As the Trump administration takes the reins of power this month, the environmental community faces a new reality.

As the Trump administration takes the reins of power this month, the environmental community faces a new reality.

Assuming confirmation, we are looking at:

- an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator who denies climate change and has been fighting environmental regulations for decades;

- a Secretary of Energy who in an earlier presidential primary campaign famously couldn’t remember that it was the Department of Energy that he wanted to shut down; and

- a Secretary of State who has served his entire career with one company—the largest oil and gas company in the world and the fourth largest corporate emitter of carbon dioxide at 555 million metric tons per year (2013), according to an August 25, 2016 article in the journal Science.

The rules of the game will be different, for sure. There will be huge new challenges, certainly. But along with those challenges we may find a few opportunities. This is a good time to take a hard look at where we are and what we, in the environmental community, need to do in the immediate future.

When Nadav and I launched Environmental Building News (now The BuildingGreen Report) 25 years ago—in 1992—we had a clear purpose. We weren’t merely going to report on the fledgling green building movement; we set out to make a difference in the mainstream building industry.

Our mission sets us apart from most publishers and most companies, but it has served us well over the last quarter-century. It is why our staff of 14 is so dedicated and works so hard. Having a strong corporate mission also calls for us to remind ourselves, every once in a while, just what it is that we’re working toward.

With this essay, I’m articulating some big-picture thoughts on where we need to be going as an industry and as a country—and what our priorities should be as we look to the future. While this essay has been reviewed by our editorial team at BuildingGreen, it does not necessarily speak for all of us. It is my own personal perspective on our priorities, on where we in the green building movement should be directing our efforts. Others on our team will have somewhat different perspectives on these priorities—and that’s a good thing.

This essay is divided into two parts:

- First is a list of macro-scale priorities related to the environment and social justice. These are priorities that apply either nationally or worldwide. Most are broad in scope; a few are more specific. Some will be controversial.

- Second is a list of more specific actions that relate more directly to the built environment. Most of these are policy-level actions. All will be exceedingly difficult to achieve.

General Priorities Nationwide and Globally

1. Find common ground amid the partisanship that divides us

As became crystal clear in the recent presidential election, we live in a divided land. While there have always been ideological divides—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing—those divides have become chasms. There are even different sets of “facts” upon which we base our decision-making, and most Americans now get their news not from widely respected sources like Walter Cronkite’s CBS of the 1960s and ‘70s, but rather from partisan networks and even fake news streamed over the Internet. It’s hard to tell what is real anymore.

We need to find common ground, and build back a level of trust and productive discourse from that. With a topic like climate change, we need to listen to the other side and respond respectfully.

When I was speaking at a conference in Ohio last year, it was very clear that the audience was deeply divided about the reality of climate change. I described my own experience since the early 1970s as an avid student of climate change. I referred to Congressional Reports I have on my shelf from the 1970s that describe the then-prevailing belief by many scientists that we were likely to enter a period of cooling or even a new ice age. Having followed that scientific debate 45 years ago, I can understand how many people would be skeptical of a seeming flip-flop in the scientific circles.

I went on to explain in that Ohio conference, that as a trained scientist I listen to the evidence and draw conclusions accordingly—and the vast preponderance of scientific evidence in the past four decades points to global warming, not cooling—but I can understand how a lot of people could have doubts. Telling that story helped to lower some of the walls that an earlier speaker—a climate scientist—had created.

I am optimistic that there will be some common ground between the incoming Trump administration and the environmental community. Not that there won’t be big setbacks for environmental priorities, but there are some issues that we can all agree on—like a need for clean air, or a desire to have pristine woodlands that we will be able to enjoy with our grandchildren, whether for hiking or for hunting.

We need to find those places of common ground and work from there in respectful dialogue.

2. Achieve near-universal acceptance of the reality of anthropogenic climate change and the need to do something about it

This will be harder to achieve, but I believe it’s possible.

It will start with those of us who accept the science of climate change sitting down with those who question the science. We can’t simply dismiss climate change deniers as idiots; we have to talk with them in a reasoned way that respects where they are coming from. This is hard. I believe the challenge will be eased with each new temperature record or news story about routine tides flooding streets in South Florida.

It will start with those of us who accept the science of climate change sitting down with those who question the science. We can’t simply dismiss climate change deniers as idiots; we have to talk with them in a reasoned way that respects where they are coming from. This is hard. I believe the challenge will be eased with each new temperature record or news story about routine tides flooding streets in South Florida.

