A design team can enable real progress by setting aside a day or longer for a focused workshop. Or it could just waste a lot of high-priced time.

A design team can enable real progress by setting aside a day or longer for a focused workshop. Or it could just waste a lot of high-priced time.

You can break down barriers and build a functioning team if you bring together people in different roles who don’t usually get to talk with one another. Or you might just reinforce existing stereotypes.

Get the right kind of discussion going, and you can move as a team toward innovative solutions. Or you can squeeze the life out of a room with an agenda that feels like a forced march.

This article is about design workshops: who, what, where, when, and why. My hope is that in reading it, you’ll pick up at least three ideas that you can’t wait to apply in your next workshop—whether it’s a short internal meeting, a half-day design exercise, or a long charrette with dozens of people.

If this article had an agenda, it would be a pretty loose one.

We’ll start off talking about what kind of mindset to bring into a workshop, then move to:

- how to plan one

- what kinds of exercises to do

- some ideas for follow-up

You can read it from start to finish, or skip around and pick out what’s useful.

Whatever ideas or thoughts it sparks, or whatever feedback you have, please consider sharing. There’s a flipchart and marker (actually just a comment form) down at the bottom of the page.

How to Get into the Right Mindset

Choreographing the project process includes designing key components, clarifying the role of workshops in a healthy process, and identifying what you call them and who should attend, among other things.

1. Think big, together

An early design workshop and a collaborative design process go hand in hand. While this article doesn’t go into the value of integrative design (see How to Make Integrated Project Delivery Work for Your Project and Integrated Design Meets the Real World), let’s take a minute to talk about the value of a day-long (or longer) workshop with a large group of stakeholders.

The Oregon Sustainability Center didn’t get built, but its five-day design charrette led to numerous design breakthroughs, including at least one that has been used on other projects, according to Lisa Petterson, AIA, senior associate at SRG Partnership. Part of the workshop was focused on structure, and Petterson says that the structural engineer wanted to use a box beam. “It wasn’t so terribly revolutionary,” she says, but it would be applied on a relatively large scale, opening up new possibilities. “Everyone got excited,” says Petterson. The mechanical engineer and the plumbing engineer had a place for ducts and pipes inside the beam. The lighting designer was happy at the prospect of a clean ceiling. “Everyone had a place in this structural system for their discipline.”

That idea didn’t last, however. The site was constrained by transit on three sides, and there wouldn’t have been room for cranes to safely erect the structure. The design moved to a more conventional solution for Portland: a post-tensioned slab. But the idea of integrated HVAC and structure stuck around. According to Petterson, the team asked, “Why shouldn’t we put radiant heating and cooling in the post-tension structure?” It hadn’t been done, but the group, already functioning well as a team, took the time to coordinate on the design and embed hangers in the slab.

In the end, the whole project was shelved, but the viability of the solution has been proven out on other projects that have used it, according to Petterson.

2. Hold a workshop, not a charrette

The term “charrette” isn’t going away anytime soon. However, a number of people we spoke to for this article prefer to call an extended design meeting simply that—a meeting, or, more often, a workshop.

“Charrette” refers to the cart that would come around to the design studio in 19th-century France, picking up student work for review. “As the cart made its way by, you would likely be rushing to get every last line on the drawing or piece of wood in the model,” says Jennifer Preston, sustainable design director at BKSK Architects. The frenzy and anxiety of that scene, as well as the focus on the realm of the designer, is not what we need when we bring together project teams, she argues. “What our process needs is less speed for speed’s sake and more thoughtful decision-making.”

Clark Brockman, AIA, principal at SERA Architects, agrees, adding, “Clients are more comfortable investing in a workshop” than a charrette.

Even if you prefer the word “charrette,” don’t call it an “eco-charrette.” That term feels dated—for a couple reasons. One is that the “eco-charrette” has become associated with a dry exercise of dragging team members down a checklist. Also, treating sustainability as a separate topic in its own silo simply doesn’t support an integrative process; it allows those concerns to be marginalized and green features to be value-engineered out.

None of this is to suggest that having a multi-day workshop isn’t worth it. If anything, the evidence is that having a workshop moves a project along quickly and to a high level of performance. And there is a trend of projects that do multi-day events to dedicate day-long workshops to sustainability-related topics like daylighting and biophilia. As discussed throughout this article, the time invested in building a team and exploring key issues pays off over and over again.

3. Call in a facilitator from outside the team

The professionals we spoke to for this article agreed universally on the importance of dedicated facilitation in a design workshop or charrette. An architect at a firm can be a skilled facilitator, but there are advantages to bringing in a third party, says Josie Plaut, associate director at the Institute for the Built Environment, which provides facilitation services.

Without a facilitator, the emotional intelligence and inclusiveness in the room drop, says Plaut, or the conversation gets centered around the person who is most powerful but who might not contribute the most. “Without a facilitator, you can still have all the same people in the room but be playing a different game.”

A 2015 white paper, The Social Network of Integrative Design, from the Institute for the Built Environment, argues that a third-party facilitator is in the best position to create an effective team environment because that is their sole agenda.

The paper defines a third-party facilitator as either someone from outside the design firm, who may be a consultant on high-performance buildings, or a member of the design firm but without design responsibilities. They may have specialized training or tools.

According to the paper, dedicated facilitators offer three key benefits to design teams:

- They foster a safe environment where everyone can freely express opinions.

