What about nuclear - seems to be the biggest category missing in the chart.

Blog Post

Energy Return on Investment

For the past few weeks, I've been writing about petroleum: what it is, the history of petroleum use, and what's ahead for this ubiquitous energy source that, to a significant extent, defines our society. This week, I'll cover a method of evaluating not only petroleum, but other energy sources as well: "energy return on investment."

Energy return on investment (EROI), sometimes referred to as "energy return on energy invested" or "net energy analysis," is the energy cost of acquiring a particular energy resource. Mathematically, it is the ratio of the amount of usable energy acquired from a particular resource to the energy expended to acquire that energy.

The higher the EROI, the more "profitable" the energy resource (from an energy standpoint). If the EROI drops below 1:1, it means that it takes more energy to produce the usable energy than is contained in the finished product.

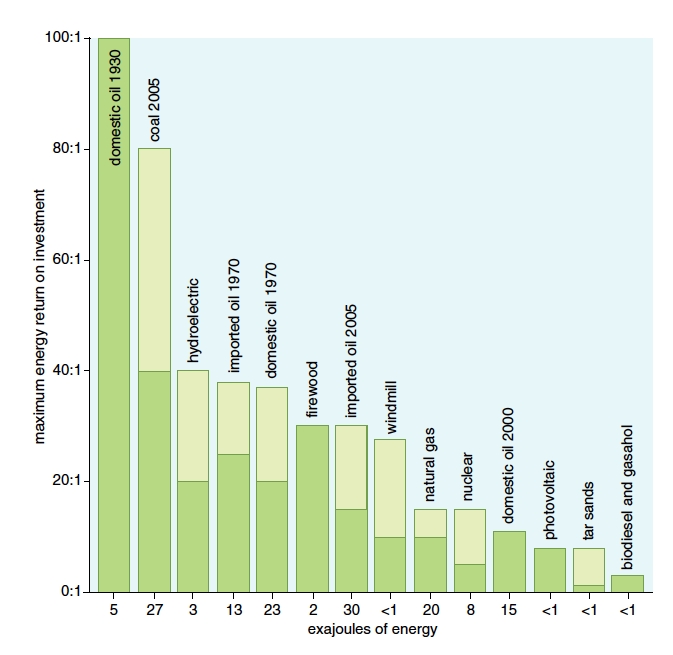

The significance of this sort of analysis becomes clear when we look at different energy sources through the lens of EROI. In a May-June 2009 article in American Scientist, professors Charles Hall of the State University of New York – Syracuse and John Day of Louisiana State University reported that in 1930 domestic oil production in the U.S. had an EROI of 100:1 (100 units of energy derived for each 1 unit of oil-equivalent expended to produce it). By 1970, with our deeper wells and greater energy expenditures for pumping and processing the oil, the EROI of domestic oil had fallen to 40:1. Today U.S. oil is produced at an EROI of about 14:1, according to Hall and Day. The EROI for Athabascan tar sands in Alberta, from which a million barrels per day of oil is now being produced, is just 6:1, according to Canadian petroleum geologist David Hughes (as quoted in the January 7, 2011 issue of The Walrus).

Approximate EROI values for some other energy sources, according to Hall and Day, include coal 80:1, hydroelectric power 40:1, firewood 30:1, wind power 28:1, natural gas and nuclear power 18:1, and photovoltaics 8:1 (see chart from American Scientist).

When we have to invest almost as much fossil fuel in an energy source as that energy source provides, we have to rethink the wisdom of investing in it. That's the case with corn-ethanol today, which--depending on whose estimates you believe--has an EROI between 0.8:1 and 1.5:1. In other words, for every one unit of fossil fuel energy invested (growing corn and converting it into ethanol) you end up with between 0.8 and 1.5 units of ethanol produced; at the worst-case estimate, we invest more energy in producing ethanol than the finished product contains. This is why a lot of experts--not only environmentalists but also economists--are questioning the wisdom of spending billions of taxpayer money each year to prop up the corn-ethanol industry.

SUPPORT INDEPENDENT SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

BuildingGreen relies on our premium members, not on advertisers. Help make our work possible.

See membership options »There are situations in which investing in energy resources with very low EROI values can make sense--for example, if most of that energy investment is front-loaded and the subsequent operating energy requirements are relatively low. This is the case with solar water heating. It takes a lot of energy to produce copper absorber plates, piping, and other solar collector components--but most of those energy inputs are "upstream" (that is, they have already been expended by the time your solar water heating system is hooked up).

It can make good economic sense for an individual--or a society--to invest in that energy producing system as long as the ongoing energy input is renewable (sunlight, wind, or wave power, for example) and as long as the system can be maintained and operated for a long time.

As we debate our future energy choices and policies, energy return on investment should be an important part of the discussion. Such analysis gives us a "reality check" as we figure out where to put our energy investments--and which energy technologies our government should subsidize. Such an analysis would likely put a stop to the pork-barrel subsidies going into corn-derived ethanol.

In addition to this Energy Solutions blog, Alex contributes to the weekly blog BuildingGreen's Product of the Week, which profiles an interesting new green building product each week. You can sign up to receive notices of these blogs by e-mail--enter your e-mail address in the upper right corner of any blog page.

Alex is founder of BuildingGreen, Inc. and executive editor of Environmental Building News. To keep up with his latest articles and musings, you can sign up for his Twitter feed.

Published January 11, 2011 Permalink Citation

(2011, January 11). Energy Return on Investment. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/news-article/energy-return-investment

Comments

I can distinctly remember bei

I can distinctly remember being at a Jaycee (Junior Chamber of Commerce) meeting in Richmond, VA back in 1993 where I had arranged for our guest speaker to be the CEO of Ethyl corporation which was headquartered there. He was talking about "corn derived fuel" being "the wave of the future for economic and environmental change."

We were all very interested in the concept and the fact that it might actually be coming from a company right in our backyard. But there where also plenty of jokes afterwards about visions of putting corn kernels into our gas tanks and then popped-corn spewing out of our exhaust pipes as we drove down the road.

It seemed like such a forward thinking concept and admirable goal at the time: Use readily renewable materials which are domestically grown to ween us off of the imported fossil fuels. And now 17 years later, it is yet another example of what happens when corporate profits supersede sound science and rational environmental approaches.

Unfortunately, I suspect that we have some very popular and widely-accepted "energy" based products in our midst now which will look similarly foolish and short sighted in 15 or 20 years time.

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.