If you’ve ever held a Styrofoam cup comfortably in your hand, only to scorch your tongue sipping the piping-hot coffee inside, you know that plastic foam is a really good insulator. It’s also lightweight, generally impervious to moisture, relatively cheap, and strong.

If you’ve ever held a Styrofoam cup comfortably in your hand, only to scorch your tongue sipping the piping-hot coffee inside, you know that plastic foam is a really good insulator. It’s also lightweight, generally impervious to moisture, relatively cheap, and strong.

With all that in its favor, it would take some effort to find a contemporary, high-performance building that doesn’t incorporate foam insulation into key parts of its assembly. But a dark side to foam has come into focus over the last decade. To name a few issues, its manufacturing process can be polluting, its global warming impact can be stratospheric, it is laden with toxic flame retardants, and it is highly flammable, even with those chemical additives.

While there are moves outside the industry as well as within it to clean up foam, some projects aren’t waiting for that: they’re designing and building without foam wherever possible, looking to mineral wool, cellulose, cellular glass, cork, aerogel, and other products to provide high performance with what they perceive to be fewer environmental and health tradeoffs. After talking with numerousprofessionals who have worked to avoid foam insulation, here are the war stories that we heard, along with our research on cutting-edge insulation materials.

Industry Resistance

With the 2013 defeat of a code proposal that might have helped reduce the toxic burden of foam insulation, there is clearly resistance to change within the plastics industry. On the other hand, numerous designers and builders who are riding an industry wave of transparency and safer chemistry are working hard to avoid foam.

Larry Strain, FAIA, of Siegel and Strain Architects, has been active in a coalition dubbed Safer Insulation since the flame retardant issue came into focus. “Even before the flame retardants came up, I didn’t like it, with the life cycle and the other toxic chemicals, and what happens when it burns,” he says. “Unfortunately,” he adds, “foam works so well for what it does that it’s really hard to replace it. We’re still using it, which is why we are in the fight to make it better.”

Mara Baum, AIA, healthcare sustainable design leader at HOK, says that there are a number of project-specific issues that can either support or derail a push to avoid foam. “A project where we might consider this is also targeting net-zero energy and has a tight budget, so it’s a ‘nice to have,’ and it slides down in importance,” she says. Also working against the issue: “It’s not contributing to LEED Platinum, which is another goal that some projects would have. It’s an issue external to LEED and energy—or in conflict with energy.”

One project where Baum has had traction in removing foam is a healthcare facility with aggressive health goals. That team is trying to achieve two LEED pilot credits related to avoiding chemicals of concern, which raised the issue of flame retardants in foam insulation. “We’ve been able to replace nearly all of the insulation in the walls and the roof with mineral wool,” she says, although “we haven’t been able to do that under the slab,” where conventional foam will be used. Mineral wool has lower R-value per inch than foam, but Baum says that in a healthcare facility, where thermal performance is driven by internal loads, compromising on R-value isn’t so crazy. “The R-value of the walls has relatively little impact once you reach a minimum,” she says, noting that she wouldn’t say the same thing about envelope-dominated buildings like homes.

“We’ve had more challenges than successes” in replacing foam, says Mike Stopka, AIA, now of MIST Environment, about his work at Solomon Cordwell Buenz (SCB) Architecture. Working on high-rise residential urban infill projects with a high percentage of glass and spandrels, Stopka says, “Every square inch counts, so we get pushed into designing wall assemblies with really efficient R-values and not a lot of space.”

Building scientist John Straube, Ph.D., P.Eng., of RDH Building Science, is supportive of foam substitutes—but a little perplexed at the sudden enthusiasm for them. “I think it’s overdue that people consider rock wool as a viable alternative,” he says, arguing that it was validated as a solution as far back as the 1950s in Europe, “but I think it’s been overdone.” Referring to criticism of foam, “People are so quick to jump all over something that has worked quite well.” He added, “I would just like a more reasonable discussion.”

The Devil Is in the Details

Straube is quick to point out numerous applications where foam alternatives like mineral wool can make sense:

• UV-resistant insulation is a great option in some commercial cladding assemblies where sunlight penetrates voids, according to Straube.

• If non-combustible insulation is a priority, then foam is a bad choice (even laden with flame retardants, it burns relatively easily) and mineral wool a good one. Straube says that this need is overemphasized by some mineral wool aficianados, arguing there hasn’t been a rash of fires in which exterior foam has been implicated. But, he says, if it’s important, then mineral wool is “an easy answer.”

