In little more than a decade, bamboo flooring has become a serious contender in the hardwood flooring market, and some believe that bamboo plywood is next. Lauded in environmental circles for its quick growth and the fact that it can be harvested without harming the plant, bamboo seems almost too good to be true. In fact, like any product, it has its downsides. “There is a lot of mythology about bamboo,” says Manuel Ruiz-Perez, professor of ecology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who has been researching bamboo for more than ten years. “You have to be cautious.”

In little more than a decade, bamboo flooring has become a serious contender in the hardwood flooring market, and some believe that bamboo plywood is next. Lauded in environmental circles for its quick growth and the fact that it can be harvested without harming the plant, bamboo seems almost too good to be true. In fact, like any product, it has its downsides. “There is a lot of mythology about bamboo,” says Manuel Ruiz-Perez, professor of ecology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who has been researching bamboo for more than ten years. “You have to be cautious.”

Now that bamboo flooring has grown beyond niche market status, it is beginning to attract more scrutiny. This article explores how bamboo measures up as a building material.

What is Bamboo?

Different species of bamboo, members of the grass family, are native to diverse climates around the world—from sub-Saharan Africa to northern Australia and from southeastern North America through much of South America. Bamboo also grows profusely throughout most of Asia.

Bamboo is especially notable for its strength, hardness, and rate of growth. Bamboo has greater compressive strength than concrete and about the same strength-to-weight ratio of steel in tension, according to Darrel DeBoer, an architect practicing in Alameda, California, and Karl Bareis, cofounder of the International Bamboo Association (now the World Bamboo Organization), in the 2000 book

Alternative Construction: Contemporary Natural Building Methods, edited by Lynne Elizabeth and Cassandra Adams. Bamboo grows much faster than trees, with some species growing up to 150 feet (46 m) in just six weeks, according to DeBoer and Bareis, and occasionally more than four feet (1,350 mm) per day.

Nearly all of the bamboo used in North America is grown in China, with small amounts coming from Vietnam and some poles for structural uses coming from South America. Most Asian cultures have a long history of using bamboo for food, building, and many other needs. Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) is known as mao zhu in China; moso is the Japanese name. It is the most widely cultivated species in China, with some plantations dating back hundreds of years. One fourth of the world’s population relies on bamboo for many of the objects used in daily life. Bamboo is used today for a wide variety of purposes unrelated to building; bamboo cutting boards are increasingly popular, and other bamboo products range from fabric to fencing, from paper to chopsticks.

Bamboo’s rapid regeneration and ability to be cut without killing the plant have earned it kudos within environmental circles, but some areas of concern have also emerged, especially as the industrial uses of bamboo multiply. “For probably 15 years in the 1980s to late ‘90s, people didn’t pay much attention to possible environmental effects,” says Ruiz-Perez. A 2005 report from Dovetail Partners, Inc., drawing heavily from research published by Ruiz-Perez and his collaborators, raised concerns about biodiversity, chemical use, and erosion, among other issues.

EBN contacted Ruiz-Perez to explore these concerns.

Land use and biodiversity

“Except when bamboo has replaced natural forest or very old plantations, bamboo comes with a positive environmental balance,” says Ruiz-Perez. He also notes that bamboo plantations have not replaced many natural forests in the last five years, compared to what was the case previously. Given its aggressive behavior, however, bamboo can invade nearby forests if it is not carefully managed. And farmers still replace pine, Chinese fir, and eucalyptus plantations, as well as rice fields, he reports, because bamboo is more profitable.

“Except when bamboo has replaced natural forest or very old plantations, bamboo comes with a positive environmental balance,” says Ruiz-Perez. He also notes that bamboo plantations have not replaced many natural forests in the last five years, compared to what was the case previously. Given its aggressive behavior, however, bamboo can invade nearby forests if it is not carefully managed. And farmers still replace pine, Chinese fir, and eucalyptus plantations, as well as rice fields, he reports, because bamboo is more profitable.