- They help increase the interaction among architects and other team members.

- When architects are participating rather than facilitating, they learn more and build stronger relationships with the participants.

Other experts note that it’s valuable for the facilitator to have a designated point person in the group, such as a lead architect, to check in with. The facilitator can only read the room so much while also running a meeting. They benefit from having a second perspective, and someone to huddle and strategize with as the day moves along. The same person, possibly as part of a core group of participants, can help the facilitator plan the event.

Other experts note that it’s valuable for the facilitator to have a designated point person in the group, such as a lead architect, to check in with. The facilitator can only read the room so much while also running a meeting. They benefit from having a second perspective, and someone to huddle and strategize with as the day moves along. The same person, possibly as part of a core group of participants, can help the facilitator plan the event.

4. Pick a champion to nurture the group’s vision

Referring to research contained in the white paper, Josie Plaut also emphasizes the need for a champion to support the kind of integrative design process found in workshops. “You need someone who is a champion on the design side,” she says, to ensure the integrative workshop process is supported and its value maximized. “Preferably you need the owner and the architect. If either one is opposed, then nothing’s going to happen,” but she says you can still move forward with having an integrative process if one is ambivalent about it.

Having a champion in the project leadership provides four functions:

- Initiates an aspirational vision, including design goals, performance goals, and goals for how the team will work together

- Clearly prioritizes integrative process for the team, possibly including contract structures (like integrated project delivery) and support of facilitated workshops

- Gives permission to take calculated risks, including unfamiliar technologies, strategies, and materials that might deviate from standard industry practice but can be effectively explored in an integrative process

- Holds the team accountable with owner-created design guidelines, performance contracts, or commitment to earning third-party certification

5. Prevent design by committee

A common fear of an integrative design process bolstered by charrettes is “design by committee,” where nonprofessionals obstruct smart design decisions in the name of providing input. That’s not an unfounded fear, but it’s an avoidable one, according to facilitators we spoke with for this article.

“Architects have a wide range of communication skills, which includes translation,” says Jennifer Preston. If occupants say they want a particular type of window in the façade, “it’s our job as design professionals to understand what is the intent behind that statement.” The occupant might be envisioning a certain shape or size of window, but through careful listening, we learn that what they really want is a comfortable place in the sun. To create the right kind of space, the designer considers a multitude of things—view, solar orientation, context in the plan. To get the kind of input you need from stakeholders, ask open-ended questions. Discovery happens there, says Preston.

Z Smith, AIA, principal at Eskew+Dumez+Ripple, suggests that one way to frame this conversation is around values. On a church project, he says, his firm didn’t ask the church committee what they wanted the building to look like. They provided a variety of images for inspiration, and talked about qualities of light and space. That allowed the client to articulate, says Smith, that they “want a space that’s ordered in this way, and connected to the outdoors in this way. It was not about them designing the building but articulating the qualities of value to them. We could hold onto the things we were expert at, and they could hold onto what was of value to them.”

In workshops involving stakeholders who don’t know the design and construction process, make sure you’re clear about who’s providing input and who’s making final decisions. Integrative workshops typically have a democratic feel, but don’t let that mask hierarchy in decision-making. People are generally okay with this if it’s explicit and acknowledged.

6. Plan well, but go with the flow

Preparing for a workshop means a “combination of having a plan and knowing ahead of time that you’re not going to follow it,” says Moshe Cohen, of The Negotiating Table. “You have to be responsive to what’s really going on in the room.”

Cohen, a negotiating specialist who does training and facilitation, explains that his background is in mediation. “In mediation, you never know where things are going. People come in complaining about one thing, and by the end you realize it’s about something completely different than what you thought.”

Workshops are not that different. “When I facilitate, I don’t know where things are going to go. And I don’t know they are going to go well.”

“The one thing participants won’t tolerate is any sense that the facilitator is bullshitting them or is not transparent with them,” says Cohen. He tries to project a sense of openness and competence: “I don’t know everything, but we’re figuring this out. You need to give them this sense that no matter how chaotic things are now, everything is going to be all right. That’s really reassuring.”

You also have to know when something’s not working. “I’ve undertaken activities that totally belly-flop. You’ve got to say to the group, ‘What do you think is not working, and how can we fix it?’ You can’t have any ego up there. You’re serving the process and the group.”

Setting a Schedule and Agenda for Success

What should be on the agenda?

Phaedra Svec, associate at BNIM, sometimes gets asked by a colleague to share her “best agenda.” She says, “As if that’s the magic! Even if you tell the same story over and over again, you tell it differently depending on your audience. The same is true to plan or design a good meeting agenda. And it’s incredibly undervalued as a skill.”

“The agenda process is a design process,” says Jennifer Preston. “The consideration that goes into the how, who, and why of meeting setup is critical. And it takes thought and input and discussion.” She distinguishes that kind of exercise from burdening a workshop with an over-precise agenda where problems are listed and solutions produced. If the agenda is well formed, “the meeting can be what the meeting needs to be.”

7. Understand their greatest hopes and fears

The degree of preparation for a single workshop varies depending on the facilitator and the goals of the event. A good rule of thumb, however, is to spend at least as much time preparing as the workshop will take: a day or more for a day-long workshop, for example.

The degree of preparation for a single workshop varies depending on the facilitator and the goals of the event. A good rule of thumb, however, is to spend at least as much time preparing as the workshop will take: a day or more for a day-long workshop, for example.