Evidence will be on our side (unfortunately), and I believe that more and more of those who are most entrenched in denial will give in to the realities of what we are facing as the effects become harder and harder to ignore. I actually believe that there is a chance (not a chance I’d like to bet money on, but a modest chance) that President Trump could bring about rapid change in public perceptions of climate change if he were to accept the science and be convinced of the need to take action. If this happens, I predict that it will be the military that convinces him of the science and the urgency of action—because climate change is a national security issue.

What gives me the greatest sense of hope is that if the Trump administration could be convinced of the reality of anthropogenic climate change and the need to tackle it, that administration would be better able to convince a Republican Congress to take action than was the Obama administration. Even Rex Tillerson, of Exxon-Mobil, has publicly stated that he believes in the science. Just as the firmly anti-Communist President Nixon was able to open up relations with China, the Trump administration, populated by fossil fuel interests, could have the ability to bring about real policy changes. (This is a big “if,” of course, since Trump has previously denied climate change.)

I have long believed that once we as a nation finally get behind the reality of climate change and the need to very quickly eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, we will jump into action—as occurred in World War II with the rapid re-tooling of American industry. Having delayed this time of reckoning as long as we have, achieving the needed changes will be all the more difficult, but we really haven’t any choice.

3. Build awareness of the need to address resilience in addition to sustainability

Even before we are able to achieve near-universal agreement that humans have brought about global warming, we should be able to convince a large majority of Americans—and others worldwide—to begin preparing for those changes. Implementing strategies for adaptation to climate change can be a fairly easy sell because the same solutions make sense whether we are adapting to a changing climate or protecting ourselves from other vulnerabilities, be they terrorism, intense storms, earthquakes, or coastal flooding. Fortunately, some of the leading resilience strategies are also sustainability strategies—but with a motivation of human safety rather than environmental protection.

We can be convinced to buy property insurance as individuals. The same should apply to resilience and adaptation to climate change. Yes, it may take a few more Katrina’s and Sandy’s, but I think the motivation will be there fairly soon. We need to continue building the knowledge base of how to achieve resilience, something that a lot of us are beginning to focus attention on. (Disclosure: in addition to my limited role at BuildingGreen, I am also president of the Resilient Design Institute, which is working to do just that.)

The challenge—and what we need to guard against—is that there will be a temptation to invest in resilience in place of investing in sustainability. We need to invest in both simultaneously. To do that, we’ll need to make a strong case that sustainability—conserving natural resources, preserving biodiversity, protecting natural areas, and such—offers wide-ranging benefits to all of us. Ecosystem services will need to become part of our economic lexicon.

The challenge—and what we need to guard against—is that there will be a temptation to invest in resilience in place of investing in sustainability. We need to invest in both simultaneously. To do that, we’ll need to make a strong case that sustainability—conserving natural resources, preserving biodiversity, protecting natural areas, and such—offers wide-ranging benefits to all of us. Ecosystem services will need to become part of our economic lexicon.

4. Come to grips with a growing world population

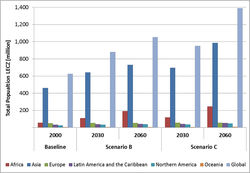

It’s the issue that no one wants to talk about, but it’s the looming 800-pound gorilla in the room. With a rapidly growing world population, and with large segments of that population becoming more prosperous and (rightfully) expecting a higher standard of living, the world’s resources are being dramatically overtaxed. Climate change will exacerbate this problem because such a large percentage of the world population lives in coastal regions. In 2000, 625 million people lived in low-elevation coastal zones (less than 10 meters above sea level), according to a 2015 paper in the journal PLOS ONE, and that number is projected to increase to between 1.05 and 1.39 billion by 2060. We need to bring population into the discussion and work quickly to slow, and then reverse, population growth. Stabilizing the world population at 11 billion people, as is currently projected by the UN—while raising the standard of living globally—probably isn’t feasible from a resource standpoint; we need to aim for a lower population.

One of the most effective environmental organizations today—which few people have even heard of—is the Global Footprint Network. This nonprofit has been measuring the resource consumption of nations and translating that information into easy-to-understand metrics that may help us address these huge challenges. “You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” the old adage goes, and the Global Footprint Network is providing us with a way to track our consumption.

