The LEED Green Building Rating System™ has only been officially “on the street” for a month, but it is already being used informally as a framework for green design of hundreds of projects. It is officially referenced in the building guidelines of several local governments and federal agencies, and unofficially used by many more. What is this system that has generated such interest, and how does it work? Our account of LEED follows.

What LEED Is

LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. The LEED Rating System is a method for providing standardization and independent oversight to claims of environmental performance for nonresidential buildings.

LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design. The LEED Rating System is a method for providing standardization and independent oversight to claims of environmental performance for nonresidential buildings.

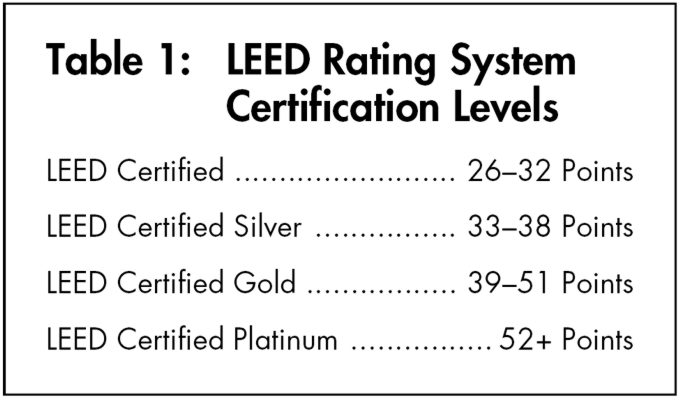

Its checklist of green performance goals and measures has 69 possible points—a building that can document compliance with 26 or more points can be LEED-certified (see Table 1).

LEED is a project of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), a nonprofit organization of architects, construction companies, product manufacturers, engineers, consultants, and many others. The Council’s stated vision is “Green buildings and communities for a healthy and prosperous planet.” Of the various initiatives and programs that have emerged from the Council since it was founded in 1993, LEED is by far the most significant in terms of the interest it has generated.

Given the enormous impact that LEED now has within the USGBC, it is not surprising that the origins of LEED go back to the beginning of the Council, and even before. According to Michael Italiano, Esq., who worked with David Gottfried to create the Council, the proposal for a green building rating system was the subject of an issue paper drafted by Gottfried at the Council’s inception. The rating system paper was one of five such papers presented to the Council at its first meeting, hosted by The American Institute of Architects in April 1993. Gottfried had championed the rating system idea even earlier, at the ASTM Green Building Subcommittee (ASTM E50.06), which he founded and chaired.

Gottfried’s interest came from a rating system that was already established in the U.K., the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method or BREEAM (see EBN Vol. 6, No. 2), and by another one under development at the time by Dr. Ray Cole at the University of British Columbia, the Building Environmental Performance Assessment Criteria (BEPAC, see EBN Vol. 3, No. 2). When work on the LEED rating system began in 1994, the Council initially considered the idea of working with BREEAM to create a U.S. version. An intern with the Council, Chris Pomeroy, was charged with reviewing BREEAM and other emerging rating systems as a starting point for Council efforts. For various reasons, those models were rejected, and Pomeroy created an initial draft of a rating system as a starting point for the Rating System Committee.

Gottfried’s interest came from a rating system that was already established in the U.K., the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method or BREEAM (see EBN Vol. 6, No. 2), and by another one under development at the time by Dr. Ray Cole at the University of British Columbia, the Building Environmental Performance Assessment Criteria (BEPAC, see EBN Vol. 3, No. 2). When work on the LEED rating system began in 1994, the Council initially considered the idea of working with BREEAM to create a U.S. version. An intern with the Council, Chris Pomeroy, was charged with reviewing BREEAM and other emerging rating systems as a starting point for Council efforts. For various reasons, those models were rejected, and Pomeroy created an initial draft of a rating system as a starting point for the Rating System Committee.