One common way to prepare is to interview participants about the coming workshop and what they want to get from it. This may even take the form of a meeting of its own with a subset of the workshop’s participants.

Asking a client for their highest hopes and their greatest fears for a project is one approach that Lisa Petterson uses to figure out what’s really on their minds. Fears might be in red and hopes in green. You write down everything and then ask people to vote on their strongest sentiments. This approach worked well on a project that involved a renovation of an existing building and a large addition. “One of the fears was [that] there wasn’t going to be enough money to renovate the entire building, and there was going to be hodge-podge” left over, she says. “It would have been easy to focus all the attention on the new building” in the workshop, she says, but because that concern had been aired, they knew they had to dedicate time to problems they wanted to fix in the renovation.

8. Ask them what success looks like

Numerous facilitators emphasize the utility of a shared understanding of what success looks like. To plow a straight line an a field, Moshe Cohen says, “You look at a tree on the other side and never stop looking at the tree. That’s what guides you. This direction you’re going in, how consistent is it with that tree?”

Cohen credits Interaction Associates with a useful framework for that: desired outcome. Outcomes are nouns. Cohen likes to ask, if the workshop is successful, “What do we have in our hands at the end?” Or, “Let’s pretend the session has started, it’s ended, it was wonderful. What’s different?”

It can take asking a few times to get to the heart of the matter. The group might say that they want to discuss key issues—which isn’t yet a clear outcome. Cohen will ask, “Let’s pretend we had the discussion. What do we have in our hands at the end that makes it worth having?”

“By the end of that initial conversation, you have a set of desired outcomes, and maybe you prioritize them,” says Cohen. “Let’s pretend we don’t have time for all them; which of these do we really want to have in hand?”

To bring the agenda to life, incorporate outcomes into it. Rather than blocking off time for “daylighting,” dedicate time to “identify, for each major occupancy, five ideas for how daylighting could contribute to occupant experience and energy savings.”

9. Give the audience the reins

Depending on the workshop, you could establish trust, put specific topics on the agenda, and guide specific discussion topics in one fell swoop.

Richard Crespin of CollaborateUp is facilitating a series of workshops, through a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, to look at how businesses can play more of a role in community health. With 200 people sitting around tables, and a slate of speakers on a dais, Crespin gives the audience the first word. He asks the people at tables to introduce themselves to each other and name what they think is the number-one barrier to a healthier city. Each table confers and agrees on one item, then shares it with the whole room, generating about 20 items. Then every single speaker has to get up and speak to one of those topics. The rest of the workshop goes back and forth between the stage and the small groups.

Crespin likes the format for two reasons:

- Giving the audience the first word: “They are in control. They are driving the agenda.”

- Clear direction to speakers: “Left to their own devices, they might have spoken right past these issues.” They don’t need to make things up, and they don’t have any reason to waste time formulating bland speeches.

The workshops wrap up with commitments—something each attendee is willing to do within a short period of time. “They are now part of something larger than themselves,” says Crespin.

10. Don’t make people miserable

Don’t get too focused on a narrow definition of success, says Moshe Cohen. “It’s nice to have the results. But there are miserable processes to go through, [and] there are more fun processes to go through.” He says, “I want to ask them, ‘What do you want this conversation to look like?’”

Most people don’t want to sit brainstorming for eight hours straight, if they can even last that long without getting bored, disengaged, or tired. But different groups have different priorities. Do they want to move around? Do they want small chunks? Do they want to break things up with pecha-kucha style presentations? Different groups will name different preferences that can be used in designing a workshop.

Of course, keep in mind that the facilitator, as with the role of the architect discussed earlier, is a translator. Look for what the group wants the day to feel like, not necessarily what the specific activities are.

11. Give them a night to sleep on it

Even if it’s two half-days, being able to include a night’s sleep in the middle of a workshop is invaluable, says Clark Brockman. The logistics sometimes make it impractical, he says, but when it works, “It’s remarkable what happens overnight.”

Brockman likes to “make sure that in the first day you get all of the hairy, difficult issues laid out. You really want people to go to bed with their heads filled with a thorough and honest view of the complexity of the project.” According to Brockman, the group knits together as a functioning team on day one, and on day two, the solutions “are just better.”

You have to be okay leaving things unresolved, “which can be pretty uncomfortable,” cautions Brockman. He recalls a workshop on materials and health that was particularly successful at laying out, on the first day, all the reasons why the problem was hard and could never be solved. Had he taken things too far? The second day, “Everyone came back ready to work, and a lot of interesting things happened.”

12. Start on time; end early

Fill the mornings and go easy in the afternoons, says Ralph DiNola, CEO of the New Buildings Institute, who says he’s gone from doing eight-hour sessions to preferring five or six hours. Once you decide you’re not going to push on to 5 p.m., the day typically breaks down into three chunks (with breaks between):

- First morning session

- Second morning session

- Early afternoon session

“After that, it’s hard to do anything,” says DiNola, based on his experience with dozens of workshops.

13. When you’re short on time

Ralph DiNola has been a part of five-day charrettes and half-day ones. If you’re pressed for time, what should you focus on?

He breaks it into the following hierarchy: you start with a vision or mission statement. In order to achieve that vision, what are the goals? (They should be measurable.) Then get down to the core strategies that will help you achieve those goals.

“The tactical part,” he says, “the action plan, is something you can outline and continue to work on later with a more thorough work plan.”