Fortunately, there are some bright signs on the horizon. Population levels in some European countries and Japan have already peaked and begun declining, and the growth curve is slowing in many developing countries. In Brazil, for example, the family size has plummeted in recent decades—from 6.15 children per woman in 1960 to less than 1.8 in 2016, according to a 2011 Washington Post article and World Population Review—despite limited access to contraceptives and other family planning resources. As women become more educated and as their standard of living improves, their desire to bear large families drops (see Priority #9 below).

5. Begin talking about the transition from a growth economy to a steady-state economy

Today in the United States, as elsewhere, economic success is largely measured by growth—growth in wages, growth in a company’s quarterly profits, growth in the gross domestic product, growth in our stock indices. For a politician to stand up today on the campaign trail and suggest that growth won’t continue forever would be political suicide. Whether Democrat or Republican, belief in sustained growth is absolute dogma.

Yet, we know that growth can’t be maintained forever when it relates to populations or resource consumption. The late Kenneth Boulding famously said at a Congressional hearing in 1973 that “anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

Yet, we know that growth can’t be maintained forever when it relates to populations or resource consumption. The late Kenneth Boulding famously said at a Congressional hearing in 1973 that “anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

Inevitably, there will need to be a transition from the growth economy that the world has enjoyed since the Industrial Revolution to a steady-state economy that reflects sustainability rather than growth. That transition will be bumpy, as Paul Gilding points out in his 2011 book, The Great Disruption (you can get the gist of his argument in this 2012 TED Talk), but if we are aware of that transition, we can begin planning for it and lessen the impact.

The problem is that, like a massive Ponzi scheme, our economic engine depends on growth, and at some point—in ten years or 50 years or 100 years—that spigot of growth will slow to a trickle. Some areas of the economy can—and should—continue to grow for a long time, such as renewable energy, but ultimately segments of the economy that grow will need to be offset by segments that shrink. We need to begin talking about this reality.

6. Adopt a pricing mechanism for carbon

The sooner we monetize carbon (and other greenhouse gas) emissions, the sooner the free market can get to work saving money and helping the environment by reducing those emissions. It is now well established that there are huge societal costs associated with our fossil fuel use: health costs from air pollution, cleanup costs from environmental spills, defense costs for ensuring our continued access to oil in volatile regions of the world.

An analysis by Drew Shindell, Ph.D., of Duke University, in the May 2015 issue of the journal Climate Change, concluded that the health and environmental costs associated with conventional energy consumption are enormous (see table). These are huge costs, often exceeding the commodity cost of the energy source. The cost is borne by society, though, and it makes good economic sense to reflect that in our pricing.

There is support, even among some Republicans and Libertarians, for taxing carbon and then getting out of the way and letting the free market sort out which solutions to implement. N. Gregory Mankiw, the Harvard economist who was chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors, explained in this 2015 Op-Ed article in the New York Times why a revenue-neutral tax on carbon is so attractive to even conservative economists. This approach has worked very well with other challenges, such as tobacco, and even Rex Tillerson has offered modest support for the idea of a carbon tax. Cap-and-trade is another option for monetizing carbon (as was done with sulfur and nitrogen pollutants from power plants), but it would be more complicated to implement broadly.

7. Remove both direct and indirect fossil fuel subsidies

We subsidize the fossil fuel industry in many ways, including oil depletion allowances, rapid deduction of oil and gas drilling costs, the exemption from paying royalties on offshore oil rigs, tax credits for oil and gas exploration, and deductions for oil spill cleanup. Collectively, these direct subsidies total about $4.3 billion per year in the U.S., not including low-income fuel assistance, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Indirect subsidies include military costs for protecting our access to oil (such as in the Middle East), healthcare costs that result from oil and gas production and use, and the tremendous costs associated with climate change. The International Monetary Fund estimates that total subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, worldwide, including these indirect subsidies, cost about $5.3 trillion per year.

Indirect subsidies include military costs for protecting our access to oil (such as in the Middle East), healthcare costs that result from oil and gas production and use, and the tremendous costs associated with climate change. The International Monetary Fund estimates that total subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, worldwide, including these indirect subsidies, cost about $5.3 trillion per year.

Most environmentalists, myself included, would be fine if subsidies on renewable energy sources were eliminated, as long as the same were done with fossil fuels. It’s worth noting that of our current subsidies for renewable energy, about half are for corn ethanol—which is environmentally damaging and may not even return as much renewable ethanol as is consumed in fossil fuel by producing it.

