From an environmental standpoint, the low-slope roofing on commercial and industrial buildings is a big problem. (“Low-slope” roofing is often incorrectly called

flat roofing—it nearly always has a slight pitch). For starters, there is a lot of it. No one in the industry seems to know how much low-slope roofing exists in the United States, but back-of-the-envelope calculations by

EBN indicate that the nation’s 4.8 million

commercial buildings (not including industrial or agricultural buildings) have on the order of 1,400 square miles (3,600 km2) of roofing (mostly low-slope), an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. In the U.S., we spend $13 billion dollars a year on commercial roofing (1996 data), 75% of that on reroofing and 25% on new construction.

Low-slope roofing has an average life of about 20 years—often considerably less. Some studies have indicated an average life of only 12 years for the most common roofing types. During reroofing, conventional practice is not only to remove and landfill the old roofing, but also trash the rigid insulation that is usually an integral part of the roofing—and can account for 75% of the volume of roofing waste. Roofing waste is a significant portion of the construction and demolition waste, though detailed statistics are not available.

Other significant environmental impacts of low-slope roofing include the pollutants released from hot-melt asphalt built-up roofing systems, life-cycle concerns about materials used in manufacturing or disposing of the roofing, and the tremendous building damage resulting from failed roofs.

While the ideal low-slope roofing materials and systems may not exist yet, we can do a lot better, from an environmental standpoint, than conventional practice today. This article provides an overview of low-slope roofing and addresses options for reducing environmental impacts of these roofs. We look at both some tried-and-true options for creating environmentally better roofs, such as the protected-membrane system, and some newer ideas, such as the green (planted) roofs that are catching on in Europe.

A Brief History of Low-Slope Roofing

Prior to the late 1800s, most roofs were fairly steeply pitched. A steep roof (pitch greater than about 3:12) has numerous advantages: sheds rain easily; is highly forgiving; doesn’t have to be fully watertight; is generally able to vent water vapor and thus release trapped moisture; and can be quite inexpensive. Overlapping wood shakes, slate shingles, metal panels, even bundled grass (thatch) can function very effectively as long as the roof is steep enough that rain will flow off before wind or other forces can drive it through the roofing, causing leaks.

As the industrial revolution got under way in the mid-1800s, however, it made sense to build larger buildings. The wider the building, the more expensive it is to build a pitched roof needed to shed rain effectively. By keeping the roof flat—or essentially flat with a very low slope—cost and wasted space could be significantly reduced. The challenge was (and is) that a low-slope roof has to be

waterproof—as opposed to merely being able to shed rain. A continuous, monolithic membrane is needed to keep rainwater out.

The first low-slope roof membranes appeared in the 1840s. Large square sheets of sheathing paper used in boat building were treated with a mixture of pine tar and pine pitch and laid out on the roof between layers of a bitumen made from coal tar (then a waste product from coal gas production, now a by-product of coking, a process in steel making). Coal tar soon replaced the pine tar as the saturant, because it was more fluid. Then

rolls of felt replaced the square sheets that had to be hand-dipped in saturant. Multiple layers could be laid quickly, providing a more durable roof surface. The built-up roof was born.

By the end of the 1800s, asphalt began to appear as a competitor to coal tar pitch, both as felt saturant and mopping bitumen. (Asphalt is the residue remaining after higher-value products are extracted from petroleum.) Asphalt was both more versatile than coal tar—with a wider range of viscosities—and less expensive. Paper (organic) felts began to be challenged by asbestos felts in the 1920s, then fiberglass felts after World War II. The multi-ply, hot-mopped, built-up roofing (BUR) system, with a few material variations, held a virtual monopoly on low-slope roofing until the 1960s, when modified bitumen and single-ply roofing membranes appeared.

The most common of today’s mix of low-slope roofing types can be divided into three broad (and sometimes overlapping) categories: built-up roofing; modified bitumen; and single-ply.