How to Set the Table—For the Right Group of People

Who you invite, how you frame the conversation, and even the food you serve, can all be design opportunities to bring you closer to your goals.

14. Run a diversity check

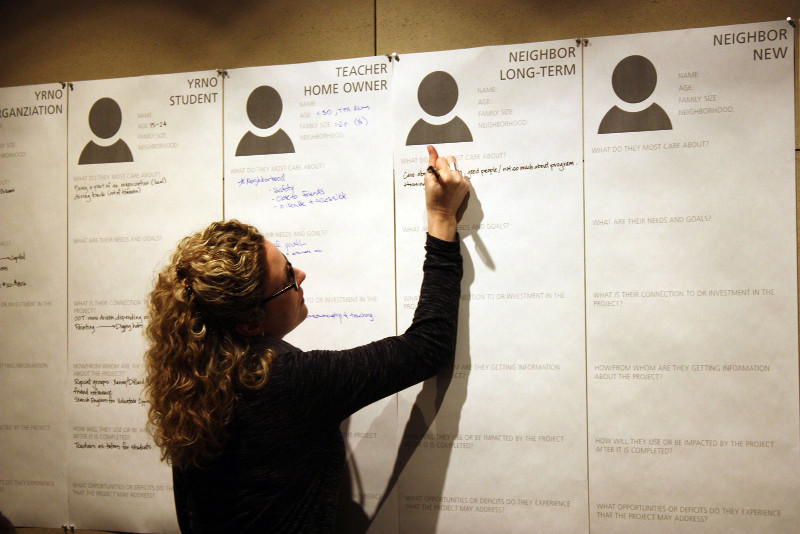

One of Phaedra Svec’s approaches to workshop design is place-centered. She’ll ask herself, “What do we need to know about this place and all the people who have a stake in this place?” That leads to a lot of thought about who is invited, with a focus on disciplinary diversity.

One of Phaedra Svec’s approaches to workshop design is place-centered. She’ll ask herself, “What do we need to know about this place and all the people who have a stake in this place?” That leads to a lot of thought about who is invited, with a focus on disciplinary diversity.

For an early-phase interdisciplinary design workshop, Svec wants to have—to name a few—an investor or someone who’s focused on finances; a facility manager; people who are responsible for the program; and people who are thinking about ecology and water. If it’s a university project, she wants someone from the greater community. If it’s an office building, someone from the neighborhood.

What about the designers? Svec wants “co-creators who are not just designing sculptures that are buildings, but people who are designing the experience that you’re going to have there.”

For a net-zero-water project, Svec wants “everybody who has a stake in water in that system,” from wastewater plant engineers to irrigation system designers to the plumbing engineer to a landscape architect or engineer who’s an expert in living systems.

Take the right people and the right workshop activities, “and then somehow because you’re all there together, you have enough of the little pieces of what you need to make the whole solution. And it’s really kind of magic,” says Svec.

15. Let wallflowers bloom

Awareness of differences in how introverts and extroverts contribute to a workshop, and how to support everyone’s voice, was a common theme from experts we spoke to for this article.

“I mix up the process,” says Moshe Cohen. “There might be introverts who won’t say a word in a large group, but get them into small groups, and they are really comfortable.” Change the structure from large groups to small groups to pairs. A facilitator can float around and ask questions of specific individuals to bring them into the conversation.

Mixing in reflective writing and speaking also tends to give everyone an opportunity to contribute. Before a group discussion, pose a question and ask everyone to write a few ideas in response. Then discuss those with your neighbor, and then discuss them with the larger group. That progression allows everyone time to organize their thoughts.

16. Gain value from disagreeable people

“You as a facilitator have to be there to support even the most vocal, argumentative voices in the room,” says Moshe Cohen. “You don’t want to alienate these folks who sit in the back smoldering and looking for ways to sabotage” the day.

Their interests might not be shared by others, but you have to work with what’s there, says Cohen. Either individually or in the group, get them to talk about their interests—which might not be what you think. The fewer assumptions you can make about where someone is coming from, the better. And often, when someone feels heard and sees the larger purpose of the room, they will cooperate more fully.

Someone who disagrees with the rest of the room might have a critical point. What if the room is ready to move on to a new topic, but one person isn’t ready to let it go? Ask them why, and write out their interests. Then, negotiate a process to move forward that helps move the group toward success.

17. Inspire new thinking with an outside expert

Bringing an expert into a workshop who isn’t attached to the project can catalyze fresh thinking. On one project, a highly controlled laboratory building for nanotechnology research, Wilson Architects brought in engineer Peter Rumsey to a number of early workshops. Jacob Werner, AIA, director of sustainable design at Wilson, says that the team invited Rumsey because of his experience in regions outside of the project team’s core experience, and because of his sense of what is theoretically possible as well as what is sensible to pursue.

The project’s programming puts it on the extreme end of energy use intensity, according to Werner, at about 1,000 kBtu/ft2. “Little things that might not matter as much” on a smaller building, “like coefficient of drag on the ductwork, can result in huge energy savings,” says Werner. Spurred on by Rumsey, the team looked at engineering the ductwork to reduce the static pressure in the system. The bigger ductwork will require more height but could make a huge difference in energy use.

18. Set ground rules to maintain focus

Setting ground rules for participants is second nature for experienced facilitators. Laying out such rules explicitly isn’t always necessary, but when they do need to be enforced, it’s better to have had the expectation out in the open.