8. Protect biodiversity

Many of our assaults on the environment are temporary. Air and water pollution will dissipate in a few years if the sources are controlled. Releases of toxins can become part of the earth’s geologic heritage—thin bands that would be isolated, millennia from now, by cleaner sediments above. Even global warming could become a somewhat temporary phenomenon if we are able to curtail greenhouse gas emissions before catastrophic, planetary changes occur through feedback loops. But the loss of species in the natural environment is far more permanent.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (2014), provides a sobering look at this issue and the need to address it. Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, who coined the term “biodiversity” in 1988, argues in his most recent book, Half Earth, that slowing the dramatic increase in species extinctions requires that we set aside fully half of the land area on earth as protected wild area.

While protecting biodiversity is important for nature, it’s worth pointing out that there are a lot of tangible benefits to protecting natural areas. Many of our most important medicines have been derived from plants, and new cures are being discovered every year in tropical ecosystems that are threatened with destruction. Here in the U.S., ecosystem services that protect and purify water, pollinate our agricultural crops, provide erosion control, protect our coastlines from storm surge, and sequester carbon, are providing billions of dollars in value per year to our economy.

In a time when environmental protection will be under fire with the incoming Trump administration, the need to protect biodiversity worldwide should be near the top of our environmental priorities.

9. Elevate the stature and education of women globally

When abject poverty, high infant mortality, and the immediate needs of procuring food and water dominate daily life, environmental protection can rank pretty far down the list of priorities. And if few of one’s children are likely to survive to adulthood, there is strong motivation to bear more children—growing the population and exacerbating resource shortages and environmental burdens.

Solving these related problems depends on educating more women in the developing nations of the world. Numerous studies have shown that when women achieve an education and greater empowerment, the desired family size drops and the quality of living increases. This is a win for those women, for their families, and for the earth.

Solving these related problems depends on educating more women in the developing nations of the world. Numerous studies have shown that when women achieve an education and greater empowerment, the desired family size drops and the quality of living increases. This is a win for those women, for their families, and for the earth.

Not only should we work to support education campaigns, women’s resource centers, and related programs worldwide, but we should work to reverse the backsliding that has been occurring for women with the increase in radical Islamic cultures in parts of the Middle East and Northern Africa. It is unclear how best to do this, but some nonprofit organizations, such as the Population Media Center and PCI Media Impact, I believe, are on the right track in working with in-country partners to produce radio serial-dramas that achieve large listener audiences and portray strong, educated role models in their female characters.

10. Overturn Citizens United

In 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case known as Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission that the First Amendment rights of free speech extended to corporations, including partisan nonprofit organizations, such as Citizens United (which wanted to air a movie critical of Hillary Clinton during the 2010 primaries). In this 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court overturned key provisions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, commonly known as the McCain-Feingold Act. The ruling opened a floodgate of corporate influence in political campaigns. Overturning that action through a constitutional amendment that imposes strong limitations on corporate influence on elections is seen by many as a top priority.

The chance of adopting such a constitutional amendment is exceedingly unlikely in a Congress controlled by Republicans, but I hold out a sliver of hope of success. If President-elect Trump truly considers himself a “populist” politician and truly represents the anti-establishment interests among the working-class Americans who elected him—people supporting his call for "draining the swamp"—then perhaps he could be convinced to push through such a constitutional amendment, dragging a Republican Congress and Republican-controlled state legislatures along with him.

Along with Citizens United, we should keep an eye out for other hidden opportunities in which the populist and business interests of Trump might be parlayed into positive change. In the campaign, Donald Trump reached out to progressives who supported Bernie Sanders, and some of those progressives supported him. Perhaps that segment of the populist electorate can convince Trump to surprise us!

Along with Citizens United, we should keep an eye out for other hidden opportunities in which the populist and business interests of Trump might be parlayed into positive change. In the campaign, Donald Trump reached out to progressives who supported Bernie Sanders, and some of those progressives supported him. Perhaps that segment of the populist electorate can convince Trump to surprise us!

What All This Means Relative to Building Design and Green Building

The above priorities provide some general direction and guidance for addressing the huge environmental challenges we face. But most of them are not specific to our wheelhouse: building design. What are our priorities as a profession—as part of the building design community that is committed to environmental sustainability?