• Referring to foam’s susceptibility to insect damage, Straube says, “If you want insulation that won’t be eaten by critters of six legs or more, [rock wool] is a great option.”

On the other hand, he also notes places where people should be more conscious with mineral wool:

• “There are places where we need higher strength,” he says. “If I want to drive a forklift over my warehouse floor, I’m not sure that rock wool is the most economic solution.”

• Straube is cautious about assemblies that might generate inward solar vapor drive. If brick cladding or another absorbent material is wetted by rain and then exposed to sunlight, water vapor can be driven inward through a wall assembly. Vapor-impermeable foam insulation is effective at stopping this, but foam alternatives like mineral wool can be vapor-permeable. “We’re working with [mineral wool manufacturer] Roxul to see where that could be a problem,” says Straube.

To fur or not to fur?

Detailing continuous exterior insulation is the sticking point for Larry Strain. Strain has worked to use mineral wool boardstock in place of rigid foam as a continuous insulation layer on his recent designs, all in the San Francisco Bay area in California and generally on public, wood-framed, one- or two-story buildings smaller than 10,000 ft2.

It takes a thicker layer of mineral wool to achieve the same R-value that one can get from a thinner layer of foam. Foam also offers a more rigid surface and more compressive strength than mineral wool. That makes for a delicate balance: Strain wants to add enough mineral wool to get necessary R-value but doesn’t want to add so much that furring becomes necessary for holding the insulation in place and attaching the cladding.

For mineral wool to be cost-competitive with foam, Strain says that he has to avoid furring—and he can avoid furring if he can avoid metal framing. “With wood framing, you can get way with 1-½" to 3" of mineral wool and not use furring,” he says, “and then it's slightly more expensive but still competitive.” If it becomes necessary to add furring, Strain says, “It’s probably adding a buck or two per square foot to the wall; that’s minor for the job, but when you’re doing a tight-budget job, they’ll say, ‘Well, we don’t need that exterior insulation.’” Exterior insulation, once seen only on high-performing jobs, is becoming standard on all projects as designers and builders have realized that even wood-framed buildings don’t deliver close to the nominal value of cavity insulation without a thermal break. Strain says that he didn’t typically include exterior insulation on buildings, except for metal ones, until a couple years ago, and since 2014 California’s Title 24 requires continuous exterior insulation.

Strain says that newer, high-density mineral wool products are more compatible with installing cladding directly over them—like foam—and have helped reduce the need for furring (see below). He pushes contractors to let him leave out that detail whenever possible, but he says it’s not a settled issue, with some experts saying that furring isn’t needed on thicker mineral wool layers, but “You take this to your contractor, and he says, ‘I don’t care [what the experts say]—I’m building it.’” Strain says that more mockups by testing labs or other reputable organizations could help set best practices and win over skeptical contractors.

“We have a project now with a high-quality finish carpenter doing the siding,” he says. “He wants to do furring, but we’re talking about doing a mockup to see if we can not do it.” There are two issues to work out: structurally, do the screws support the siding through a thick layer of mineral wool, and how much does the siding move as it’s being attached. Another issue is the weight of mineral wool: at two or three times the weight of foam for the same R-value, it’s harder to work with.

In some ways, Strain’s experience is transitional as design practices evolve. Thicker insulation, as well as use of ventilated exterior wall assemblies, have simply become more common, argues Straube, leveling the playing field between foam and mineral wool. “Once we’re talking about real insulation levels, like 3 or 4 or 5 inches,” he says, “you’re doing furring strips. And if you’re in a climate zone that gets into any kind of rain, you’re doing furring strips as well because you’re trying to protect the cladding.” Straube says that Strain’s work in the relatively mild California climate will start to have more in common with work in harsher climates where thick exterior insulation and furring strips are already seen more often. And in those applications, there is a much more level playing field between foam and mineral wool because everyone has to fur.

Windows are the real issue

According to Straube, the real issue with continuous exterior insulation is the windows—not only residentially, where debates rage over “innie” or “outie” windows in walls with deep insulation, but even more so on commercial projects. With a few inches of exterior insulation and then a gap for the rainscreen, what’s a designer to do to fill that detail? Some solutions favor putting the window all the way to the inside or the outside, but Straube points out that the architect might want the window in a certain spot for design reasons.

Using mineral wool might increase the thickness of the insulation by 10%, says Straube, but the problem is common to foam and other assemblies. Solutions include fiberglass angles or plywood boxes, but both have fire-safety issues. “One of the biggest obstacles is not that we can’t come up with solutions; it’s that the window manufacturers are completely unaware of the issue,” he claims.