Great ground rules generally follow common themes, though they vary depending on the workshop activity. “Rules for brainstorming are different from rules for problem-solving or prioritizing or coming to consensus on a direction,” points out Nadav Malin, president of BuildingGreen and an experienced facilitator.

The one rule Malin finds the most common application for across workshop activities is “one idea at a time.” When speaking (or facilitating), finish one topic before moving on to the next. That way, everyone knows what the current topic is and can develop it together. When multiple ideas are on the table, the group loses focus.

Other rules that Malin draws on (crediting the facilitator Robert Leaver), especially for values-alignment exercises, include:

- Speak from your heart.

- Listen with rapture.

- Speak for 30 seconds.

- Make sure everyone has had a chance to weigh in on a topic before moving on—especially those who might be inclined to hold back, whether due to personality or internal politics.

Malin’s favorite rules for brainstorming, which can apply to other situations, include:

- Never respond or react to others’ ideas while brainstorming.

- No ideas are bad ideas.

- Name it; don’t explain it (at least not for more than a few seconds).

The latter can feel like a tight constraint, but when enforced in practice, it helps overcome a couple of tendencies: to say something once and then explain it or repeat it in different words; and to move on to a related idea.

19. To enable risk-taking, create a safe space

A term sometimes used to describe the space created by ground rules like these is “safe.” According to the Institute for the Built Environment, every project it studied for its white paper on collaboration that had an ineffective process had one trait in common: a lack of safety and opportunity to share ideas.

A term sometimes used to describe the space created by ground rules like these is “safe.” According to the Institute for the Built Environment, every project it studied for its white paper on collaboration that had an ineffective process had one trait in common: a lack of safety and opportunity to share ideas.

The paper describes safety as an “inclusive environment that fosters participation and a willingness to share ideas and ask questions.”

Ground rules like those above, when enforced tactfully, can go a long way. Many people will only become fully invested in a workshop and actively participate after they’ve assessed that it’s emotionally safe—that they won’t be ignored or be ridiculed for an idea. Establishing and reinforcing that environment is a primary function of good facilitation. It’s done by amplifying a comment that the group might otherwise have devalued because it didn’t come from someone in a position of power. Or it can come by respectfully interrupting someone who is taking the group off track. The latter is especially difficult but shows a commitment to the process and a focus on the entire group. It’s also about what you don’t do: talk down to someone or laugh at their expense.

To set ground rules that fit your audience and speak to them in their language, listen carefully and be flexible. Facilitators often take risks in bringing their own language and methods to a group they don’t know that well. Talking about “safe” spaces isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, for example. “Trust” could be a better synonym for some audiences. Pushing people outside of their comfort zones can be constructive, but you don’t want to lose half the room simply because your language doesn’t fit their culture.

20. Feed them. Well.

Food and setting are essential parts of meeting design, says Jennifer Preston, who considers hosting to be part of the architect’s role, “making sure that everybody feels welcome.”

It started with the simple observation that design staff show up to lunch-and-learns. Now, “in every meeting where I have brought a version of nourishment to it, there’s been an exhalation,” Preston says, which she claims can create room for discovery. With one client, her firm was leading an intensive four-hour workshop to evaluate the possible alignment of LEED, the WELL Building Standard, Passivhaus, and the Living Building Challenge on a high-rise residential project.

It was lunchtime.

“We knew that health and wellness were highly valued by this client, and for us too,” Preston said. “We were very particular about the kind of food we brought in,” which included simple, colorful, whole foods. In general, she aims for supporting collegiality with something more like a family meal than a corporate boxed lunch. Before a meeting, Preston unwraps and breaks up chocolate bars; they’re a go-to item for keeping energy up, but no one wants to deal with that awkward crinkling sound mid-meeting. She pre-peels oranges and thinks through the setting of the table with paper, pens, and other items. “Everything is a design opportunity,” she notes.

The meeting concluded on an encouraging note and has led to ongoing dialogue about the project goals, including wellness. “I believe that started with nourishment,” she says.

Stretch the Group’s Vision to Maximum Benefit

When I picture a design charrette, I see architects huddled together, drafting, mapping programs, and detailing wall sections. I picture plans pinned on the walls.

When it comes to the heart of a workshop, drafting can be an essential activity. But as we’ve been exploring throughout this article, the most successful workshops are a design exercise from their conception all the way through reporting out. They allow for deep input, conversations, and team building. Let the sketching and other specific work of design occur as an organic result of this broader setting.

21. Small talk is a big deal

“Build into the day some time at the beginning that is more of an informal conversation time,” says Cohen. “Preferably feed people. While they’re eating, walk around as the facilitator. Go and have personal conversations not about the substance of what they are there to do, but people’s lives, their commutes. Later on, when you need to connect on substance, the ice has been broken.”

While that may seem like common-sense advice, how many meetings, workshops, or presentations have you been to where the facilitator is in front of the room fiddling with their equipment while people are gathering and eating?

Nadav Malin notes that this skill was part of what made the late Gail Lindsey, FAIA, exceptional. “By the time a meeting started, she had found a common experience or common friend with nearly everyone in the room.”

22. Build the group’s trust with an early win

There are a lot of ways a facilitated workshop can go off-course, says Moshe Cohen. Trust among the group and with the facilitator is critical to bridging rough areas. He advises winning the trust of the group early in the process.