1. Really commit to the 2030 Challenge

The Architecture 2030 organization and its founder, Ed Mazria, FAIA, have played an important role in providing a specific target for the building design community in slowing climate change. That is important—really important—and we need to get more architecture working to meet the 2030 Challenge. Signing on to the AIA 2030 Commitment isn’t enough. While the 2030 Commitment provides a much-needed process for tracking progress toward the 2030 Challenge, our profession needs to push harder for achieving the goals laid out in the Challenge. Many firms that signed on to the Challenge haven’t been able to deliver on the commitment for various reasons, including tight construction budgets and an inability to achieve buy-in from clients.

To succeed with the 2030 Challenge, we need to look for incentives that can help to boost participation and maximize the success rate with compliance. Firms should consider some sort of in-house recognition that rewards carbon-neutral or net-zero-energy (NZE) design. We should also work more actively on education and publicity to build an expectation for NZE buildings at universities, municipalities, and corporations. We can’t expect to design NZE buildings if our clients aren’t asking for them—or, better, demanding them.

In our roles on planning commissions and zoning boards, we should look for ways to incentivize NZE or carbon-neutral buildings: speeding approvals, increasing floor-area ratios, allowing greater density, reducing permit fees, etc. In my little town of Dummerston, Vermont, our Energy Committee (which I chair) has proposed waiving or discounting building permit fees for buildings designed to achieve NZE performance. That wouldn’t be a huge incentive, but it might at least raise awareness of the issue and the benefits that would accrue to such buildings.

At the same time, we should push for stronger building codes to mandate NZE, as California is doing with some building categories and the City of Vancouver is doing with all new construction. For larger buildings that can’t reasonably achieve NZE with renewable energy sources on the building, we should expand the scale to building clusters or neighborhoods, as BuildingGreen proposed in a 2010 feature article.

Finally, NZE should be firmly integrated into our architecture school curricula and Architectural Registry Board requirements. It shouldn’t be possible to graduate from architecture school or become a licensed architect without a strong working knowledge of NZE and carbon-neutral design. These terms—and other terms like them—need to be firmly planted in the architectural lexicon.

Finally, NZE should be firmly integrated into our architecture school curricula and Architectural Registry Board requirements. It shouldn’t be possible to graduate from architecture school or become a licensed architect without a strong working knowledge of NZE and carbon-neutral design. These terms—and other terms like them—need to be firmly planted in the architectural lexicon.

2. Eliminate fossil fuels in all new buildings

An important step on the path to net-zero-energy, carbon-neutral buildings would be to eliminate fossil fuels from all new buildings. Even for buildings that aren’t being designed for renewables and NZE, designing them to operate solely on electricity makes future conversion to NZE much easier, because electricity is increasingly the currency of renewable energy.

Having electricity as the sole energy source of a building facilitates easy tracking of the building’s energy balance. Electricity consumption and renewable electricity production are really easy to measure and display, and doing so will help us better manage our buildings.

Also, eliminating fossil fuels from buildings would increase safety (no natural gas explosions), health (no release of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other byproducts of combustion), and environmental protection (spillage or leakage of electricity doesn’t result in environmental contamination).

It’s time to stop dancing around this issue and simply exclude fossil fuels from our buildings.

3. Upgrade the energy performance of existing buildings

While it’s relatively easy to achieve superb energy performance—even net-zero-energy—with new construction, that goal is far more difficult to achieve with existing buildings. But it is with our existing housing stock and commercial buildings that the heavy lifting will have to occur if we are to dramatically reduce the carbon emissions from the building sector. This needs to become a driving focus of our profession.

Exactly what it will take to accomplish this is the challenge. For starters, we should continue the trend toward mandatory annual reporting of energy consumption of large commercial buildings—currently required by law more than 20 cities in the U.S. and two states. We should expand that requirement nationwide and broaden the applicability to all buildings—though for homes and smaller commercial buildings, reporting at the time of sale would probably suffice.

We should push for tax credits and other incentives to improve the economics of deep-energy retrofits that reduce energy consumption by at least 75%. The modest tax credits that supported various residential energy-efficiency improvements (capped at $500) expired at the end of 2016, though the unlimited solar energy tax credit continues at 30% through the end of 2019, and then drops to 26% for tax year 2020 and 22% for tax year 2021, after which it expires.

To incentivize deep-energy retrofits, though, we will have to get creative. Perhaps the historic preservation tax credits can provide a model, or property tax reductions, or accelerating the permitting process—all of which have been implemented in various states, cities, and towns. (Refer to the Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency, DSIRE, for more on state and federal incentives.)