In the Spring of 1995 Rob Watson, a senior scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), took over as chair of the rating system committee. “[The subject of buildings and their environmental impact] was a vacuum in the environmental movement that wasn’t being filled by anybody,” says Watson, noting that other than NRDC there is still no mainstream environmental group active in this area. Sensing that a rating system would be a good way to influence the industry, Watson chose to devote a substantial amount of time to the project, and progress on the rating system—which got the name “LEED” in April of 1996—accelerated. Other members of that early Committee who are still active with LEED include Italiano, Sandra Mendler, AIA (now with CUH2A, Inc.), and William Reed, AIA (now with Natural Logic, Inc.).

The Committee generated several drafts for review, though little remains of any of those in the current version. “I can think of very few things that survived from those early drafts,” says Watson. Even after Version 1.0 was officially adopted by the Council, there were some lingering concerns, and the Council lacked the resources to roll out a full program. Instead, pilot projects to test the system were solicited at the Council’s August 1998 Member Meeting in Big Sky, Montana. Funding from the U.S. Department of Energy financed the administration of those pilot projects and the creation of a LEED v.1.0 Reference Guide.

Meanwhile, refinement of the system continued under the direction of Mendler and Reed, co-chairs of the LEED Technical Committee, with subcommittees actively reviewing each topic area. Lynne Barker (formerly Lynne King) and Tom Paladino were also instrumental in this process as co-chairs of the LEED Pilot Committee. In the summer of 1999 a large group of technical experts (including EBN’s Alex Wilson) convened for a weekend workshop at the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation’s Pocantico Estate in Tarrytown, New York and initiated many of the refinements now in LEED 2.0. The summer of 1999 also marked the start of Steve Keppler’s position as the Council’s first full-time LEED project manager.

The pilot testing resulted in LEED certification of its first twelve buildings on March 30, 2000 (see EBN Vol. 9, No. 4). LEED 2.0 was approved by members on May 9, 2000, though buildings that were working towards certification under LEED 1.0 will still be allowed to apply under that system. The LEED 2.0 Reference Guide is currently being developed by Paladino Consulting of Seattle and will be published exclusively on the Internet.

How LEED Certification Works

The first step in certifying a building under LEED is to register the project with the USGBC. The registration fee ($350 for Council members, $500 for non-members) gets you access to the online reference materials and up to two free “credit interpretations.” All credit interpretations will be posted with the LEED 2.0 Reference Guide on the Web, so that subsequent projects have the benefit of all prior interpretations. Interpretation requests are submitted online, and a two-week turnaround is promised. Should more than two interpretations be needed, additional requests are handled for $220 each.

Once the building is complete, the owner or designer must submit a checklist showing which credits are being claimed, along with the documentation needed for those credits and a fee of $1,200 ($1,500 for nonmembers). The certification committee then reviews the project and, if documentation is in order, awards the appropriate rating. Certified projects receive a certificate and brass plaque, along with a media kit and the promise of exposure on the Council Web site and in the trade press.

In addition to these direct costs, projects that intend to be LEED-certified will have to budget some additional time for the design and construction team to monitor and document compliance with the credits. Actual documentation requirements are still being worked out, so it is too early to estimate what these costs will be, but they will not be insignificant.

Recognizing that the LEED ratings are based on a building’s design rather than its actual operation, the Council has determined that a LEED rating will be considered valid for five years. At that time, the building will have to undergo recertification under a yet-to-be-developed LEED Operations and Maintenance Rating System to retain its rating. There will likely also be the possibility that the building’s rating might be adjusted up or down at that time, according to Watson.

The Credits

At LEED’s core is the checklist of credits that determine available points for various green measures. The entire detailed checklist is available free as the LEED Green Building Rating System™, an Adobe Acrobat™ file that can be downloaded from the USGBC’s Web site (registration is required to download the file). This 25-page document lists every available credit, describing the intent, the requirements, and some sample technologies or strategies for meeting the requirement. EBN readers with interest in LEED are strongly encouraged to get this document, as it is the only official guide to the LEED system.

At LEED’s core is the checklist of credits that determine available points for various green measures. The entire detailed checklist is available free as the LEED Green Building Rating System™, an Adobe Acrobat™ file that can be downloaded from the USGBC’s Web site (registration is required to download the file). This 25-page document lists every available credit, describing the intent, the requirements, and some sample technologies or strategies for meeting the requirement. EBN readers with interest in LEED are strongly encouraged to get this document, as it is the only official guide to the LEED system.