“Very often, I will get them going with some activity that gives them the sense that I know what I’m doing,” says Cohen. Since defining success is also key, an early discussion is likely to be: “What does success look like for today?”

“There is no way to get that wrong,” he says. “The way you conduct yourself in that first discussion says a lot about how you’re going to function as a facilitator the rest of the day. You win some trust.”

23. Support iteration: Show your work

Once Phaedra Svec has the right people in the room, she wants them to be transparent with each other.

“You want them to show their work and have their assumptions shown in a common spreadsheet or up on the walls,” she says. If you’re not doing that, she warns, rather than iterating through progressively more appropriate solutions, you’ll end up in a circular conversation. Svec also notes, six months from now when you’re still tweaking your water usage numbers and how that affects the constructed wetland, you need to be able to see what everyone contributed and what they were assuming.

24. To save time, get to the heart of sticking points

With a current government client, Phaedra Svec was pushing them to consider drinking rainwater.

Why didn’t they want to? “Rainwater is dirty, and you can’t control it.”

Why can’t you? “There’s bird poop.”

There is a first flush, and then there’s filtration, so… why? “There’s the city water; we know what’s in it.”

Do you really know what’s in the city water?

By asking a lot of questions, Svec says (“usually it’s about five layers deep”), they found that the client could see the possibilities of consuming onsite rainwater, but is concerned about becoming responsible for water quality and possible health repercussions. It’s not clear whether or how the project will surmount that objection, but at least they’ve identified the core problem. That could become a design challenge, or it could become a constraint, but in any case they aren’t wasting time talking about water filtration options.

25. Make your research relatable

Presenting research on the project site and setting that’s done in the weeks before a workshop is important to Rand Ekman, AIA, chief sustainability officer at HKS. “Mechanical people need to be able to express a ventilation perspective. Landscape people need to talk about habitat and water. The owner needs to talk about the values that are driving the project,” he says. “It all paints a picture of what matters for that place.”

Presenting research on the project site and setting that’s done in the weeks before a workshop is important to Rand Ekman, AIA, chief sustainability officer at HKS. “Mechanical people need to be able to express a ventilation perspective. Landscape people need to talk about habitat and water. The owner needs to talk about the values that are driving the project,” he says. “It all paints a picture of what matters for that place.”

Ekman likes to present sustainability-related topics in a way that relates clearly to the place of the project and the values of the people involved. For example, rather than talking about global warming in abstract terms, he relates it to the U.S. Heat Wave Index and its effect on asthma rates in the area.

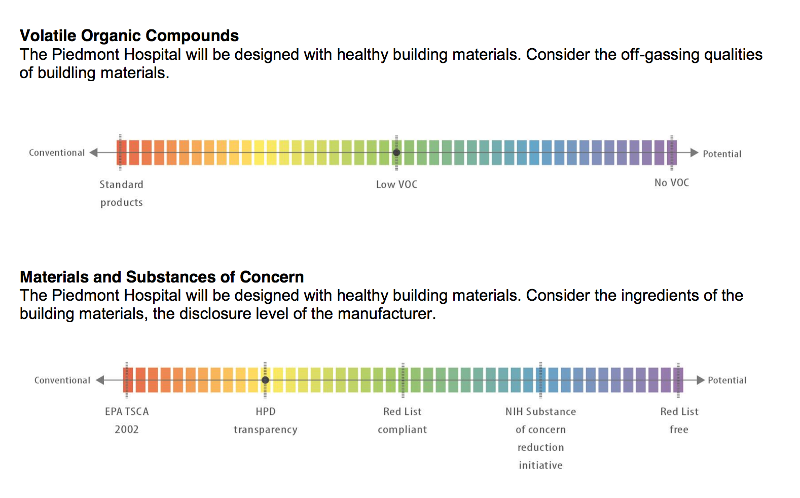

Ekman uses all that research as setup for activities where stakeholders identify exactly where they want to fall on a scale of options for topics like energy efficiency, ventilation effectiveness, and material health.

26. Invite nature into your brain

Connecting to nature in whatever setting you’re in is useful on a number of levels, says Phaedra Svec. At one charrette, the group was working next to a green roof planted with prairie plants. After working through the morning, she asked people to go outside, close their eyes and take a deep breath and engage their senses. The instructions: take in the sounds and smells, feel the sun or the shade or the breeze, and then open your eyes and find something that’s living.

The participants were standing on a green roof situated in a dense urban space. “There was a lot of stuff that wasn’t alive,” Svec said. She didn’t think they would look any further than the roof. They did, scanning the horizon for trees and making other discoveries. One person looked up a hill at some patches of continuous habitat, and saw the rooftop as another patch, and the building they were designing somewhere in the middle. “We determined that while Kansas City [Missouri] has a whole monarch butterfly waystation program in place, nobody had considered how to do that downtown. We saw the opportunity and incorporated it into the project.”

While that exercise had a very specific impact on the project, the change in mindset is the real object, she says. “People get into that place of being a little bit more mindful,” Svec notes. “They set aside some of their anxiety about being with strangers. They tap into the creative part of their brain.” Being able to draw on that energy throughout the day is important.

Even if you’re stuck in a windowless conference room, you can always have a group close their eyes and visit a place that was alive for them when they were children. “Everybody has an answer for that question,” says Svec. And “you get to hear something about that person that you wouldn’t have known otherwise.”