4. Codify passive survivability in buildings

Passive survivability is the idea, first advanced in the pages of this publication in 2005, that buildings should maintain habitable conditions if they lose power for an extended period of time, and this has been a significant focus of the Resilient Design Institute since that organization’s founding in 2012. My sense of the importance of this design criterion has only increased after reading Ted Koppel’s provocative 2015 book, Lights Out: A Cyberattack, A Nation Unprepared, Surviving the Aftermath.

What is clear to me is that passive survivability is a life-safety issue for buildings in an era of increasing vulnerabilities—whether from earthquakes, terrorist actions, or more intense storms with climate change. As such, providing for passive survivability should be written into building codes, which exist largely to protect building occupants.

What is clear to me is that passive survivability is a life-safety issue for buildings in an era of increasing vulnerabilities—whether from earthquakes, terrorist actions, or more intense storms with climate change. As such, providing for passive survivability should be written into building codes, which exist largely to protect building occupants.

The good news is that such a requirement in building codes would align well with the call for net-zero-energy buildings. Buildings designed to achieve passive survivability will have highly insulated building envelopes, cooling-load-avoidance features, natural ventilation, and passive solar heating—in short, they will be green buildings that could easily achieve NZE performance, if they don’t already.

5. Incorporate energy storage into buildings

As more buildings are constructed that operate on a net-zero-energy basis with grid-connected roof-integrated or ground-mounted solar arrays, we will have to face the reality that electricity demand does not always match renewable electricity production. Utility companies and public service boards will reduce incentives for net-metered solar systems, as we are already seeing across the country. To make distributed solar generation more attractive to utility companies, electricity storage will need to become part of the equation.

Storage will be the new frontier in the renewable energy industry. And the design and construction industry will have to figure out how to integrate energy storage into buildings. The opportunities are huge, including the potential to integrate electric vehicles into the mix, an idea that has been advanced by the Rocky Mountain Institute and Tesla.

In commercial buildings, thermal energy storage provides another—quite different—way to smooth electrical loads and manage peak demand. A number of companies, including CALMAC, Baltimore Aircoil, and Thule Energy Storage (formerly IceEnergy), manufacture such systems for both large and small buildings. While there are more than 40,000 thermal energy storage systems in place worldwide, there is far greater potential for this technology, which is typically more cost-effective than battery storage, though more limited in what it offers.

6. Advance and support the integrative process in building design

The era of an architect designing a building and throwing the design over the wall to the mechanical engineer to heat and cool it needs to be put to rest.

Many of the design and technology solutions that are so important for the building industry as we strive for greater sustainability and resilience are built on the platform of an integrative process. Our building systems interact: lighting designs affect thermal loads, building orientation and fenestration have a huge impact on cooling.

Many of the design and technology solutions that are so important for the building industry as we strive for greater sustainability and resilience are built on the platform of an integrative process. Our building systems interact: lighting designs affect thermal loads, building orientation and fenestration have a huge impact on cooling.

The many players needed to create a well functioning, environmentally responsible building must work together from the beginning to identify and implement solutions. This integration of the design process needs to be instilled in our architecture and engineering schools as a foundation of learning.

7. Get toxic and carbon-intensive materials out of buildings

As we learn more about the hazardous constituents of building materials and their impact on human health and the environment, the excuses for continuing to use them in our buildings are becoming ever flimsier. We are increasingly able to identify those chemicals or constituents through various red lists that identify materials to avoid. Such lists include halogenated flame retardants, carcinogens, mutagens, endocrine disruptors, and other toxic substances.

The red lists that identify hazardous compounds are typically only considered when using a robust rating system like the Living Building Challenge, or when working for progressive companies such as Google or Kaiser Permanente that specifically seek to exclude such materials. Avoiding these hazards needs to become more mainstream. To aid the design community with this effort, building product manufacturers need to be more transparent about the constituents of their products. We need to insist on that. And architecture schools need to begin adding courses on toxicology and material science to their required curricula.

Beyond the usual definitions of toxicity, we need to begin paying attention to the global warming potential and carbon intensity of our materials. As the energy consumption of our buildings drops, the embodied carbon of the building itself (the carbon emitted into the atmosphere in the production and shipping of the materials and products that went into building the structure) becomes more important. Such information is typically found in Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs).

Continuing to make progress in reducing the carbon intensity of our buildings will increasingly depend on the selection of low-carbon materials.