While replacing virgin forests with bamboo would be problematic from an environmental perspective, “China doesn’t have a lot of virgin forests,” says DeBoer. “Everything is so managed and agricultural in nature, I find it hard to get upset about anybody planting anything.” Doug Lewis, founder of bamboo flooring pioneer Bamboo Hardwoods, in Seattle, Washington, agrees: “I can’t imagine a better use for the land,” he says. Bamboo plantations do, however, have less biodiversity than forests. “There’s a tradeoff of what you lose on the biodiversity side and what you gain on the carbon sequestration and the water management side,” says Ruiz-Perez.

Given the short-term economic incentives, some bamboo plantations are managed in a way that hampers biodiversity and long-term productivity. “There is a tendency to overharvest,” says DeBoer, “to overuse what’s available because the factory demands such huge quantities of material.” Dan Smith, founder of Smith & Fong Company, in South San Francisco, California, however, points out a natural deterrent: “If you overharvest, the plant will send up a smaller pole next spring, and that crop is of no use to you. It’s an immediate slap in the face of the industry.” Clearcutting also has limited value, he says. “You’d get one-, two-, and three-year-old poles. You could mulch it up and make paper out of it, but in the spring, the bamboo will sprout again at maybe 1” [2.5 cm] diameter. The plant will eventually regenerate itself,” he says, “but in the meantime, you’ve got no material, no industry.”

Erosion can be a problem in newly planted areas, especially on steep slopes. Once established, however, bamboo is effective at reducing erosion. “Bamboo has been planted on edges of rivers where they have been controlling for flood and erosion,” says Ruiz-Perez.

One of the myths about bamboo flooring is that it is taking food away from endangered Giant Pandas. While they do rely almost exclusively on bamboo shoots and leaves for food, pandas no longer occupy the lowlands where bamboo is now harvested for industrial uses. So, the remaining pandas eat only species that grow at the higher elevations that represent the remnants of their habitat.

Moso bamboo is grown both for food and for fiber, and plantations growing edible bamboo shoots are more likely to use pesticides and fertilizers than those producing fiber. Farmers who can afford it may treat their plantations to reduce weeds and destructive insects, according to Ruiz-Perez. Overall, one-quarter to one-third of moso plantations use small amounts of pesticides, he says, but the percentage among those growing bamboo for industrial uses is much lower. Fu Jinhe, Ph.D., program officer at the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR), confirms this perspective. “I’ve hardly heard of pesticides for moso bamboo plantations,” he reports, noting that they are occasionally used in shoot production.

Fertilizers are far more common, although, as with pesticides, they are of greater concern in shoot production than in fiber production. The traditional practice of spreading food scraps, manure, and human waste on bamboo groves is still common, especially in poor provinces. When farmers use industrial (and more environmentally harmful) fertilizers, they tend to emphasize the nitrogen component, says Ruiz-Perez. Fortunately, the wealthier Chinese provinces, in which farmers can afford to use industrial fertilizers, are also the most progressive relative to environmentally responsible management. In some regions, local governments pay farmers to harvest only mature bamboo, encourage biodiversity, and avoid chemical inputs, says Ruiz-Perez.

Carbon sequestration

Bamboo plantations are lauded for their ability to sequester carbon. As plants grow and photosynthesize, they take in carbon dioxide (CO2) and emit oxygen (O2). They convert the carbon into the carbohydrates that make up their structure. By sequestering carbon, plants reduce the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, which is the main contributor to climate change.

There are competing claims as to whether bamboo sequesters more carbon than wood—the answer depends on how you look at the process. While a healthy natural forest stores more carbon than a bamboo plantation at any given time, the bamboo plantation, because of the speed at which bamboo grows, removes more carbon from the atmosphere in any given period. Carbon is sequestered not only in living plants but also in any products made from those plants until the carbon is released back into the atmosphere through decomposition or burning. So the question of whether trees or bamboo sequester more carbon depends on what happens to the fibers after they’re harvested and how long they remain intact. If the bamboo is used to make long-lasting products, it will sequester more carbon over time than almost any other land use, according to Ruiz-Perez.