27. Kill groupthink with a pre-mortem

According to Richard Crespin, the “pre-mortem” meeting, for anticipating problems rather than waiting till they’ve happened, was developed after the Challenger disaster. After the Space Shuttle exploded during launch in 1986, the public learned that engineers had recognized a significant risk in proceeding with the launch; they had voiced those concerns but were ignored.

“People behave differently in groups than they do as individuals,” says Crespin. “Part of being in the group is abiding by certain group norms,” which in the case of the shuttle engineers was a mentality called “go fever.” In the pre-mortem, Crespin says, “Let’s step back and look at all the ways this thing could fail. How can we mitigate or avoid these things?” An exercise like this makes it part of the meeting norm to ask challenging questions.

28. Teach a model to organize thinking

Moshe Cohen blends teaching into facilitation—and not necessarily on subjects that directly relate to the field in question. “If the group is talking about a specific subject where I think I can help them organize their thinking by relating it to a relevant theoretical model, I’ll throw it in there,” he says. “It helps people organize how they think.”

For example, if a group is dissatisfied with some aspect of what they’re designing, Cohen might introduce them to Kurt Lewin’s force-field analysis, a framework that looks at how “helping forces” or “hindering forces” are driving movement toward or away from a goal. He’ll then ask the group how they could apply it this to the situation.

29. For painless brainstorms, note and vote

Have you ever been in a brainstorming session that felt like it was moving too slowly or was bogged down by spending too much time on less effective solutions? At BuildingGreen, we sometimes combat these tendencies with the “note and vote” approach, which was popularized by Google Ventures.

Here’s the structure:

- Everyone gets paper, a pen, and is asked to brainstorm as many ideas as possible. No one but you will see this list, so don’t self-censor. [5 to 10 minutes]

- Pick one to three favorites from your list. These are the items you’ll share with the group. (In a large group, you might first share these with one or two other people and winnow your list down further before sharing with the whole room.) [2 minutes]

- Go around and share your top ideas, with one person recording them on a whiteboard. There’s no discussion or feedback yet. [5 to 10 minutes]

- Take some time to contemplate and pick a favorite idea. Write it down. [2 minutes]

- Reveal your votes and note them with a dot on the whiteboard. [3 minutes]

In “classic” note and vote, there is a decider who picks the idea or ideas that the team will go with. In a workshop environment, you could open it up to discussion. Should an unpopular idea be considered? If we accept the favorite idea, how do we build on it?

Try note-and-vote the next time you need to generate new ideas or choose an option.

30. Close your eyes to see better

Ralph DiNola often does a “visioning” exercise right after introductions. “It may feel a little touchy-feely,” he says, but you have people close their eyes. “It’s opening day; the project is completed. There’s a celebration. You arrive, walk up, what do you see? What’s outside? What does it feel like? What do you smell?”

DiNola asks participants to visualize all of this, remember key features, and then write those things down before reporting out. “It’s a powerful way of having people have a vision of the shared goal.”

31. Use time travel

Ralph DiNola also likes extending visioning to the far past or future. Design an exercise for a project that might look and feel like the one you’re working on but is outrageously different in some way. Change some parameters so that “All of our preconceived notions don’t exist any more,” he says, like that plumbing or electricity as we know it don’t exist. “Set them loose on it and make it a competition,” DiNola advises. “That frees people up to be super-creative and outrageous.”

“The design solutions are really amazing, and when you then get into the present day charrette, that thinking shows up,” he says. One workshop envisioned using algae as a natural pump for future water systems. Back in the present, that translated to concepts for integrating the building’s water systems as a visual feature.

Another way to spur imaginative thinking is simply to set ambitious goals as thought experiments. For some projects, that might be Living Building Challenge certification. The trick might be finding the goal that’s exciting for the group but not too intimidating. If net-zero energy feels out of the question for an entire project, maybe there’s a wing that could be net-zero. And if that’s inspiring and gets traction, perhaps it can grow.

32. Show you’ve heard them

Whether or not your idea gets used, you want to know that it was heard. And when there is confidence that ideas are being heard, more ideas—and more radical ideas—tend to follow. Generating ideas and giving them air is one point of the workshop, but so is giving participants a sense of ownership and investment. For that, too, it’s essential that everyone feel heard.

Whether or not your idea gets used, you want to know that it was heard. And when there is confidence that ideas are being heard, more ideas—and more radical ideas—tend to follow. Generating ideas and giving them air is one point of the workshop, but so is giving participants a sense of ownership and investment. For that, too, it’s essential that everyone feel heard.