8. Compromise on wood product certification

It’s no secret that antagonism between the timber industry and the environmental community runs high. Environmentalists push hard for wood products that carry the most stringent environmental certification (typically Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification), while the timber industry pushes for a less robust certification, such as wood from Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) forests. While I have long been a proponent of FSC certification, I also feel that SFI-certified wood is a lot better, from an environmental standpoint, than non-wood products, such as steel, concrete, and vinyl.

I would like to see the green building community build a bridge to the North American timber industry. There are many shared values that have been lost in the contentious debates over the past two decades, and I believe there is an opportunity to create a positive working relationship. With the approval of a pilot credit on legal wood in LEED, some of this is already happening, because SFI-certified wood is now recognized. But I think we can go further by more actively promoting wood as a way to reduce the carbon intensity of our buildings.

In exchange for recognizing less robust certifications like SFI and American Tree Farm System, I would like to see a commitment from the timber industry to more aggressively police illegal logging and to require timber imported from developing nations to carry FSC certification (in part because of FSC’s focus on protecting indigenous cultures). The green building community could also broker changes to FSC to make it less onerous and expensive to landowners, cabinet shops, and other users of wood products.

To continue the divisiveness that exists between the timber and environmental communities will continue to slow the more widespread implementation of green building practices, and could result in more outright prohibitions on green certification (including LEED) that have been instituted in various states. By building a bridge to the timber industry, the environmental community could have a voice in further strengthening SFI standards. And, by working together, we can significantly increase the use of carbon-sequestering wood, such as cross-laminated timber, in our buildings to reduce their carbon footprint.

To continue the divisiveness that exists between the timber and environmental communities will continue to slow the more widespread implementation of green building practices, and could result in more outright prohibitions on green certification (including LEED) that have been instituted in various states. By building a bridge to the timber industry, the environmental community could have a voice in further strengthening SFI standards. And, by working together, we can significantly increase the use of carbon-sequestering wood, such as cross-laminated timber, in our buildings to reduce their carbon footprint.

9. Increase research funding in the building industry

Compared with other sectors of our economy, the building industry devotes an embarrassingly small percentage of revenues to research and development. According to the (somewhat dated) book Building for Tomorrow, the U.S. construction industry invests about 0.4% of sales in research and development, while architecture and construction firms invest just 0.05% of sales in R&D. We are facing huge challenges, and solving those challenges will require continued innovation. Integrating renewables seamlessly into buildings, incorporating energy storage into buildings, developing affordable deep-energy-retrofit systems for homes, and inventing safer and healthier building materials all could benefit from increased research.

We need breakthrough technologies and products, and we will get a lot more of them if we invest reasonable money in R&D. With a new administration in Washington this month, we will be less able to depend on government funding of this R&D; it will be up to industry to fill the void. Manufacturers of building products, appliances, HVAC equipment, lighting, renewable energy systems, and batteries all need to step up to the plate. Significant tax credits exist for companies, including architecture firms, that invest in R&D.

10. Make social equity a more explicit part of green building

Many of us in the green building community have been myopic in our perspective—considering only environmental impact or indoor air quality. We need to expand our focus to encompass social equity. All too often, today, green building is seen as a luxury for those who can afford it.

We need a bigger tent. We need to consider the social wellbeing of people in the communities we create in our project development. We need to incorporate our leading-edge green building practices not only into Class-A office space and institutional buildings, but also into affordable housing. We need to consider the impacts of resource extraction and building product manufacturing on the communities where those activities take place—often low-income communities where residents are locked into a vicious cycle of dependency on the industries that are poisoning them.

To accomplish this, we need to bring more diversity into the green building community. We should be actively reaching out to people of color for our conferences, for our committees, and for the discussions that happen with every building project.

Final Thoughts

The purpose of this essay has been to spur big-picture thinking, so that we can enter this period of change having already thought about our priorities and how we might want to strategize in moving forward.

To continue making progress in reducing the environmental footprint of buildings during the Trump administration, we will need to think creatively. We will need to search for win-win solutions. We will have to focus on the economic arguments for the green building strategies we are pursuing. And, as noted in my first recommendation, we will need to build bridges—not walls.

It gives me some hope that even Glenn Beck, long a paragon of the political Right, can recognize the damage that he did through his highly charged and divisive commentaries, and has significantly softened his approach.

We look forward to your thoughts on all this. Use the Comments field below to join in the conversation. What do you think the top priorities are for the green building movement? How can we work with the Trump administration?