Although bamboo forests could be certified according to the standards of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), none have been yet. “I think it’s a matter of FSC’s interest in establishing a criteria and finding people willing to allow them in and pay for their services and certification,” says Smith. Some forests in Asia and South America where bamboo is grown alongside wood have been FSC certified, but, until recently, FSC was reluctant to address bamboo forests or plantations, since bamboo is not a wood. An FSC “Guidance Note” from May 2004, however, opens the door to the development of standards for bamboo plantations specifically, and such standards have been developed in Colombia. Jeff Hayward, Asia Pacific regional manager for the Rainforest Alliance’s SmartWood program, notes that “while there is great potential for bamboo if standards could be arrived at that would settle these questions, the FSC has not produced such a process or standards in China.”

Ruiz-Perez says he is unaware of any system that certifies the environmental management of bamboo plantations, though he notes that some entire counties in China have earned “green labels” from the government. These certifications are not internationally recognized, but “inside China they have high prestige,” he reports, noting that only a small fraction of counties are certified, and a handful of these produce bamboo.

Uses of Bamboo in Building

While North America’s use of bamboo as a building material is largely limited to flooring and the occasional plywood panel, much of the developing world uses bamboo scaffolding in construction. Designers are constantly experimenting with new uses for the material, however, and rediscovering old uses. DeBoer likes using woven bamboo panels as a finished wall surface in place of drywall, for example.

While North America’s use of bamboo as a building material is largely limited to flooring and the occasional plywood panel, much of the developing world uses bamboo scaffolding in construction. Designers are constantly experimenting with new uses for the material, however, and rediscovering old uses. DeBoer likes using woven bamboo panels as a finished wall surface in place of drywall, for example.

Bamboo’s strength, flexibility, and ready availability have made it a dominant structural material throughout much of the world for centuries. Its use in modern, mainstream construction, however, is rare—especially in North America. A few pioneering engineers in South America have demonstrated bamboo’s potential, but they remain the exception.

Many, including INBAR, viewed the lack of internationally recognized standards as a serious impediment to the expanded use of structural bamboo. “The lack of codes and standards has kept architects and designers away from bamboo, even from expressing their requirements for bamboo as a building material,” according to a 1997 INBAR newsletter. This was remedied in 2000, when the International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO) passed the “Acceptance Criteria for Structural Bamboo” (AC162). The publication of this document is a big deal for people wanting to use bamboo structurally, according to DeBoer. “AC162 includes formulas for engineers to use and testing criteria for whatever species you’d want to use,” he reports.

Despite this progress, using bamboo as a structural material in North America remains difficult. “It’s a challenge to fit it into the way that we build,” DeBoer says. “One of our big challenges is the fact that you need so much insulation in most structures in this country,” he told

EBN. “You need to be able to nail through the top and bottom of your roof structure, and once you need 12” [30 cm] of insulation or airspace, some piece of wood always wins.” Building with bamboo also requires a lot of attention to detail, which makes it attractive where labor is cheap but less appealing in the U.S. and Canada.

Given the difficulties of creating an insulated wall or roof system using structural bamboo, it isn’t surprising that the most comprehensive effort in North America to build with structural bamboo is taking place in Hawaii, where insulation isn’t critical. Bamboo Technologies, Inc., a sister company of Bamboo Hardwoods, has used the ICBO rules to gain code acceptance for its use of bamboo to build homes and other buildings. In November 2004, ICC Evaluation Service, Inc., issued its report ESR-1636 recognizing that Bamboo Technologies’ bamboo complies with the relevant codes: “The structural bamboo poles are used as structural elements in wall, roof, and floor trusses (panels) or as individual compression and/or tension members in Type V non-fire-resistance rated residential and commercial construction.”