The overview below summarizes the credits and adds some commentary on pertinent issues or concerns. In general, the LEED document has some inconsistencies, possibly because in some areas the concepts and intent of the credits have been distilled and refined over several years, while in others new credits were added late in the process and their implementation is less than crystal clear. Many loose ends remain to be clarified in the LEED Reference Guide and worked out as the first projects work their way through this new system.

1 Prerequisite · 8 Credits · 14 PointsExperts at the Pocantico charrette made significant changes to this section to avoid situations in which it would be easier to get points with greenfield redevelopment than with redevelopment of disturbed sites. The only Prerequisite requires that an erosion and sediment control plan be followed that conforms to EPA’s best management practices for stormwater control or local standards (whichever is more stringent).

Credit 1 – Site Selection provides one point for avoiding development of an inappropriate site—for example, agricultural land, flood zones, or land with wetlands or critical habitat.

Credit 2 – Urban Redevelopment provides one point for carrying out the development in a high-density or urban area rather than developing a greenfield site.

Credit 3 – Brownfield Redevelopment provides one point for carrying out the development on a brownfield, which is a site adversely affected by real or perceived environmental contamination. As with Credit 2, this reduces development pressure on greenfield sites and can help to protect open space.

Credit 4 – Alternative Transportation provides up to four points for measures that reduce dependence on private automobiles—a notable commitment for a rating system on buildings. One credit is provided for each of the following: a) building near a light-rail station or bus lines; b) providing bicycle storage and shower facilities to encourage bicycle commuting; c) installing alternative refueling stations; and d) providing preferred parking for carpool and vanpool vehicles, while also minimizing overall parking.

Credit 5 – Reduced Site Disturbance provides one or two credits for measures that conserve existing natural areas and restore damaged areas. One credit is provided a) with greenfield sites if development is done so as to severely restrict impacts beyond the immediate building(s) and roadways, or b) with previously developed sites if a minimum of 50% of the remaining open area is restored with native plantings. A second credit is provided if the open space left after development exceeds the local zoning’s open space requirements by at least 25% (the development footprint includes buildings and roadways/parking).

Credit 6 – Stormwater Management provides one or two credits for implementing a responsible stormwater management plan. One credit is provided when there is no net increase in stormwater runoff after development or—for sites in which at least half of the land area is already covered with impervious surfaces— where a 25% reduction in stormwater runoff can be achieved. A second credit is awarded for stormwater treatment that removes 80% of the post-development total suspended solids (TSS) and 40% of the post-development total phosphorous, as outlined in EPA standards.

Credit 7 – Landscape and Exterior Design to Reduce Heat Islands awards one or two points for measures reducing the localized warming referred to as the “urban heat island” effect. One credit is provided for use of prescribed shading strategies and reflective materials for non-roof impervious surfaces (e.g., parking lots). A second credit is provided if a green roof (vegetated) is used for at least 50% of the roof area, or if roofing on at least 75% of roof surfaces is reflective to Energy Star standards and has high-emissivity. (The LEED document incorrectly states “low-emissivity” and doesn’t specify a threshold.) Even though it is not addressed in the Energy Star program, high-emissivity of the roof surface is important because, to stay cool, a roof must not only reflect most of the radiation that it receives, but it must also be able to emit radiation to release the heat it absorbs. Galvanized steel is the material most affected by this distinction: it is reflective but still heats up due to its low-emissivity.

Credit 8 – Light Pollution Reduction provides one credit for keeping outdoor lighting levels low (as defined by recently established lighting industry recommendations for exterior lighting) and avoiding all light trespass from the site. This credit was added during the 1999 experts charrette.

Water Efficiency

0 Prerequisites · 3 Credits · 5 PointsRelative to its global significance as a resource, water has surprisingly little influence in the LEED system. Unlike some other rating systems, LEED does not require that a minimum number of points come from each section. As a result, with only five points total and no prerequisites in the water section, it is entirely possible that a building could be LEED-certified—even at the Platinum level—yet have no water-conservation features beyond what is required by law.