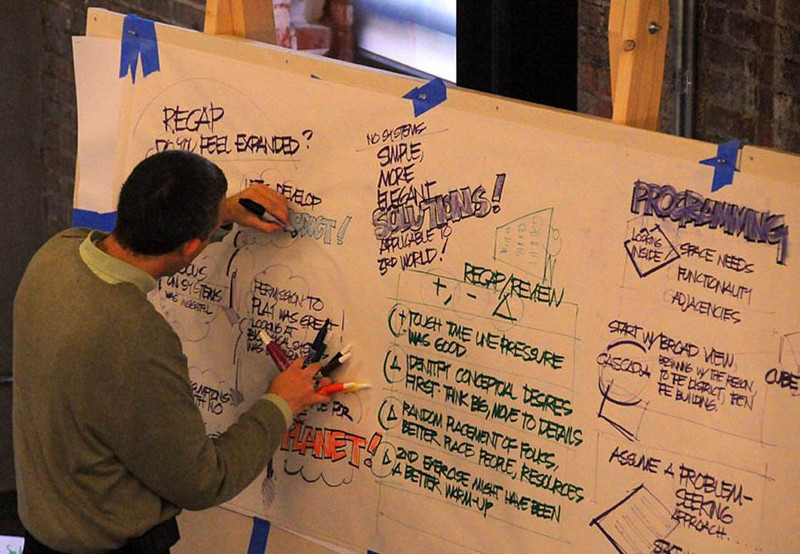

Lisa Petterson likes to employ really easy design tools in workshops, like wooden blocks and colored pieces of cardboard that represent difference pieces of the program. Taking notes on whiteboards or flipcharts is standard practice, of course, and some workshops hire graphic artists switching nimbly between five different colored markers to capture ideas as the group works.

Whatever you do, “People just want to feel like their thoughts are captured,” says Petterson. If you’re taking photos of flipcharts or models, a Polaroid camera gives a physical sense that something has been recorded. If you’re going digital, Petterson says that having a computer in the room where photos are uploaded gives a real sense that the ideas haven’t disappeared.

33. End with a question, not an answer

If you’re doing a multi-day workshop, how do you get the most out of that sleep cycle, as well as relaxed evening time?

Phaedra Svec suggests formulating a specific question that invites participants to reflect on the day, and stretch a bit. She’s typically spontaneous about it, but an example might be, “Imagine that you’re a young student coming to this site for a field trip. What kind of experience do you want to have?” Depending on the workshop’s topic, she might ask a question that hasn’t been discussed yet but that isn’t too heavy, like “Is there a place for pollinators on the site?”

The question does a couple things, observes Svec. It displaces busy-work, like rerunning calculations after dinner, that would get in the way of reflection. It also gives people a sense that they’ll be returning to something fun in the morning. It also takes away anxiety about not knowing what you’re going to be expected to contribute the next day.

Extending the Value

Do you have time for all this? If you think you don’t, that’s a good sign you do.

34. Know the price and what it buys

Z Smith, while lamenting that some projects move on timeframes that make well planned and well attended workshops hard to do, says that they typically save time overall.

Z Smith, while lamenting that some projects move on timeframes that make well planned and well attended workshops hard to do, says that they typically save time overall.

“This notion that you don’t have time is true if all the different players are completely disempowered,” he explains. If the architect or the owner can move forward with a project with little input, the project won’t be as good without a design workshop, though it might move more quickly. “But in the real world, there are lots of possible veto mechanisms.”

A typical example is a project where the design team gets relatively far along and tries to win over support for a project with what Smith calls the “ta da!” effect: just give them a beautiful design, and everyone will come on board. In practice, people who haven’t bought in can and will organize to stop the project. Another four months or more get added to the schedule. “The people who think they don’t have time to do this have to back up and start again.”

The financial case is similar. Clark Brockman describes a typical workshop where the client “walks into the room and they see 15 or 16 people, most of whom are the most senior people in the firm. You can just imagine certain clients that start to tally; this meeting is clocking in at $6,000 per hour.” To get them to forget about that, Brockman says, “The goal is to meet or exceed the value that would have been achieved if those people were working for the client on different things. Shift their thinking and arrive at a solution they wouldn’t have gotten to” if they weren’t there. Doing that is a bit unpredictable in that you never know where the added value will come from, but it’s completely replicable with effective facilitation.

35. Reports: Keep them short (and cheap)

Ralph DiNola talks about a project on which a developer was rehabilitating a historic property to lease to a university. The developer was respected for historic work but new to LEED and also new to the charrette process.

In a post-mortem review of the successful project, DiNola was shocked when the developer seemed to turn his back on the charrette, saying, “I don’t know if I would do that again.” DiNola thought that the workshop had transformed the project and set it on a positive track. Back at his office, he pulled up the charrette report, which described key features of the project—all of which were realized when it was designed and built. DiNola sent the report to the developer with a note. The developer replied with an apology in which he affirmed the value of writing down goals, and how the charrette had enabled that. DiNola notes that, like a roadmap, a report shouldn’t sit on the shelf. “Come back to it and check on it.”

Josie Plaut says that long and fancy reports have helped make some projects feel that they can’t afford workshops. “It’s the process itself which is the value-add and not the report,” she contends, noting that the Institute for the Built Environment now spends much less time (and fee) on creating a report.

36. Continue the transformation, from project to organization

A good workshop will produce a high-functioning team with a unified understanding of its vision and likely strategies. “You know the project will be better,” says Clark Brockman.

Ralph DiNola agrees that integrated workshops are really about building effective teams. He asks, “How are you going to change what their process is to deliver on that not just once but many times?” Once an organization has some experience with workshops, DiNola suggests finding new areas to apply them.

At one corporation, he says, the group was so pleased with charrettes done for individual building projects that they did a charrette just focused on commissioning. Commissioning agents were running into roadblocks and finding that teams weren’t coordinated around their work. The workshop focused on solving those problems as a team. DiNola has done lots of workshops for design and construction projects; he sees value in doing more at the organizational level.

Wrapping Up

If this article were a workshop, I’d want to check in now about your experience. Did you get a couple ideas to apply to your next event? Are you inspired to bring a more integrative process to your next major project meeting?

If so, please leave a comment with your thoughts.