Bamboo Technologies cuts and prepares the poles for its structures in Vietnam, using the species tre gai (Bambusa stenostachya). To protect against insects and decay, the poles are treated with boric acid and coated with a finish that emits no volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Bamboo Technologies is currently sponsoring a competition to develop additional designs for its projects—registrations are due by the end of 2006.

Flooring

The most common use of bamboo in North American construction has, by far, been as a flooring material. When we first wrote about bamboo flooring, in 1997 (see

The most common use of bamboo in North American construction has, by far, been as a flooring material. When we first wrote about bamboo flooring, in 1997 (see

EBN

Vol. 6, No. 10), we found only eight companies supplying the North American market. In contrast, about 200 companies imported about 45 million ft2 (4.2 million m2) bamboo flooring into the U.S. in 2005, estimates David Knight, president and CEO of Teragren, LLC (formerly Timbergrass), in Bainbridge Island, Washington. That represents about 2% to 3% of the market for wood floors, according to Knight.

One of the largest North American bamboo distributors, Teragren has achieved its distribution scale by selling through retail flooring outlets—it has product in 1,700 stores in the U.S. and Canada and hopes to be in 3,000 by the end of 2006, he says. Like many of the other reputable importers, Teragren has an exclusive relationship with a producer in China—that producer now has three factories and over 500 employees, and Teragren handles two-thirds of its production (the rest goes to France and various outlets in Asia).

Varieties. Bamboo flooring comes in several varieties (see table). First, it can be solid or engineered. Solid bamboo is not solid planks of bamboo, as the name implies, but rather strips made up of distinct layers of bamboo. Engineered flooring is made of a bamboo top layer glued to one of a variety of materials. The surface bamboo can be oriented either vertically or horizontally. Horizontal-grain, or flat-grain, flooring is the more traditional look and features bamboo’s characteristic nodes, or “knuckles.” Vertical-grain, or edge-grain, flooring, on the other hand, has the bamboo strips lined up on edge, resulting in a more uniform look and reducing the knuckle appearance.

Bamboo flooring is commonly sold in two color tones: a light blond (bamboo’s natural color) and a darker hue, often described as “carbonized.” The darker color comes from heat-treating the bamboo, which actually

caramelizes the sugars in the fiber. Bamboo flooring can also be stained. Bamboo Hardwoods, for example, offers “cherry” and “fruitwood” colors for its premium floors.

Within the last few years, several bamboo flooring companies have introduced strand products, made by separating the bamboo into individual fibers and then binding them under heat and pressure with a phenol-formaldehyde resin. Smith & Fong calls its version Plyboo® Strand™ flooring, and Sustainable Flooring, LLC, calls it Strandwoven bamboo. Teragren had planned to unveil its own Synergy strand product in mid-2005 but quality concerns delayed the launch to February 2006.

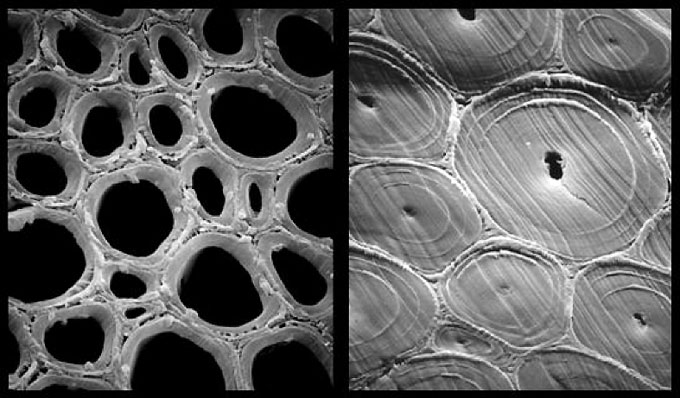

Hardness. One factor that differentiates high-quality bamboo flooring and plywood from lower-quality products is the age at which the culms were harvested. Moso bamboo culms emerge from the ground at their full dimension of up to 8” (200 mm). They spend the next several years “hardening their arteries,” whereby the capillaries thicken toward the inside but the diameter never changes. What begins as almost entirely sugar and water lignifies into hard cellulose.