The three water credits apply to landscaping, wastewater, and indoor water use, respectively. All three water credits are based on use reductions from a certain baseline level. For indoor water use, the baseline is determined by calculating estimated usage assuming Energy Policy Act-compliant fixtures. For the other two credits the calculation method is not specified, and users are referred to the Reference Guide.

Credit 1 – Water-Efficient Landscaping provides one point for a 50% reduction from the baseline in potable water use and a second point for an additional 50% reduction, meaning no potable water use. The reduction can be achieved with efficient irrigation technology or by irrigating with captured rainwater or recycled graywater.

Credit 2 – Innovative Wastewater Technologies offers one point for either reducing sewage flow by 50% from the baseline or treating all wastewater on site to tertiary standards.

Credit 3 – Water Use Reduction applies to all non-landscaping uses, including both sanitary fixtures and HVAC equipment such as cooling towers. One point is achieved with a 20% reduction from the baseline, and a second point for an additional 10% reduction.

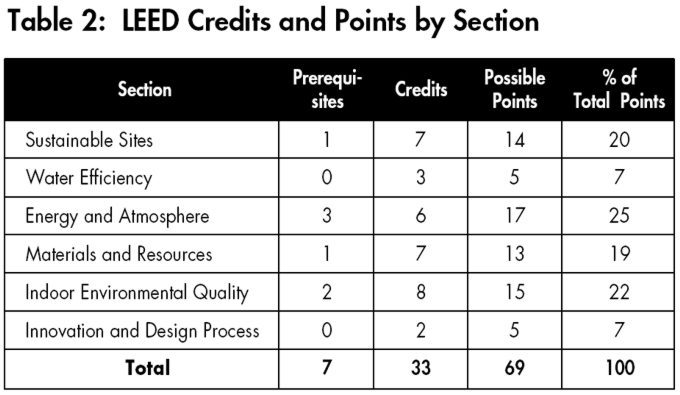

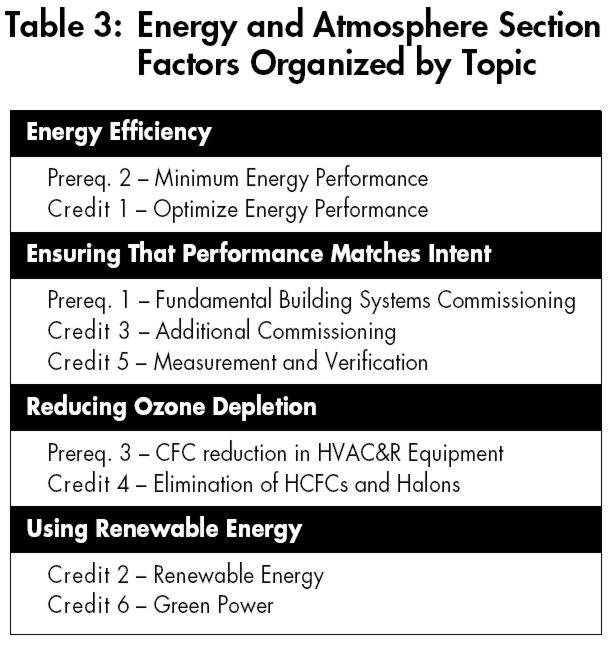

3 Prerequisites · 6 Credits · 17 PointsAppropriately, LEED places a large emphasis on energy. Of the 17 points in this section, 15 relate to energy efficiency or renewable energy (see Table 3).

3 Prerequisites · 6 Credits · 17 PointsAppropriately, LEED places a large emphasis on energy. Of the 17 points in this section, 15 relate to energy efficiency or renewable energy (see Table 3).

In addition, the four points in Site Credit 4 on alternative transportation also promote energy conservation. Just how feasible it will be to earn such a large number of energy credits, however, depends on the details of energy performance calculations, which are yet to be worked out (see sidebar, page 12). A significant shift from LEED 1.0 is that several credits outlining prescriptive measures to reduce energy use have been omitted, since they provide benefits that should be captured by this performance credit.

Prerequisite 1 – Fundamental Building Systems Commissioning requires that a commissioning authority be identified and contracted to perform certain tasks. Making this role a prerequisite is a strong endorsement by LEED of the emerging practice of commissioning.

Prerequisite 2 – Minimum Energy Performance requires a level of energy efficiency as described in Standard 90.1–1999 from the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).