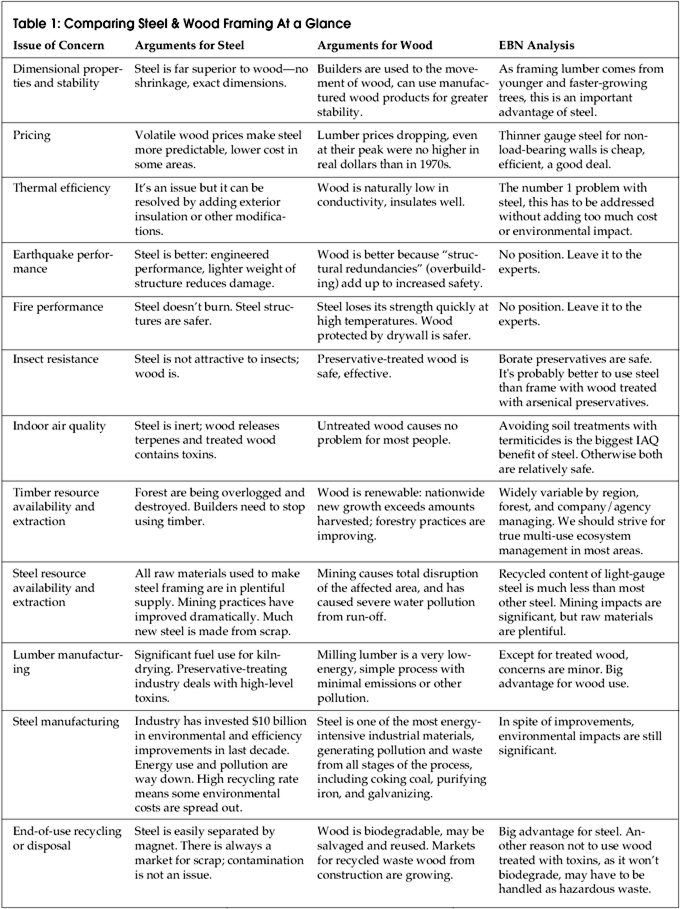

These are described very briefly below, including discussion of environmental characteristics. Low-slope metal roofing is addressed later. Other options, such as spray polyurethane foam, are not covered in this article. The table at left shows the market share of different low-slope roofing materials in the U.S.

Built-Up Roofing

Built-up roofing (BUR) is the oldest type of low-slope commercial roofing. While it has gradually lost market share to newer, more advanced materials, BUR still represents nearly a quarter of the commercial roofing industry. (In some areas, such as Chicago, BUR is actually making a comeback, according to roofing consultant Steve Shull, of e-Roof, Inc., following disenchantment with some of the newer systems.) Typically, four plies of felt are applied between coatings of asphalt or coal-tar bitumen heated to between 400°F and 500°F (205°C-260°C). The hot bitumen is generally mopped onto the roof surface by hand. The top coating of bitumen is the

flood coat, and aggregate is embedded in it before it cools. The aggregate provides protection from intense sunlight, hail, and foot traffic. It also increases the roof’s reflectivity to some extent, improves fire resistance, and helps resist wind uplift. With insulated roof assemblies, BUR is generally adhered to the insulation.

From an environmental standpoint, heating and spreading the hot-melt bitumen releases VOCs and particulates, which are responsible for the strong smell of asphalt during roofing. In addition to volatization of the bitumen, a standard 450-gallon (1,700 l) kettle used for heating bitumen on the roof uses about 25 gallons (95 l) of propane or kerosene per day, adding to the emissions. BUR roofing has only moderate durability. The industry rule-of-thumb is that each ply provides about five years of expected roof life—thus for a four-ply roof a 20-year life is expected. BUR becomes brittle at low temperature and cannot expand readily to accommodate movement of the building. During reroofing, both insulation and BUR membrane are typically landfilled. The weight of the BUR membrane is generally about 2-1 ⁄2 pounds/ft2 (12.2 kg/m2), not including surface aggregate or insulation.

Modified bitumen roofing is similar to BUR, except that a polymer is mixed with the asphalt bitumen to produce a more flexible membrane that can achieve the necessary performance with fewer plies (typically two or three).

Modified bitumen roofing first caught on in Europe where, in some countries, it now holds as much as 90% of the market share. There are two basic types of modified bitumen roofing: those made with atactic polypropylene (APP) as the modifier; and those made with styrene-butadiene styrene (SBS) as the modifier. (Technically, APP is a

thermoplastic polymer, while SBS is a

thermoset plastic or elastomer.) Modified bitumens are typically sold in rolls that can be applied either in a traditional hot-mopped process, or with a torching process with welded edges and laps. Recently, polymer-modified bitumens have also become available as the mopping bitumen itself.

Compared with BUR, modified bitumen roofing is significantly more flexible. In fact, even with conventional BUR, modified bitumen is often used for the flashing details. These details may also increase the membrane life by taking the stress of building movement. Modified bitumen membranes are usually quite thick (120-180 mils or 3.0-4.6 mm), and with the tough cap sheet, they have nearly as much puncture and impact resistance as built-up roofs with aggregate surfaces—and more resistance than smooth-surfaced BUR. Some modified bitumens have significant recycled content (see sidebar).