Rainscreen assemblies

“We’ve basically switched our master specs to mineral wool for cavity and rainscreen walls,” says Mike Manzi, R.A., specifications manager at Bora Architects in Portland, Oregon. “Originally it was just about wanting more vapor permeability in the assembly so the wall can dry in both directions,” he says, and mineral wool is vapor-permeable, while rigid foam is fairly impermeable. At about the same time, Manzi says that the firm learned about the issues of chemical content in foam and the problems of flammability and flame propagation. “We realized that mineral wool is a win-win in all of those categories,” he told BuildingGreen.

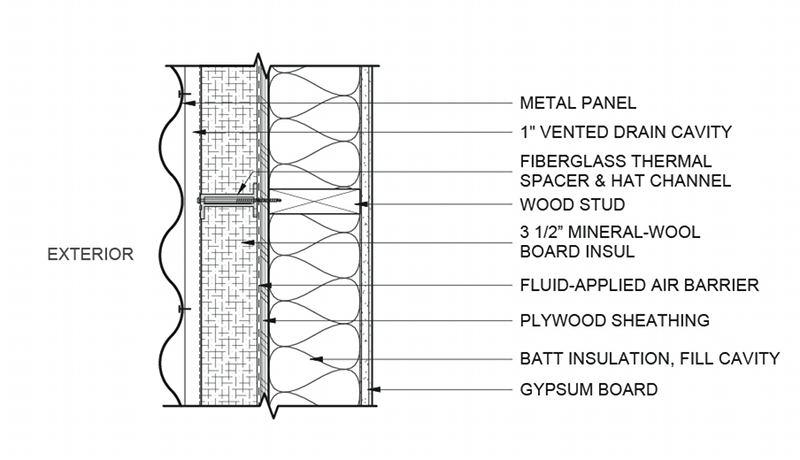

At the time, Bora was in transition from relying on cavity insulation to having continuous insulation outside the sheathing, ahead of Oregon’s adoption of an international energy code requiring that. Bora now uses details with 2-½" or more of exterior insulation, coupled with cavity insulation, and more recently has been using 3-½" of exterior insulation.

Bora specializes in higher education, K–12 schools, and cultural projects as well as high-rise residential. “Cost hasn’t come up as a big issue yet,” says Manzi, although “a lot of stuff is still in design.” He says that on a project in Indiana, there were proposals to substitute extruded polystyrene for mineral wool, and the project is sticking with mineral wool. “I don’t think there was necessarily a cost savings, maybe just the local polystyrene provider was wanting to get in on the job. It was a little bit new to them to think about using mineral wool, even though [mineral wool manufacturer] Thermafiber is in Indiana.”

According to Manzi, Bora has been successful in using mineral wool in exterior insulation with specialized fiberglass clips to avoid thermal bridging, marketed as the Cascadia Clip. The clip holds out the Z-furring and can work either horizontally or vertically, and Bora has used it both ways, according to Manzi. “It’s become our go-to for non-masonry claddings, including metal panels, rainscreen assemblies, and stucco. Typically, a metal skin system would have been done with Z-furring back to the framing, supporting the metal panel,” but that creates a significant thermal bridge from the framing out through the panel, he said. The Cascadia Clip acts like a large washer on long screws, significantly reducing that bridging.

Straube likes the Cascadia Clip for moisture resistance and as a thermal break, but he claims that some fire-safety officials worry about what happens if the clip fails and cladding starts falling off—although a fire would have to be pretty far along for that to be an issue. However, for that and other reasons, Straube likes using 1/16"-thick stainless steel clips, which he says are a fraction as conductive as regular steel, and while more conductive than fiberglass, the thickness of fiberglass offsets that benefit. “I’ve done three-dimensional heat-flow models and not seen a lot of difference,” he says—if the steel clips are detailed carefully.

Mara Baum says that when avoiding foam, her design team tried to compensate for reduced R-value by focusing on continuous insulation. The team is working with a building enclosure commissioning agent to review design details and provide recommendations for interrupting thermal bridges and closing small gaps in insulation. “My intuition is that fixing some of these problems will ultimately be more effective than adding extra inches of insulation beyond a certain point,” she says. Baum notes that “we have a rainscreen system, and mineral wool works well with rainscreens; it’s a nice fit.”

Duane Carter at SCB agrees that rainscreen assemblies are a good fit for mineral wool, with masonry cladding being more difficult. “We start to add cost with masonry ties,” he explains. With increased thickness of mineral wool, “if that gap between the support and the masonry grows over four inches, the masonry ties get more expensive. That’s when we start looking at foam board products.”