–(See sidebar for details on this requirement.)

Prerequisite 3 – CFC Reduction in HVAC&R Equipment bans the use of CFC-based systems in new buildings and requires a phaseout plan in existing buildings. The former is already law in most developed countries but was retained here because LEED may also be applied in countries without such laws.

Credit 1 – Optimize Energy Performance offers from two to ten points, depending on the level of energy savings from the ASHRAE 90.1 baseline. The range of energy savings to get these points is 20% to 60% for new buildings and 10% to 50% for renovations (see sidebar).

Credit 2 – Renewable Energy offers one to three points for the use of renewable energy generated on-site to meet 5% to 20% of the building’s energy needs. Energy from these sources cannot be used to reduce the building’s energy use as calculated for Credit 1, and strategies that are used to reduce a building’s energy load, such as passive solar and daylighting, cannot be included under Credit 2.

Credit 3 – Additional Commissioning offers a point for an expanded commissioning role beyond that of Prerequisite 1.

Credit 4 – Elimination of HCFCs and Halons provides one point if HVAC and fire-suppression equipment do not use HCFCs or Halons. The inclusion of HCFCs in this credit, even though their ozone-depletion potential is tiny compared with Halons, has been the subject of some public controversy. This is a loaded issue in part because it creates a distinct preference for chillers from Carrier, which has moved away from HCFCs, over those from competitors, in spite of reasonable arguments that more efficient HCFC-based chillers may be a better overall environmental choice. The LEED Committee has stuck with this requirement, arguing that energy efficiency benefits are accounted for in Credit 1, and it is important to take a strong stand against ozone depletion.

Credit 5 – Measurement and Verification provides a point for the installation of equipment for continuous metering of energy and water use, as described in the U.S. DOE’s International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol.

Credit 6 – Green Power offers a point if the facility enters into a two-year contract to purchase power from an independently certified green electricity provider.

Materials and Resources

1 Prerequisite · 7 Credits · 13 PointsThe Materials and Resources Prerequisite requires that the building accommodate recycling of solid waste by occupants.

Credit 1 – Building Reuse offers up to three points for reuse of an existing facility—one point for reusing at least 75% of the structure and shell, two points for reusing 100%, and a third point for also reusing 50% of interior finishes. Credits are not awarded for reuse of glazings or window assemblies on the exterior shell because, in many cases, reusing old glazing is not good for energy performance or comfort.

Credit 2 – Construction and Waste Management offers one point for recycling at least 50% (by weight) of construction, demolition, and land-clearing waste, and a second point for recycling another 25%. Source reduction on the job site is identified as an appropriate strategy, but details on how such reductions would be determined are left for the Reference Guide.

The remaining credits, #3 through #7, all address the use of environmentally preferable materials. During the development of this section it was generally acknowledged that, ideally, all materials would be chosen based on reliable and comprehensive life-cycle assessments. Since neither the assessments nor a tool for their use is available, several indicators of environmental preferability were identified instead. These are spelled out in each of the credits.

Credit 3 – Resource Reuse provides one point for using salvaged or refurbished materials for at least 5% of the materials on the project, and two points for 10%. After much debate, the Committee chose to base these percentages on the cost of the materials (as opposed to their volume or weight). However, since some salvaged materials may have little or no cost, yet require a lot of labor to use, there is the provision that the value of the materials they replace can be used to calculate their “cost.”

The method for calculating the percentages for this and the following three credits was subject to revisions even after the ballot version of LEED 2.0. The final version stipulates that the cost of the salvaged materials be divided by the cost of all building materials in the project, excluding mechanical and electrical systems. Also excluded are all labor costs and project overhead and fees. While this method represents a reasonable resolution to a complex problem, it assumes that no components of the mechanical or electrical systems will be salvaged (or qualify under the other credits that use this method). Whether and how such products might be included in the calculation is another sticky issue for the Reference Guide to resolve.

Credit 4 – Recycled Content provides one point for the use of at least 25% of building materials with recycled content, and a second point for using at least 50%. The materials used to qualify for this credit must have a weighted average (average that factors in the quantity of each material) of at least 20% post-consumer recycled content or 40% post-industrial.