Single-Ply Membranes

As the name implies, single-ply roofing is just a single, flexible, waterproof membrane. The simplicity of installation and the absence of smelly, smoking, hot-mopped asphalt have spawned an active search for effective, durable single-ply membranes. While there continues to be active research on these membranes, a collection of several materials now comprise roughly 35% of all commercial low-slope roofing in the U.S.

Among the first single-ply roofing membranes were neoprene rubber, vulcanized butyl, polyvinyl fluoride, and polyisobutylene (PIB). Sometimes these materials were fabricated onto asbestos-felt backing. Single-ply membranes were introduced primarily for very complex roofs with unusual geometries where hot-mopped BUR was difficult to apply. These have largely been replaced by ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), chlorosulfonated polyethylene (CSPE or Hypalon), and polyolefin.

EPDM is a type of synthetic rubber. It is a fully vulcanized or

thermoset elastomer. Carbon black is typically added for UV light resistance and strength, though a less-durable white EPDM is also available. Because it is fully vulcanized, seams cannot be welded with heat or solvents that partially dissolve the polymer; overlaps have to be sealed with adhesive. EPDM is highly elastic—it can be stretched more than 200% before reaching breaking strain, compared with just 2% for BUR. The material is somewhat susceptible to chemical attack from oils and fats, but has excellent ozone and UV resistance. EPDM does not contain chlorine or other halogens, which is an environmental advantage from a materials standpoint, but this results in lower fire resistance than halogenated single-ply membranes. For adequate fire resistance, a surface coating of ballast is generally required. As with other thermoset plastics, EPDM is not recyclable into new membrane.

PVC Membranes

PVC is a thermoplastic, making it fully weldable both during installation and for any necessary repairs—and welds can be as strong as the membrane itself. Flexibility is provided by adding plasticizers to the membrane. Popularity has grown significantly since PVC roofing was first introduced in the 1960s. Some early unreinforced PVC roofing membranes had premature failures, so most products sold today are reinforced with polyester or fiberglass. Loss of the membrane’s plasticizers can also result in premature failure. PVC is most commonly sold in white, but gray and a whole palette of brighter colors are also available from some manufacturers.

While PVC roof membranes have a lot going for them, they also have some problems. From an environmental standpoint, both the PVC itself is considered a problem (because of potential dioxin generation during manufacture, disposal, or accidental fires), and the plasticizers that are added to provide flexibility are potentially hazardous. The most common phthalate plasticizers, including DEHP or dioctyl phthalate, are suspected of being endocrine disrupters.

Some of the strongest opposition to PVC roofing comes from those concerned about fire. A letter obtained by

EBN that was sent to the Concord (Massachusetts) School Board by Richard Duffy, Director of the Department of Occupational Health and Safety of the International Association of Fire Fighters, expressed strongly worded concern about PVC roofing in the advent of a fire. “The International Association of Fire Fighters, which represents fire fighters throughout the United States and Canada, is concerned about the short- and long-term health hazards posed by exposure to combustion by-products of PVC fires.” Duffy referred to two hazards. First is the immediate risk of exposure to hydrogen chloride gas, a highly toxic gas that can cause skin burns and damage to the respiratory tract. “Exposure to a single PVC fire can cause permanent respiratory disease,” he said in the letter. The second hazard is the production of dioxin. While only small amounts of dioxin may be formed from burning PVC, according to Duffy, “it is one of the most toxic substances known to science.” Dioxin is a known human carcinogen and has been linked to reproductive disorders, immune suppression, endometriosis, and other diseases.

Despite these concerns, PVC roofing has made its way into some leading-edge “green” buildings, including the Herman Miller SQA Building in Holland, Michigan designed by William McDonough + Partners.

Russell Perry, AIA, of the firm explained that his company is “looking forward eagerly to a PVC-free future,” but in the meantime budget and performance requirements have sometimes meant using PVC. When they designed the Herman Miller building, he told

EBN, PVC “looked like the best alternative we had.” According to Perry, Bill McDonough designed the building so that a green (vegetated) roof could be retrofit onto it in the future (see photo below).

Chlorosulfonated polyethylene, or CSPE (known commonly by the tradename Hypalon, is a white polymer that is often marketed for its energy-saving reflectivity (see page 15). The chemistry of CSPE is somewhat unique, in that it is installed as a non-vulcanized or uncured elastomer; then cross-linking occurs upon exposure to heat and moisture, and the plastic converts into a fully vulcanized or cured thermoset elastomer. CSPE has excellent weather resistance, even in the typical high-reflectivity white. Fire resistance is provided by the chlorine in the elastomer formulation. While PVC has received the most attention from environmentalists, the chlorine in other plastics, such as CSPE, is just as big a concern, according to Charlie Cray, a toxics campaigner with Greenpeace.