Hardness. One factor that differentiates high-quality bamboo flooring and plywood from lower-quality products is the age at which the culms were harvested. Moso bamboo culms emerge from the ground at their full dimension of up to 8” (200 mm). They spend the next several years “hardening their arteries,” whereby the capillaries thicken toward the inside but the diameter never changes. What begins as almost entirely sugar and water lignifies into hard cellulose.

While three-year-old culms can be made into flooring, some companies claim to harvest only after five years. According to Knight, “We can see that younger than five or six years, the fibers aren’t as long. The longer the fiber, the better the stability.” Smith agrees, noting, “I interpret the six-year point as the maximum apex for strength and for keeping the resource healthy.” Others, including Lewis, believe bamboo reaches its peak hardness at about three years, and doubt whether there is any benefit to letting it age further.

Lewis also questions whether it’s possible to ensure that only older culms are used. “I couldn’t tell if a pole is much beyond three years,” he told

EBN. Smith admits that ensuring the use of older culms is difficult. “I don’t think there’s any way to control, to say ‘I want six-year growth’,” he says. Trevor Gilmore of Bamboo Mountain, Inc., in San Leandro, California, agrees, noting, “The purchasers have to have a really good relationship with the manufacturers they work with.”

While it’s hard to tell a pole’s age by looking at it, most bamboo farmers actually track their plants carefully. Culms are often marked with a name and date after their first year, when they’ve reached full size. Some companies even use electronic tagging systems. “We go to the farmer and purchase it from him after the first year. We put our name and ID chips into it and know it’s ours,” says David Kurland, of Mill Valley Bamboo Associates in Larkspur, California.

While it’s hard to tell a pole’s age by looking at it, most bamboo farmers actually track their plants carefully. Culms are often marked with a name and date after their first year, when they’ve reached full size. Some companies even use electronic tagging systems. “We go to the farmer and purchase it from him after the first year. We put our name and ID chips into it and know it’s ours,” says David Kurland, of Mill Valley Bamboo Associates in Larkspur, California.

While bamboo flooring products are lauded for their hardness, the actual hardness of the available products varies substantially. The age at which the culms are harvested plays a role—flooring from less-reputable distributors may be made from culms younger than three years old, so the resulting product dents easily. The bamboo variety is also important. “We could actually dent it with our fingernail,” Knight says of a competitor’s product that he believes is made of a subspecies of moso bamboo.

Various manufacturing processes also affect the hardness of the finished product. Notably, heating bamboo to caramelize it softens the fibers. Teragren’s vertical-grain caramelized flooring is rated at 1,470 newtons on the Janka hardness test, compared with 1,850 for the same product in the natural color. (Red oak scores about 1,360 on the same test.) The difference is less dramatic in the flat-grain configurations, but caramelizing still reduces the hardness by about 10%. Strand bamboo, on the other hand, is much harder than conventional bamboo flooring and generally considered appropriate for commercial and other high-traffic areas. Smith & Fong and Teragren both claim their strand flooring is twice as hard as red oak, and Sustainable Flooring describes it as “bomb-proof.”

Plybamboo

Over the past few years, bamboo flooring companies have begun experimenting with other interior finish materials made from bamboo. The most common of these is a product designed to replace plywood. Smith & Fong’s latest product offering is Neopolitan™ plywood, which contrasts natural bamboo with darker caramelized bamboo.