Credit 5 – Local/Regional Materials provides points for the use of materials sourced and manufactured within a 500-mile (800 km) radius of the building site.

Credit 5 – Local/Regional Materials provides points for the use of materials sourced and manufactured within a 500-mile (800 km) radius of the building site.

The first point is based on using 20% of materials that are manufactured within this radius, and the second point is achieved if at least half of this 20% is made with raw materials that are also from within this radius. This credit has the potential to drive whole new labeling systems within the building materials industry because many manufacturers have multiple factories and it is not often possible for a contractor or tradesperson to know which plant is the source of any particular shipment.

Credit 6 – Rapidly Renewable Materials offers a point for the use of at least 5% of materials that are made from resources such as agricultural products or bamboo. Clarification added between the ballot and final versions of LEED 2.0 stipulates that the materials in question must not contribute to biodiversity loss, erosion, or air pollution; credit interpretations will likely be needed to rule on the acceptability of various specific materials.

Credit 7 – Certified Wood provides a point when at least 50% of all wood-based materials in a project are certified to Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) guidelines. Unlike the four previous credits, this one is not based on any calculation of all materials in the building, but just those made of wood. Changes to the FSC labeling policy (see page 3) will make this point easier to achieve than the Committee may have originally intended—an issue that will no doubt be reviewed when LEED is updated in 2003. In any case, the reference of FSC guidelines is an important endorsement of that system.

Indoor Environmental Quality

2 Prerequisites · 8 Credits · 15 PointsPrerequisite 1 – Minimum IAQ Performance requires compliance with ASHRAE’s Standard 62–1999 on ventilation for IAQ.

Prerequisite 2 – Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) Control bans exposure of occupants to ETS, either with a general smoking ban, or with restricted smoking rooms to effectively remove ETS from the building.

Credit 1 – Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Monitoring offers a point for installation of a permanent CO2 monitoring system and setting it to control CO2 levels so that indoor levels do not exceed outdoor levels by more than 530 parts per million.

Credit 2 – Increase Ventilation Effectiveness provides a point for air distribution systems that promote effective air exchange. Displacement ventilation systems (using underfloor distribution and overhead exhaust), low-velocity laminar-flow ventilation, and natural ventilation (with documentation of effective inlet and outlet design) are suggested approaches.

Credit 3 – Construction IAQ Management Plan provides one point for conformance to a range of measures designed to prevent indoor contamination that results from construction processes. A second point is available for either a two-week flush-out period after construction and prior to occupancy, or performing a baseline IAQ test using procedures developed for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Research Triangle Park Campus.

Credit 4 – Low-Emitting Materials provides one point for meeting volatile organic compound (VOC) emission limits in each of four product areas: adhesives and sealants—referencing limits set by two air quality agencies in California; paints and coatings—referencing a Standard from the nonprofit organization Green Seal; carpet systems—referencing a testing protocol from the Carpet and Rug Institute (CRI); and wood or agrifiber products—for avoiding products made with urea formaldehyde binders. Of these, the carpet category should be an especially easy point, as nearly all carpets and carpet adhesives comply with the CRI labeling program.

Credit 5 – Indoor Chemical and Pollutant Source Control offers one point for a) providing effective grills and walk-off mats at entries to prevent soiling of floor surfaces, and b) isolating areas in the building where hazardous chemicals are handled.

Credit 6 – Controllability of Systems provides one point where occupants located near the perimeter have access to operable windows and localized lighting controls, and a second point if half the occupants who are not near the perimeter have individual comfort controls. By separating the requirements according to perimeter and non-perimeter spaces, this credit strongly encourages operable windows and individualized controls without going as far as promoting European-style finger-plan designs that put all occupants near windows.

Credit 7 – Thermal Comfort offers two points, one for complying with ASHRAE Standard 55–1992 on thermal comfort, and a second for installing a permanent automated control system for temperature and humidity. ASHRAE Standard 55 defines comfort conditions based on air temperature, mean radiant temperature, humidity, and air movement. While it includes all these parameters, the comfort zone it defines is narrow enough that no building in the U.S. that relies purely on natural ventilation for cooling can be expected to comply. The humidity control requirements of the second point also exclude naturally ventilated buildings.