Flexible Polyolefin Membranes

Due in part to environmental and health concerns about PVC, a number of manufacturers have begun producing non-chlorine-based, thermoplastic roofing membranes. Generically, this type of membrane is referred to as flexible polyolefin (FPO) or thermoplastic olefin (TPO). Polyolefin refers to a class of polymers comprised primarily of polyethylene and polypropylene. While PVC membranes obtain their flexibility with plasticizers, FPO or TPO membranes achieve their flexibility through the copolymers; there is no way for the plasticizer to leach out, as sometimes has occurred with PVC (resulting in brittleness over time). As with most PVC membranes, fiberglass or polyester reinforcement is used with these membranes.

Sarnafil, one of the leading PVC roofing manufacturers, with U.S. operations based in Canton, Massachusetts, introduced what they refer to as FPO roofing membrane in Europe around 1991 and in the U.S. in 1996. Sarnafil T membrane is a specially blended mix of copolymers and terpolymers of polyethylene. The product is recommended by the manufacturer only for ballasted roofing applications, however, according to vice-president Brian Whelan. Without chlorine or another halogen, the FPO membrane doesn’t pass the U.S. fire tests required by Factory Mutual and Underwriters Laboratory, so the stone or concrete paver ballast is required above it. Whelan told

EBN that most other producers of FPO add bromine to the chemical formulation to meet the fire performance requirements, but that Sarnafil will not do this because of environmental concerns about bromine. Bromine makes it more difficult to recycle polyolefin, and it may decrease the life of the product. Cray of Greenpeace told

EBN that bromine probably has similar—and perhaps even worse—environmental problems as PVC, though he did not know what quantities of the element are added for fire retardancy in polyolefin membranes. While Sarnafil T represents just a few percent of Sarnafil sales (the rest being PVC membrane), Whelan says that their FPO product should perform at least as well as PVC in a ballasted application. “If there’s a weakness to PVC,” said Whelan, “it’s in ballasted roofs.” He expects that in a ballasted or protected-membrane roof, FPO should last 20 to 30 years.

Another company, GenFlex Roofing Systems (previously General Tire), which has been producing EPDM roofing membranes since 1980 and PVC roofing membranes since 1984, introduced a TPO membrane in January 1997. Already, according to Glenn Orn of the company, TPO sales are expected to surpass PVC this year, and his company believes that TPO will eventually replace both PVC and EPDM. Unlike Sarnafil, GenFlex adds a fire retardant to their TPO formulation (believed to be bromine), so that it passes UL and Factory Mutual fire testing and can be used in exposed (unballasted) applications.

Concerns about PVC and the emergence of polyolefins have not gone unnoticed by industry giant Firestone, which manufactures a wide range of BUR, modified bitumens, and single-ply membranes. The company recently cancelled plans to build a multi-million-dollar PVC roof membrane plant, reportedly due to life-cycle concerns about PVC and how those might affect the market.

Hot-mopped built-up roofing and modified bitumen membranes provide their own attachment—the melted asphalt, coal tar, or modified asphalt serves as the adhesive. Not so with single-ply membranes. For single-ply membranes, the options are gluing the membrane to the insulation or roof deck, mechanically fastening the membrane, or leaving it unattached and holding it in place with rock or concrete-paver ballast. From an environmental standpoint, mechanical or ballasted attachment options are generally preferable to the use of adhesives—it does not result in VOC emissions from the adhesive, and the membrane can be removed and recycled more easily when it fails or when the roof needs to be modified.

Some mechanical fastening systems for single-ply membranes provide attachment without actually penetrating the membrane. The highly elastic membrane lies over special fittings, and caps are screwed on, sandwiching the membrane in the middle and holding it in place.

When ballast is used, it must be chosen to avoid damage to the material immediately underneath. The weight of ballast required depends on the local wind conditions. The use of

interlocking concrete pavers can reduce the total weight needed if the interlocking system helps prevent uplift.

The downside to a loose-laid or mechanically fastened membrane is that it is more difficult to identify the origin of roof leaks. Mark Rylander, AIA, of William McDonough + Partners, notes that a ceiling leak inside a building may be 30 feet (9 m) from the actual roof leak with single-ply membranes—particularly those that are loose-laid or mechanically fastened. This concern has brought some architects and specifiers back to BUR and modified bitumen roofs, after dealing with problems with single-ply products.

