Blog Post

How Tight is Too Tight?

As houses get tighter, they becaome less able to 'breathe' on their own -- they need mechanical ventilation. Put another way, energy efficient houses deserve healthy indoor air.

The first question I usually get when I start talking about insulating and buttoning-up houses is, "Won't my house be too tight?" It's a very logical question.

Tight houses need fresh airAs we make houses tighter, less air flows through them. With less circulation, pollutants in the house can build up. These pollutants can include carbon dioxide from our breathing, smoke from burning our toast, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from cleaning materials and furnishings, moisture (which isn't a pollutant itself, but causes mold and other problems), and, yes, even bathroom deodorizers that often contain harmful chemicals. Without as much fresh air getting in to dilute those pollutants and replenish the oxygen we need, aren't we going to suffocate? Shouldn't the house be left leaky?

The concern is right on--that a tight house without enough fresh air is a bad thing. But the solution--to keep the house leaky--is wrong.

There are several problems with the idea of relying on a leaky building envelope to ensure adequate fresh air in a house.

Leaky houses costs you money and waste energyIn a typical house, air leakage can account for 25-40% of the total heat loss of the house. If we increase insulation levels and put in better windows but leave the house leaky, the fraction of total heat loss coming from air leakage increases. Cold air leaking in means dollars leaking out. To make matters worse, the rate of air leakage is highest when the energy impact of that leakage is the greatest--when it's very cold or very windy.

SUPPORT INDEPENDENT SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

BuildingGreen relies on our premium members, not on advertisers. Help make our work possible.

See membership options »Air leaks can cause moisture problemsWhen warm air leaks out through cracks and gaps in your building envelope during the winter, that air cools off and may reach the "dew point." This is the temperature at which water vapor (a constituent of all air) can condense into liquid water.

The dew point depends on the temperature as well as the relative humidity--the higher the relative humidity the higher the temperature at which the dew point will be reached. When condensation occurs within your walls or ceiling, stuff gets wet.

Mold can grow--potentially making you sick--and cellulosic materials like wood can rot.

You can't rely on air leaks to be reliableThe strategy of keeping your house intentionally leaky can't even be relied on to provide fresh air. Air movement through a building envelope depends not only on the envelope leakiness, but also on the "pressure differential" across the envelope. When it's windy, there's a pressure differential--on the upwind side fresh air is pushed in through those gaps in the house, and on the downwind side stale house air is sucked out. And when it's really cold outside, the "stack effect" pushes warm air out through the envelope high in the house and sucks in outside air near ground level.

The problem is that there isn't always one of these situations to create that pressure differential we need for fresh air. On a day without much wind during the spring and fall months, when it's not that much colder outside than in, the differences in pressure won't be enough to cause much air exchange--even with a quite leaky envelope, so you won't be ensuring fresh air.

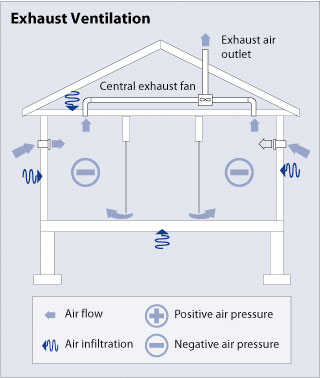

Tighter houses are better housesMy answer to the question of how tight we should make our houses is "really, really tight." But we also need to provide mechanical ventilation. With a ventilation system--which can be as simple as the continuous or intermittent operation of quiet bathroom fans with intentional air inlets, to a whole-house ventilation system--you will be sure of getting the fresh air you need. With an extremely airtight envelope and a mechanical ventilation system that controls exactly where and how much air is brought in and exhausted, you get the quantity of fresh air you need, you deliver that fresh air where it's needed, and you get it consistently, whether it's windy or not and no matter the outside temperature.

"Whole-house" ventilation is most effective because the fresh air is delivered exactly where it's intended (bedrooms and living room, for example) and stale air is exhausted from the places pollutants are most likely to be produced (typically bathrooms and kitchens).

With whole-house ventilation, you can also capture heat from the outgoing air stream and transfer it to the incoming fresh air. This is accomplished with a "heat-recovery ventilator" or "air-to-air heat exchanger." This strategy makes a great deal of sense in cold climates, such as ours, though it does increase cost.

FURTHER RESOURCES

Green Primer:Can Houses be "Too Insulated " or "Too Tight"?

Green Building Encyclopedia article:Air Leaks Waste Energy and Rot HousesVentilation Choices: Three Ways to Keep Indoor Air Clean

Blogs:Heating a Tight, Well-Insulated HouseWhat's the Most Cost-Effective Way to Bring Fresh Air into a Tight House?Tight Houses: A Good Idea (and Code Requirement)Passivhaus Homes are Extremely Tight and Energy-Efficient

Published July 20, 2009 Permalink Citation

(2009, July 20). How Tight is Too Tight?. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/news-article/how-tight-too-tight

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.