy--and please share your thoughts. – Tristan Roberts]

2. Design – elegant simplicity, the Golden Mean

In the most fundamental sense, design is how we organize our environment to meet our needs, whether those needs are functional or aesthetic or spiritual (which are often indistinct from one another). It has been suggested that human culture, and consequently human design, has shifted from a phase of dependency on nature to a period of independency from nature.

In the former phase (99.8% of our evolutionary history), we lived very gently on the land, typically meeting our basic needs as simply and lightly as possible. In the latter phase, which we call "history" or "civilization", we sought to conquer nature and use her for our own purposes, often imposing grand structures and edifices upon the land and creating our own local environment and enclosed microclimate – typically to the detriment of the natural environment and now even the global climate.

The Greening of Design

It is also becoming more widely understood, within the progressive design community, that we must now shift once again--to a phase of interdependency or partnership with our environment. This relatively recent progression, which could perhaps be dated to Earth Day 1970, can be interpreted as going from Industrial Design (readily manageable uniformity, which remains our dominant paradigm), through Efficient Design (reducing energy inputs), Green Design (non-toxic renewable elements), Integrative Design (whole systems approach), Ecological Design (collaboration between natural & built environment) to Regenerative Design (restorative & relational).

Yet even this trend and these new and more enlightened approaches to design are necessitated by our past--and still current--failure to design (and live) appropriately and sustainably within the limits of the natural environment. Thus we must now actively design towards, not only reducing our impacts, but regenerating the human/natural environmental interface and restoring the global balance that we've so fundamentally undermined.

SUPPORT INDEPENDENT SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

BuildingGreen relies on our premium members, not on advertisers. Help make our work possible.

See membership options »Balance is one of the primary elements of design, along with proportion, pattern, rhythm and harmony. Balance is an intrinsic quality of design and harmony is the external manifestation that expresses a relationship to the landscape which contains it. Good design is timeless, functional, and beautiful, ideally in its elegant simplicity. Too much architecture is an expression of the designer's ego or of an idiosyncratic aesthetic.

Archetypes

Even in our monumental phase, in which the "great" societies created near-permanent landmarks to their own values--the pyramids, the walls, the temples and cathedrals, the city-scapes--there was an intentional application of universal design principles or archetypes that were gleaned from the natural world.

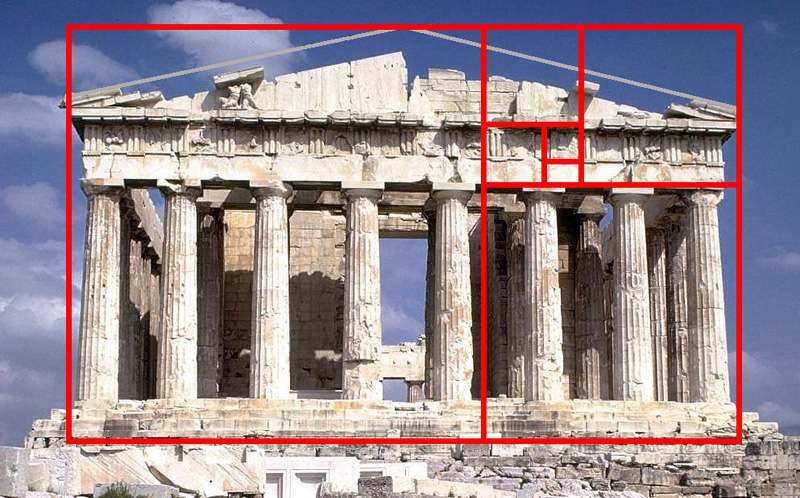

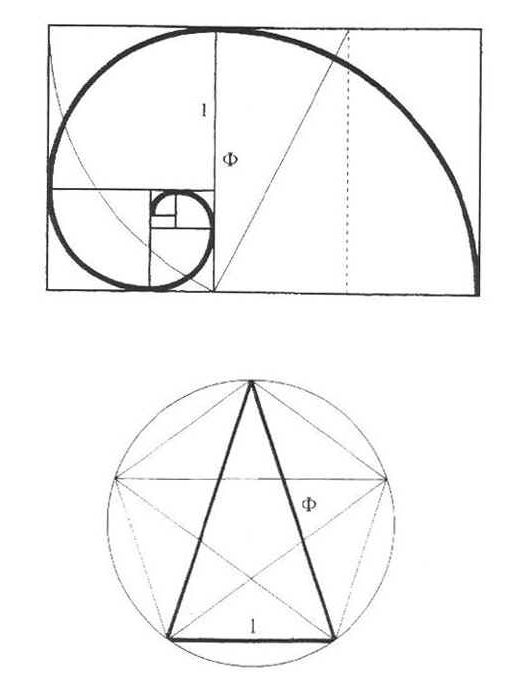

In the Western tradition, the Golden Proportion--found in everything from a fiddlehead, snail or pine cone to the swirl of a hurricane and the spiral of the galaxy--was manifest in the Great Pyramid, the Parthenon and DaVinci's Vitruvian Man (named after Roman architect and author of De Architectura, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio) and the Mona Lisa.