Environmentally Responsible Low-Slope Roofing

Standard low-slope roofing has little going for it from an environmental standpoint. Most materials have a limited life, after which they contribute significant waste to landfills—not only the roofing material itself, but also the insulation that is destroyed removing the roofing membrane. The most common roofing materials are black, absorbing solar energy and thus increasing the cooling loads in buildings. And some of the roofing materials introduced to solve the above problems—especially PVC formulations—have a whole set of environmental concerns related to the manufacture and disposal phases of their life cycle.

The ideal low-slope roofing material, relative to the environment, probably does not exist yet, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t do a lot better than conventional practice today. Below are some strategies for producing greener, more environmentally responsible roofs.

The protected-membrane roof (PMR)—also commonly referred to as the insulated roof membrane assembly (IRMA), a name given to it by Dow Chemical, which held a patent on the system until that patent expired in the 1970s—has a number of very significant environmental and performance features going for it.

Here’s how a protected-membrane roof works: The waterproof roof membrane is applied directly on the structural roof deck, rigid insulation (usually extruded polystyrene) is installed on top of this membrane, and the insulation is held in place with ballast (aggregate or concrete pavers). A drainage composite layer provides drainage between the roof membrane and insulation, and rainwater or snowmelt runs off through drains. Any type of membrane can be used with a PMR: conventional hot-mopped BUR, modified bitumen, or a synthetic single-ply membrane.

An important benefit is that the insulation protects the membrane from temperature extremes, freeze-thaw cycling, UV degradation from direct sunlight exposure, roof traffic, hail, and stress concentrations over insulation joints, all of which shorten the life of plastic and elastomeric materials in conventional systems (membrane above roof insulation).

Protected-membrane roofs have been around more than 30 years. Canada, the world leader in PMR technology, began actively promoting this approach in 1965, and it is well accepted today. In 1969, the University of Alaska adopted PMR as its primary roof specification, even at its Fairbanks campus where the 99% winter design temperature is -53°F (-47°C)! By carefully insulating the roof drains, the University’s roofs remain free of ice build-up even in this extreme climate.

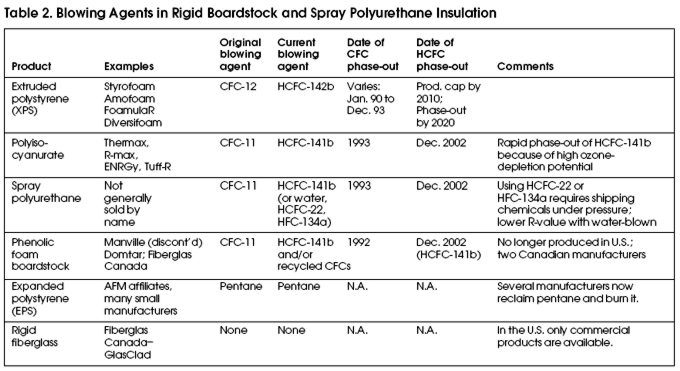

Dow Chemical originally developed the PMR system in the 1960s and markets Styrofoam Roofmate® specifically for this application. Extruded polystyrene (XPS) is the insulation material of choice for protected-membrane roofs, because of its very low moisture absorbency (the insulation in a protected-membrane roof can remain wet for long periods of time) and high compressive strength. Unfortunately, in North America all XPS is made with ozone-depleting HCFC-142b; in European countries that have phased out HCFCs, Dow Styrofoam is now made with CO2 as the blowing agent.

Foamglas, made by Pittsburgh Corning, can also be used with PMR systems. Foamglas is a 100% inorganic glass material that appears quite attractive from a materials standpoint, but it is fairly energy intensive to produce and quite expensive (about three times the cost of XPS). There is also some concern with Foamglas that it could be damaged by freeze-thaw action.

From an environmental standpoint, one of the outstanding features of the PMR system is the ability to reuse the insulation when a membrane failure necessitates reroofing. Re-use of insulation is easy because the insulation is rarely if ever today bonded to the membrane (either by adhesives or hot bitumen). The insulation is loose-laid on the membrane and held in place with ballast. If the insulation deteriorates while the membrane remains in good shape, it can be replaced with no disruption to the building, because the membrane is not affected.

One downside in some climates is the potential for plant and fungus growth at the membrane surface. Vegetation may grow up through the paver joints or stone ballast, and the roots in some cases may damage the membrane. The use of a drainage layer between the insulation and membrane has been found to reduce this problem.