Raise the roof

Rigid foam insulation is commonly used in low-slope roofing, but some projects are switching to mineral wool. “The main challenge is that it has a lower R-value per inch, so you need more of it,” says Baum. However, Baum says that the HOK healthcare project, which includes a vegetated roof, is using a mineral wool board insulation with compressive strength equal to that of foam, addressing the main challenge in roofs. “The other challenge is that it doesn’t have all the same properties that we’re used to, so we have to detail and design a little differently.”

Mineral wool in roofs is a good fit, says Straube, noting its durability and strength. Straube also recommends considering foamed concrete. With R-value ranging from 0.86–1.8 per inch, insulating cast-in-place concrete products don’t provide sufficient R-value on their own, but for concrete, those values aren’t bad and can offer other benefits as part of a package. Typically installed with expanded polystyrene (EPS) underneath and a membrane on top, foamed concrete can add R-value while providing good roof drainage and lengthening the lifespan of the entire roof assembly, including the foam.

Under the slab

Even projects with aggressive health goals can get hung up on replacing foam under the slab. While cognizant of the life-cycle impacts of foam, including the impacts of chemical production and end-of-life disposal, Baum says, “Under the slab is not going to have the same kind of health impact. It’s pretty clear that there’s not going to be a major impact during building occupancy or if there is a fire.” She points out that “it’s also the hardest to fix if there’s an issue.” If the slab suffered from faulty engineering or installation, “We might be having problems and not knowing the cause,” she says. Better, then, to be more conservative in such an application and to try to get the objectionable flame-retardant chemicals out of the insulation, as the Safer Insulation group has argued should be allowed by code in below-grade applications. Baum’s healthcare project is using extruded polystyrene (XPS) under the slab.

Straube is somewhat cautious about replacing foam under the slab but sees potential for it. “I would like to do some longer-term tests,” he says, “but on the surface there seem to be no limitations for typical residential, light-loaded slabs.” Mineral wool is a viable option here, as well as more-expensive cellular glass. Insect resistance is one of several reasons that BuildingGreen founding editor Alex Wilson chose Foamglas for sub-slab installation on his deep energy retrofit in southern Vermont. Straube singles out polystyrene as the insulation of choice for high-load situations as well as for applications with groundwater contacting the insulation, but, cost aside, Foamglas can go toe-to-toe on both counts.

Cavity and wall insulation

Foam has never been a dominant material for insulating wall or ceiling cavities, so it’s no surprise that project teams find they have lots of options here. Blown, dense-packed, or sprayed cellulose and fiberglass are common options that perform well and avoid the toxicity issues of foam, and although batt insulation doesn’t perform as well as a spray-applied product, there are plenty of batt products to choose from, including fiberglass, mineral wool, sheep’s wool, cotton, and polyester.

Spray polyurethane foam (SPF) is the most competitive foam product in this area, and while it is used with some frequency as cavity insulation in small residential projects, it’s not cheap. Carter confirms that for large residential projects, “we don’t use it very often; it’s perceived as being too expensive.”

For retrofits or for insulating uneven masonry walls, it’s another story, though. “If we’re working on retrofitting a brick wall,” says Stopka, “and we want to insulate it from the inside,” which is common for maintaining the character of masonry buildings, Stopka says that he might choose to “spray SPF against the interior side of the brick and and fur out in-board of that with metal studs and drywall,” filling the cavity with SPF. “That can cover imperfections in the brick wall, and it can serve as a vapor retarder and air barrier.” While Stopka is hardly enthusiastic about using foam in that application for environmental reasons, “That’s the one application where it’s so much better than anything else.”

Residential retrofit

Even as gray-green mineral wool has become a more common sight on commercial projects, pink, blue, and foil-faced foam seem to continue to carry the day on residential projects, including retrofits. But wall assembly issues on a deep energy retrofit of a two-bedroom home on Lowell, Massachusetts, pushed Mark Yanowitz of Verdeco Designs toward exterior mineral wool.

Owner Chris Gleba had done extensive interior upgrades and retrofits over the years, and all that investment on the interior meant that a major insulation upgrade to the 2x4-framed, fiberglass-batt insulated home, would have to take place on the exterior. There was also a key limiting factor of a polyethylene vapor retarder that Gleba had installed behind the drywall as he had remodeled each room over the years. Installing a typical vapor-retarding foam product on the exterior would have potentially trapped moisture inside the wall, so Yanowitz recommended mineral wool.