Manufacturers of bamboo flooring and plywood handle potentially toxic chemicals, including binders and finishes; produce a lot of solid waste; and run equipment that emits combustion gases. The manufacturers’ responsibility in dealing with these potential environmental and health hazards is unclear. “A lot of these companies are dumping finish down the drain at the end of the day,” says Ryan Wuest of iFloor.com. Wuest notes that iFloor didn’t always look into its manufacturers as carefully as it does now. “Once we found out what [our previous suppliers] were doing, we didn’t want anything to do with them,” he says. Most major North American distributors of bamboo flooring and plywood claim to work with only reputable manufacturers and tout their long-term relationships with those producers in vouching for their commitment to quality and environmental responsibility.

Manufacturers of bamboo flooring and plywood handle potentially toxic chemicals, including binders and finishes; produce a lot of solid waste; and run equipment that emits combustion gases. The manufacturers’ responsibility in dealing with these potential environmental and health hazards is unclear. “A lot of these companies are dumping finish down the drain at the end of the day,” says Ryan Wuest of iFloor.com. Wuest notes that iFloor didn’t always look into its manufacturers as carefully as it does now. “Once we found out what [our previous suppliers] were doing, we didn’t want anything to do with them,” he says. Most major North American distributors of bamboo flooring and plywood claim to work with only reputable manufacturers and tout their long-term relationships with those producers in vouching for their commitment to quality and environmental responsibility.

Several bamboo flooring companies in the U.S., including Teragren and Mill Valley Bamboo, go a step further, noting that the manufacturers they work with are registered under the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards 9001 for quality control and 14001 for environmental management systems (EMS). In principle, ISO 14001 registration means that an accredited, independent auditor has reviewed the company’s EMS for compliance with the ISO standard and conducted site visits to confirm that the EMS is being implemented appropriately. In practice, however, the significance of these ISO registrations in China is not so clear. ISO-accredited auditors from Europe and North America are not welcome in China, apparently because they are too demanding, according to Jason Morrison, director of the Pacific Institute’s Economic Globalization and the Environment Program. “I’ve heard first-hand from a registrar that they have been blacklisted from doing certifications in China,” Morrison reports. Instead, the Chinese government is accrediting its own registrars to ensure that Chinese companies can get registered. “They see it as a market-access issue,” says Morrison, noting that being registered for ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 is considered a prerequisite for supplying some North American and European companies.

The fossil fuels required to move bamboo products halfway around the world constitute an environmental strike against the product, although oceangoing freighters move material more efficiently than trucks. No North American companies are currently growing bamboo for building uses, and, due primarily to the high cost of labor in North America relative to the parts of the world where bamboo is currently grown for building uses, this situation is unlikely to change.

Preservative treatments

“The use of bamboo structurally runs the gamut from not treating at all up to some treatment systems that can be fairly toxic,” DeBoer told EBN. DeBoer notes that fairly benign treatments, based on smoke and boric acid, are generally used, but that more toxic treatments, based on arsenic and copper compounds, are also used on a fairly limited basis. “The cost of bamboo poles triples when you add preservatives to them. So when bamboo is used locally, it is almost never preserved. Only the poles they export to Europe and North America have any preservative on them,” he says. Bamboo products used as interior finishes, including flooring, are rarely treated with preservatives. “In general, bamboo flooring doesn’t need a lot of preserving because it’s protected on the interior of buildings,” says DeBoer.

As those in the bamboo business will be first to point out, bamboo products qualify for the Materials and Resources credit for rapidly renewable materials in the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED® Rating System. A few products, made without the use of urea-formaldehyde binders, also meet the criteria for the Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) credit for low-emitting composite materials. “All of our flooring is made with 100% formaldehyde-free glues,” says Bamboo Mountain’s Gilmore. “Most people who are interested in bamboo flooring are very interested in the formaldehyde in it. We used to have just one line of flooring that was formaldehyde-free. But 70% of our clients went with that line, so we decided to do that across the board.” Bamboo Mountain’s flooring is made to its specifications by a manufacturer just north of Hong Kong, who uses an isocyanate resin binder, similar to those used in ag-fiber panel products. Gilmore couldn’t say what measures were taken to protect the factory workers from this highly reactive binder.