Low-Slope Metal Roofing

Metal roofing is often specified as a highly durable and readily recyclable alternative for commercial roofing. The problem with metal roofing for commercial buildings has been that metal roofing was only practical for steeper slopes (generally greater than 3:12 pitch)—until recently, that is. Manufacturers of metal roofing now offer low-slope systems that work at pitches as low as

1 ⁄ 4” in one foot (0.25:12 or 2%), which is a typical pitch for low-slope commercial roofs. To remain watertight at such a low pitch, the standing seam for the roofing has to be specially designed to prevent water penetration. Roofing consultant Steve Hardy, of Moisture-Tech in Seattle, believes that metal roofing will ultimately prove one of the most environmentally friendly low-slope roofing alternatives.

Standing-seam metal roofing typically costs significantly more than conventional membrane roofing, but longer life and lower maintenance requirements often brings the life-cycle cost below that of membrane roofing. Even the first cost can be competitive, however, if the roofing eliminates the need for a structural roof deck. While most architectural panel roofing systems require solid backing, low-slope metal roofing is all structural, according to Steve Shull. The Span-Lok® roofing system from AEP-SPAN, for example, can be used at pitches as low as 0.25:12 and is capable of spanning up to 5 feet (1,500 mm). Shull suggests that it no longer makes sense to look only above the deck. “Look at the whole functional system,” he says. Shull argues that professionals in the roofing industry need to be proactive and knowledgeable in energy, rainwater management, and structural issues to maximize value to their clients.

Conventional low-slope roofing absorbs a lot of sunlight. The solar-heated roof surface contributes both to the cooling load of the building (by conducting heat through to the interior) and to the

urban heat island effect—a localized warming in urban areas that increases cooling loads in all buildings. If roofs can be made more reflective (higher albedo), those problems can be reduced, which will cut energy consumption.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, approximately $40 billion is spent annually to cool buildings—one sixth of all electricity generated in the U.S. In low-rise commercial buildings, heat gain through the roof may account for more than 50% of the total cooling load. With conventional low-slope roofs, it is not unusual for there to be a 70°F (39°C) difference in temperature between the roof surface and the ambient air temperature, which drives conductive heat gain into the building. The problem is exacerbated when the ceiling plenum serves as the conditioned air supply for the building, a very common strategy in commercial buildings. (Using such a plenum for conditioned air supply is also a significant cause of indoor air quality problems in buildings, particularly if volatized chemicals from the roofing make their way into the plenum.)

Highly reflective roofs can reduce cooling costs in commercial buildings by as much as 50%, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star Roof Products Program.

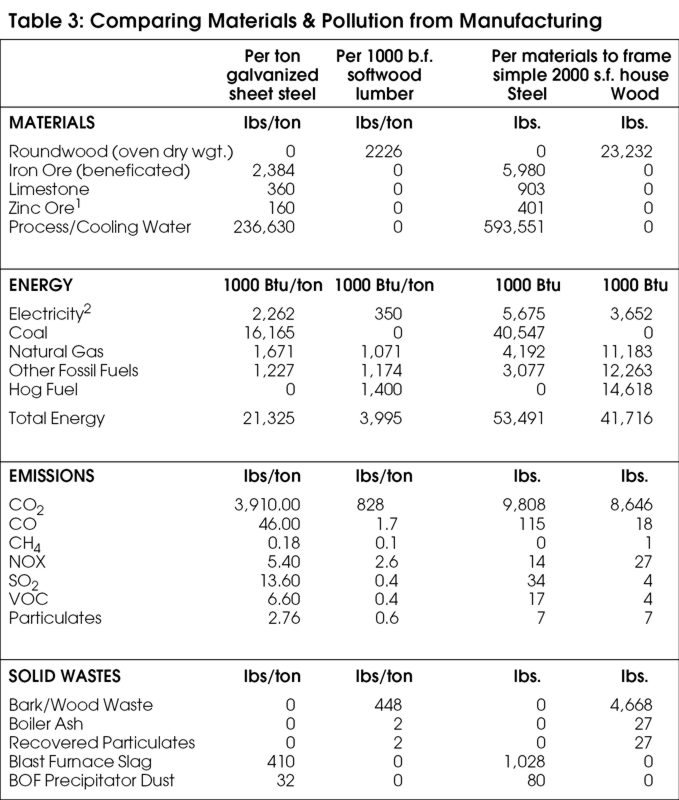

Data collected by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) showed dramatic reductions in roof surface temperatures and air conditioning costs after commercial buildings were retrofit with reflective roof coatings (see Table 2).