From the East, however, another ancient design tradition might better inform us as we move toward sustainability. Rather than the geometric perfection and permanence of the Greek tradition, Wabi-sabi is a Japanese world view and aesthetic centered on the acceptance of transience. It understands authentic beauty as imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete, and is based on the elements of asymmetry, asperity (roughness), simplicity, modesty, intimacy, and the mimicry of natural processes.

From an engineering point of view, "wabi" may be interpreted as the imperfect or unpredictable quality of any object, due to inherent material or design limitations; and "sabi" can be interpreted as the principle of imperfect reliability, or limited durability. We will return to these concepts in future essays.

These principles, however, are not unique to the East:

Would I a house for happiness erect,Nature alone should be my architect,

She'd build it more convenient than great,

And doubtless in the country choose her seat

– Horace (20 BC), author of the term "golden mean"

The essential elements of appropriate design include these: functional (form follows function), elegant in its simplicity, consistent with needs but not excess, adaptable to various life stages and occupants, buildable with available materials & skills, materials and methods appropriate for the bioregion, affordable for both occupants and the world at large.

The primary determinant of construction cost, energy use and environmental impact is size. Small houses cost more per square foot but less overall, require fewer natural resources, demand less operating expense, tend to accumulate less clutter, are easier to clean and maintain, are more intimate and reduce life to its essentials.

Principles to make small work:

- minimize circulation spaces (hallways)

- avoid diagonal circulation paths

- maintain an open floor plan

- employ multi-function spaces

- tie spaces together visually

- separate spaces without walls

- use thin interior (movable?) walls/dividers

- create niches, shelves, and built-ins

- employ views to expand small spaces

- use varying heights, colors and textures – expansive or intimate

- incorporate indoor/outdoor transition spaces

- locate windows for view, ventilation & natural light

"You know you have reached perfection of design not when you have nothing more to add, but when you have nothing more to take away." - Antoine de Saint Exupéry (author of The Little Prince)

The full 10-part series of Robert's reflections will be as follows. Tune in next week for more:

1. Context – land, community & ecology

2. Design – elegant simplicity, the Golden Mean

3. Materials – the Macrobiotics of building: natural, healthy and durable

4. Methods – criteria for appropriate technology

5. Foundations – it all starts here: how do we begin?

6. Envelope – shelter from the storm, our third skin

7. HVAC – maintaining comfort, health and homeostasis

8. Energy & Exergy – sources and sinks

9. Hygro-Thermal – the alchemy of mass & energy flow

10. Capping it All Off – hat & boots and a good sturdy coat

copyleft by Robert Riversong: may be reproduced only with attribution for non-commercial purposes

Robert Riversong has been a pioneer in super-insulated and passive solar construction, an instructor in building science and hygro-thermal engineering, a philosopher, wilderness guide and rites-of-passage facilitator. He can be reached at HouseWright (at) Ponds-Edge (dot) net. Some of his work can be seen at BuildItSolar.com (an article on his modified Larsen Truss system), GreenHomeBuilding.com (more on the Larsen Truss), GreenBuildingAdvisor.com (a case study of a Vermont home), and Transition Vermont (photos).

Published May 4, 2011 Permalink Citation

(2011, May 4). Small Can Be Beautiful – Use these principles to make it work. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/blog/small-can-be-beautiful-–-use-these-principles-make-it-work

Comments

Mike, What has changed in the

Mike,

What has changed in the human habitation of the earth is our population density. As with all predator-foragers, we had no choice but to live within the carrying capacity of the local environment or move on to another suitable ecological niche (while the last recovered) or have our own numbers reduced as we decimated our food supply.

With the invention of "profit" - in the form of sedentary agricultural surplus - our population was able to outgrow the natural carrying capacity of the land and this often led to deforestation and/or desertification. Later, with the exploitation of high-exergy fossil fuels, humanity was able to expand exponentially as well as survive and thrive in otherwise inhospitable environments.

With this latter "advance", our output of wastes drastically outpaced the earth's ability to recycle or absorb and we "purchased" our own personal and social complexity (wealth, comfort and security) at the expense of the accelerated dissipation of entropy into the environment. The result is global pollution, resource depletion and irreversible climate change - which has also initiated the sixth great extinction and the first to be caused by a single species. It has typically taken the earth 20 to 50 million years to recover from such a "perturbation".

The myth of the "noble savage", however, is far more true than imaginary. With a pre-Columbian native population in North America of between 2 and 18 million people, there remained 50 million bison as late as 1840. With the European advancement into the Western US, only 29 remained by 1910. In 1813, John Audubon estimated a billion passenger pigeons in a single migration. With farm and urban development, the last such pigeon died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. The question of which population was "noble" and which was "savage" can be answered by those examples.

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.