While the building science case for mineral wool on the project was strong, Yanowitz told BuildingGreen, “my client was really into the fire-resistant qualities of it. He had seen one of his neighbors’ homes burn completely.” An urban setting with small setbacks bolstered these concerns, and toxicity concerns also were a factor for Gleba.

The vapor-permeable, airtight design started with Tyvek as the weather-resistive barrier wrapping the sheathing, then two layers of Roxul Cavity Rock—an inner 4" layer of lower density and an outer 2" layer of higher density. Wood furring strips held the insulation in place, with metal siding topping it off. More options would have been possible on the roof, including fiberglass, but the client chose to stick with mineral wool there as well, says Yanowitz, and the home got three layers of batts. The project wasn’t die-hard about avoiding foam, though: a fieldstone foundation required closed-cell spray foam.

The project was pricey, acknowledges Yanowitz, but was supported by a utility program that is trying to spur more deep energy retrofits. He was pleased by the buildability: “I found a willing carpentry crew that was willing to do it,” he says, and while they were skeptical at the start, by the end several members of the crew wanted to retrofit their own homes with the technique.

The Replacements

Larry Nordin, AIA, also from SCB Architecture, spoke for a number of the designers BuildingGreen interviewed in saying, “We’re searching for thin, efficient materials that don’t have some of the concerns that the foams do.” But the same thing holds true for insulation as for rock ’n’ roll tribute bands: the most intriguing imitations are those that develop their own personality.

For example, while he hasn’t yet used it, Stopka is excited about the Dow Corning Building Insulation Blanket, an aerogel-impregnated silicon felt material that is being marketed as a thermal break in difficult-to-insulate locations. The 10 mm (0.4") thick material offers R-8.1 per inch in the silicon version and R-9.6 per inch in a version that uses a plastic. (Dow Corning would not divulge the nature of the plastic to BuildingGreen but stated that it was not PVC and did not contain flame retardants.) The silicon version is rated as noncombustible, while the polymer version is rated as Class A per ASTM E84—relatively fire-resistant. At about $10/ft2, according to Dow Corning, it is suited for targeted use in slab edges, king studs, and parapets, where insulation is commonly omitted. Even if a thin layer of the blanket only insulated such a detail to R-3.5, the heat loss reduction would be significant. It can wrap around corners.

Designers BuildingGreen spoke with have taken note of wood-fiber insulation and sheathing that is more common in Europe but has started to become more accessible in North America in the past few years with the import of Agepan, BuildingGreen has reported. Wood-fiber sheathing like Agepan doesn’t insulate as well as rigid foam (typically offering R-3 per inch), but it is vapor-permeable, and some designers are using it to design walls that dry in both directions.

Every product has its downside: Straube calls Foamglas “the cat’s meow,” noting that it doesn’t burn, is impervious to moisture, and has decent R-value (R-3 per inch), but says, “Unless they can cut the price at least in half, it’s not going to make an impact.” According to Baum, however, the obstacle she’s seeing to Foamglas isn’t cost but rather how it’s specified. “In Europe, Foamglas is a material that roofing companies can work into their systems and warrant the whole roofing system,” she says, and “this means that different roofing companies compete based on their whole system.” In the U.S., Foamglas would be specified as an individual product, not part of the roofing system, and its status as a single source product can be challenging. Even though it’s made in the U.S.A., that makes it less competitive.

See the table “The Replacements” for a more thorough listing of specific insulation materials and pros and cons in relation to foam.

Constantly Looking at Tradeoffs

Between the conventional options that remain available, old materials like cork and mineral wool that are back in vogue, and new developments like aerogel products, today’s designer or builder has more insulation options than ever before. That doesn’t mean that we have what we want. Intriguing products remain continually over the horizon: Evocative Design in New York has been Myco Foam mycelium-based insulation for years. The company is developing products—including a replacement for polystyrene packaging that is already on the market—that are grown by fungi on waste agricultural materials.

“Maybe there will be one day, but there’s no perfect insulation right now,” says Stopka. “Sometimes the spray-foams or boards have so many advantages. We constantly have to look at the tradeoffs, and we continue to push for using alternatives on all projects whenever possible.”

One thing is clear from project teams that have tried to kick the foam habit: you have to really work at it. But with more project teams aiming for higher overall levels of insulation and paying close attention to critical details while being aware of what ingredients they’re putting in their buildings, we’re arguably in one of the most creative and environmentally innovative stages of development the industry has yet seen.

Also worth reading

If you enjoyed this article and want to learn more detail about all the different types of insulation and performance attributes and cost considerations for alternatives, read The BuildingGreen Guide to Insulation.

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.