Credit 8 – Daylight and Views offers a point for daylighting and another for access to views (or at least to vision glass, regardless of what is seen outside). The daylight point requires the provision of a significant amount of daylight in at least 75% of the regularly occupied space. The view point demands a direct line of sight to vision glass from 90% of such spaces. Unlike Credit 6, these points do encourage narrow plan buildings.

0 Prerequisites · 2 Credits · 5 PointsThe Innovation and Design Process section offers four possible points for green measures not found in the checklist. These open points help counteract the drawbacks of relying on a checklist for rating a building because they allow designers to claim points for green strategies that are not included in the LEED checklist. Each such point will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis by the LEED Committee.

This section also offers one point for use of a “LEED-Accredited Professional” as a principal participant on the project team. Building professionals will be accredited, beginning in the fall of 2000, based on a proctored exam that will test knowledge of green building in general and the LEED system in particular. One-day LEED training workshops that are being held in various cities should be adequate preparation for most practitioners to pass the test, according to Paladino, one of the instructors. “One of our primary goals with the accreditation process is to sharpen up the folks who will be handing in the certification applications,” notes Paladino, adding: “The Council’s administration costs for reviewing a poorly put together application are extremely high.”

Looking Ahead and Looking Back

The Council has committed to a three-year cycle for revisions to the LEED Rating System, so the review process will begin again soon. Meanwhile, the success of LEED has spurred members to create complementary programs for projects not covered by LEED. LEED Interiors, now in its second draft, is being developed by a Committee chaired by interior designer Penny Bonda of Burt Hill Kosar Rittelmann’s Washington, D.C. office. Formulation of LEED Residential is just beginning with a large committee under the leadership of Marc Richmond-Powers of the Austin, Texas Green Building Program. And LEED for Operations and Management has not yet been initiated in any official way, but the Council is aware that it will be needed by 2005 to provide ongoing certification of existing buildings.

Meanwhile, other organizations are building on the LEED system as they reference it for their own purposes. For example, the City of Seattle has established a policy that all municipal buildings must meet the LEED Silver rating. In addition, the City has its own guidelines about how some of the credits are to be calculated and is requiring that certain credits be achieved (in effect, adding more prerequisites).

So how good is LEED? The market has spoken, and the enormous interest expressed suggests that LEED is good enough for many people excited about the potential of an independent rating for their buildings. While the system has weaknesses, they are inevitable in a new venture of this sort; by getting the system into circulation, these weaknesses can be resolved and LEED can be made more robust. LEED 2.0 as currently published is really just the framework for a Rating System—it will become a full system once the Committee, through the Reference Guide and early users, has fleshed out the details of how a project is measured and documented for each credit. The relatively short, three-year revision cycle will encourage quick evolution.

While LEED has great potential to move the building industry toward greener practice, a rating system cannot do everything. There are some inherent problems with any system that encourages a design-by-checklist approach. For example, once a designer or team has determined that they will not be able to achieve a certain credit, the system provides no incentive to at least do what they can in that direction. Similarly, once the threshold for a credit is met, there is no incentive to try to do even better.

As checklists go, however, LEED is remarkably sophisticated, having benefited from countless hours of work (mostly volunteer) from leading green architects, engineers, contractors, and other professionals. Inclusion of the innovation credits option, while adding more work for application reviewers, greatly enhances the flexibility of the system. The cost of certification and the time required to prepare an application will be a barrier for some—as a result, for every project that gets certified, there will likely be many others just using the system internally. Either way, the Council’s mission of promoting green buildings will have been advanced, and meaningful criteria for energy- and resource-efficiency fully detailed. If the Committee continues to work out the implementation details with the same level of energy and attention that went into LEED 2.0, we will see many more green buildings.

– Nadav Malin

For more information:

Download the official LEED 2.0 document from the U.S Green Building Council: www.leedbuilding.org. Registration is required. Council members can also download additional documents about the LEED development process.

Steve Keppler, Program Manager

LEED Rating System

25 Eton Overlook

Rockville, MD 20850

301/315-6656, 425/977-8115 (fax)

skep@usgbc.org

www.leedbuilding.org