It is not only the reflectivity, or albedo, of a roof surface that determines how much it will heat up. The

emissivity of the surface also plays an important role.

Some materials with very high reflectivities, such as bright metal roofing, have very low emissivities (see Table 3). Low emissivity prevents the heated surface from re-radiating that energy, so the surface stays hot and heat conducts downward. In other words, it is possible for a dark roofing material to be cooler than another roofing material that is lighter in color and more reflective. To account for both of these parameters (reflectivity and emissivity), LBNL researchers have come up with the

solar reflectance index (SRI), as shown in Table 3. Paul Berdahl of LBNL told

EBN that SRI values are only approximate; wind conditions play an important role in determining the relative significance of the two parameters. When it’s windy, the emissivity of the roof is less significant.

Most low-slope roofing today is black or nearly black, with extremely low reflectivity and low SRI values. Some of the single-ply membranes, on the other hand, have excellent reflectance. EPDM, the most widely used single-ply roof membrane, is normally black. A white formulation of EPDM is available but not recommended because of durability problems. PVC is the most common reflective roof membrane today, though CSPE (Hypalon) and flexible polyolefins are also used.

For existing roofs, there are various spray-on or roll-on reflective coatings that can be used. Most common among these are acrylic coatings, which are essentially thick, specially formulated paints. Most offer the benefits of reflectivity as well as

some level of protection against weather. Most spray-on reflective coatings do not serve as the waterproof membrane, though some do.

Reflective roofing will gain a lot of attention when EPA’s Energy Star Roof Products program is formally unveiled at the National Roofing Contractors Association conference in Phoenix on February 7-10, 1999. The Memorandum of Understanding was finalized for this program in late October, and EPA is working to sign up manufacturer partners. To comply with the program (allowing an Energy Star label to be used in marketing the roofing products), the initial reflectivity of roofing products must be greater than or equal to 0.65, and it must be able to maintain reflectivity of 0.50 three years after installation under normal conditions. (Emissivity is not considered in the standards.) Rachel Schmeltz, program manager for the new EPA program, estimates that 10% to 15% of roofing products on the market would comply with the standards.

Green Roofs

Perhaps the most exciting development with low-slope roofing is the “green roof.” Green roofs, or living roofs, as the name implies, are planted with vegetation. In essence, these are protected-membrane roofs with soil and plantings (as well as insulation) installed above the membrane. While a fairly novel concept in commercial roofing in this country, green roofs actually have a long history. The first used birch bark as the membrane with sod on top of it. Because the membrane was not highly watertight, however, this primitive green roof design only worked if there was enough pitch. Beginning in the 1970s, green roofs have been used to a limited extent—primarily on underground or heavily bermed buildings. In parts of Europe, green roofs are widely used with both residential and commercial buildings.

To work on a commercial building, the green roof has to be very carefully designed and built. American Hydrotech and Soprema are the most active participants in green low-slope roofing in North America today, with Soprema having primarily a Canadian presence. Gensler Associates of San Francisco and William McDonough + Partners teamed up to design a green roof for the 190,000 square-foot (17,650 m

2) GAP office building in San Bruno, California, completed at the end of 1997.

The building has 70,000 square feet (6,500 m2) of green roof. The project used a two-ply SBS-modified bitumen roof membrane by American Hydrotech, the U.S. leader in green roofing. Hydrotech’s MM6125-EV modified bitumen was chosen because of its minimum 25% post-consumer recycled content (including recycled rubber and petroleum). Their standard modified bitumen (MM6125) has a minimum 10% recycled content. The roof section included 4” (100 mm) of Dow Styrofoam®, filter fabric, 3” to 4” (75 mm to 100 mm) of soil, and plantings of native grasses.

More recently, American Hydrotech has affiliated with ZinCo GmbH of Germany to offer a more comprehensive Garden Roof™ system.

Such a system was recently installed on the 75,000 square-foot (7,000 m2) Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center in Mashantucket, Connecticut. This system includes the same high-recycled-content modified bitumen membrane, plus several other key components provided by ZinCo to ensure long-lasting performance (see figure). Of these additional components, Floradrain is most interesting. It is a 2-1 ⁄ 4”-thick (57 mm) egg-crate-like material made from 100% recycled polyethylene. The depressions in the Floradrain retain water, while also permitting runoff of very heavy rainfall.