In addition to Bamboo Mountain’s solid flooring, all of the strand flooring products, made with phenol-formaldehyde binders, clearly meet the requirements of the IEQ credit. Whether bamboo products made with conventional, urea-formaldehyde binders should disqualify a project from achieving the credit is less clear. Knight, whose products do contain added urea-formaldehyde, says USGBC has sent him two written opinions drawing opposite conclusions in just the last two months. Some projects are known to have achieved the credit even using bamboo flooring made with a urea-formaldehyde binder, but more recent opinions suggest that this may no longer be allowed.

Product emissions are low in part because “bamboo has very little naturally occurring formaldehyde, especially compared to hardwood,” Knight explains. Additionally, many manufacturers use specially formulated urea-formaldehyde binders from European chemical companies that are formulated to meet emission limits widely used in Europe.

To date no bamboo products have been certified through the Greenguard Environmental Institute’s program (see

EBN

Vol. 12, No. 10) or the Resilient Floor Covering Institute’s FloorScore™ program (see

EBN

Vol. 14, No. 10). Most companies claim that their products are in compliance with Europe’s E1 standard, however, which limits formaldehyde concentrations under test conditions to 0.1 parts per million (ppm), and a few claim to meet a stricter E0 standard, although the requirements for this standard are not well documented. Teragren pegs its product’s average formaldehyde levels at 0.0155 ppm under ASTM’s E-1333 test for the E1 standard, and Steve Simonson of iFloor says his company can offer E0-compliant glue for large custom orders.

The ASTM E-1333 test for the E1 standard differs from the procedures used by Greenguard and FloorScore, so allowable concentrations are not directly comparable, according to Scott Steady of Air Quality Sciences, Inc., the lab that does testing for Greenguard. They can be used as a rough guide, however, so the fact that Greenguard’s threshold is 0.05 ppm, or half the maximum E1 level, is significant. “We’ve done testing on some bamboo floors that look great, others that don’t,” reports Steady. FloorScore’s standard, based on guidelines from the State of California, is even tighter than Greenguard’s. “If they want to meet the Greenguard or California guidelines, additional encapsulation and responsible choice of adhesives and coatings may be necessary,” advises Steady.

Final Thoughts

Bamboo certainly has the potential to maintain its status as a green product of choice, but as it becomes more common, suppliers will have to do more to earn that status. The tremendous growth in the market for bamboo flooring and other products is magnifying the potential negative effects and drawing less reputable players into the game.

Whether through FSC or some other program, industry leaders need to create a system that backs up their claims about resource management and manufacturing practices with the credibility of an independently verified, third-party certification program. And, given their dependence on questionable urea-formaldehyde binders, they need to start participating in North America’s existing testing and certification programs for chemical emissions from their products. Certification programs do add to the cost of doing business, but they are the best way to prove the environmental merits of bamboo products.

– Nadav Malin and Jessica Boehland

For more information:

Darrel DeBoer, architect

Alameda, California

510-865-3669

www.deboerarchitects.com

Dovetail Partners, Inc.

White Bear Lake, Minnesota

651-762-4007

www.dovetailinc.org

International Network for Bamboo and Rattan

Beijing, China

www.inbar.int

World Bamboo Organization

www.world-bamboo.org

Selected Manufacturers:

Bamboo Hardwoods

www.bamboohardwoods.com

Bamboo Mountain

www.bamboomountain.com

iFloor

www.ifloor.com

Mill Valley Bamboo Associates

www.mvbamboo.com

Smith & Fong Company

www.plyboo.com

Sustainable Flooring, LLC

www.sustainableflooring.com

Teragren, LLC

www.teragren.com