All these roofing components add considerable thickness to the roof—about 8” (200 mm), exclusive of the soil (but including insulation), and add considerably to the roof cost. Matthew Carr, the Garden Roof Product Manager for American Hydrotech says that with the thicker soil system (called an

intensive Garden Roof), the total installed roofing cost should be $15-$20/ft2 ($160-$215/m2). With a shallow-soil roof designed for grasses, sedums, and wildflowers only (as used in the GAP building), the total installed cost should be $10-$15/ft2 ($110-$160/m2). These costs do not include the additional structural requirements needed to carry the increased roof load.

Despite the high cost, Carr reports a great deal of interest in green roofs, particularly at a recent landscape architects convention in Portland, Oregon. The primary driver, he told

EBN, is stormwater detention. Such a roof can detain 50%–70% of the rainfall from a typical storm event, he said. Officials in Portland are very interested in figuring out a way to incentivize green roofs in the city as a way to reduce stormwater flows.

If Germany is any indicator of trends, green roofs could become very common. Many municipalities in Germany now mandate that with any new development, at least 50% of the site must be covered with vegetation at project completion. The easiest and least expensive way to comply with that is often to build green roofs. The German regulations are driven primarily by stormwater control and air purification provided by vegetation.

While the environmentally aware designer should certainly consider the various

system solutions for environmentally responsible roofing, there will be continuing developments in membrane materials as well. The polyolefin products described above will likely continue to evolve, and they may well replace PVC and EPDM. Polyolefin manufacturers may find ways of meeting UL and Factory Mutual fire performance standards without sacrificing recyclability or durability.

Meanwhile, there is exciting research being conducted on another class of polyolefins. Chemical engineer David Highfield, president of CHEMECOL in Charlotte, North Carolina and previously affiliated with McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry (after 25 years with Armstrong and Exxon), has been working on drop-in replacements for PVC since 1992. He has focused most of this work on a class of chemicals called metallocene polyolefins. Specialized catalysts allow metallocene polyolefins to be made with highly specific design properties. Applications are being investigated by his company for a wide range of building products, including flooring, wallcovering, and roofing. At a recent Boston symposium on PVC alternatives, Highfield claimed that metallocene polyolefin roofing would be able to satisfy all standard fire tests for both exposed and ballasted applications without any halogens (chlorine, bromine, etc.) or plasticizers.

Final Thoughts

Commercial roofing remains a challenge for architects, developers, and building owners who want to create more environmentally responsible buildings, but reasonable options are emerging. Look for continued evolution of polyolefin membranes, for example, as alternatives to PVC and EPDM. When possible, consider one of the leading-edge roofing strategies, such as green roofing, rainwater catchment, and power generation. Also, look for greater use of low-slope metal roofing systems. And remember to pay attention to the big picture. In the selection of roofing materials, Steve Shull stresses the importance of considering the whole roof system right from the start. “Rather than focusing on the detail of what deck, membrane, or insulation type is environmentally preferred, it should first be determined what design type offers the fewest environmental impacts.”

By making environmental performance a priority in roofing design and material selection, we can dramatically reduce the overall environmental impact of our commercial building stock. Roofing isn’t as glamorous a part of buildings as floor tile or interior finishes, but it is critically important in terms of the overall environmental impact.

– Alex Wilson

For more information:

National Roofing Contractors Association

O’Hare International Center

10255 W. Higgins Road, Suite 600

Rosemont, IL 60018

708/299-9070; 847/299-1183 (fax)

www.roofonline.org (Web site)

Rachel Schmeltz, Program Manager

Energy Star Roof Products Program

Office of Air and Radiation

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Washington, DC 20460

888/star-yes, 202/564-9124

schmeltz.rachel@epa.gov (e-mail)

www.energystar.gov (Web site)

American Hydrotech, Inc.

303 East Ohio Street

Chicago, IL 60611

800/877-6125

312/337-4998; 312/661-0731 (fax)

804/378-6125 (Matt Carr, Garden Roof product manager)

www.hydrotechusa.comBrian Whelan, Vice President

Sarnafil Roofing & Waterproofing Systems

100 Dan Road

Canton, MA 02021

781/828-5400; 781/828-5365 (fax)

www.sarnafilus.com (Web site)

webmaster@sarnafilus.com (e-mail)

Steve Shull

e-Roof, Inc.

835 Cedar Terrace

Deerfield, IL 60015

847/405-9808; 847/405-9864 (fax)

e-Roof@worldnet.att.net (e-mail)

(1998, October 1). Low-Slope Roofing: Prospects Looking Up. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/departments/feature