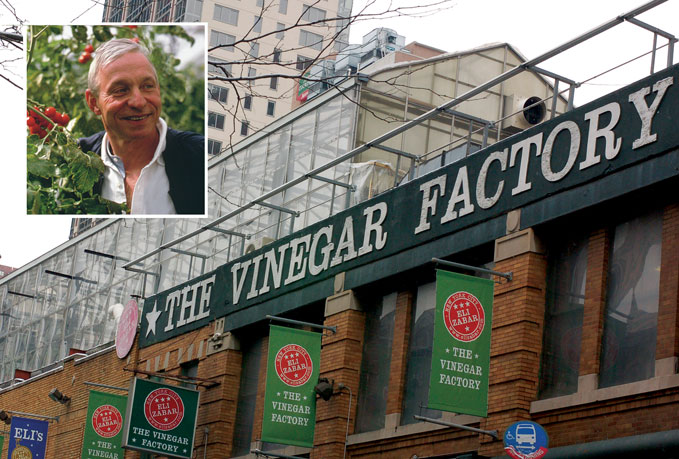

Eli Zabar’s bakery and market on East 91st Street in Manhattan seems like a classic New York market. On my half-dozen visits over as many years, I’ve reveled in the gorgeously displayed vegetables and fruits, the vast array of cheeses, and the wide assortment of breads and pastries baked next door. But Zabar’s market, the Vinegar Factory (named in reference to a prior use of the property), is anything but typical. The sprawling facility connecting multiple buildings demonstrates an unconventional dimension of agriculture: farming that is intertwined with the urban landscape.

In 1995, Eli Zabar, renegade scion of the famous West Side Zabar family, whose markets have been serving New Yorkers for 75 years, began building greenhouses atop his two- and three-story brick buildings on the Upper East Side. These greenhouses, covering nearly a half-acre in area, are producing greens, tomatoes, berries, andeven figs that are sold—not cheaply!—in his market downstairs.

Zabar is ahead of the curve, a pioneer in a trend that is likely to grow dramatically in the coming years. I’ve long been fascinated by the potential for integrating agriculture into the urban landscape—the sea of flat roofs and empty lots in our larger cities. This article looks at the motivation to turn to urban and suburban areas for food production, then examines how to do this, including some of the ways food wastes are being turned into nutrients to grow vegetables, eggs, meat, and fish in our towns and cities.

The Case for Building-Integrated Food

The spike in energy prices in 2008 forced a lot of people to rethink the 1,500-mile journey that, according to author Bill McKibben, an average bite of food travels in the U.S. from where it is grown to where it is eaten. Shipping a head of lettuce from California’s Salinas Valley to New York takes 36 times as many calories as that lettuce contains. According to Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute, we consume two-thirds as much energy to transport food as we use to grow it.

Beyond energy cost, there are additional vulnerabilities in our conventional food-production system. Prolonged drought in California, the start of a new La Niña climate pattern that may exacerbate drought, and inadequate long-term flows in the Colorado River all point to a future with possible water shortages in California’s primary vegetable-producing regions. These vulnerabilities are reviving interest in growing food locally.

Beyond energy cost, there are additional vulnerabilities in our conventional food-production system. Prolonged drought in California, the start of a new La Niña climate pattern that may exacerbate drought, and inadequate long-term flows in the Colorado River all point to a future with possible water shortages in California’s primary vegetable-producing regions. These vulnerabilities are reviving interest in growing food locally.

The closer to home that vegetables are grown, the healthier they are likely to be. Vitamins in fresh produce break down over time, and some vitamins may never fully form in fruits like tomatoes that are often picked green and artificially ripened in transit. The same goes with taste; vine-ripened tomatoes are far tastier than their machine-harvested brethren from hundreds or thousands of miles away. There may also be health benefits to smaller-scale production. In huge agribusiness operations,

Salmonella outbreaks and other contamination problems become national problems affecting thousands of people. According to McKibben, four companies slaughter 81% of the nation’s beef, and a single Ohio farm produces three billion eggs per year. At a smaller scale, any problems that do come up are much more contained, with smaller impacts on the food supply.

Finally, growing food closer to home can help to build awareness of—and appreciation for—food production. Many children growing up today have no relationship with farming; they have never seen a head of lettuce being grown, picked a tomato from the vine, or watched chickens scratching in the soil. Such awareness will help to build respect for the Earth and environment on which we all depend.

Farming and Gardening Vacant Land in Our Cities

Most American cities have a lot of vacant land. A 2000 study by the Brookings Institution,

Vacant Land in Cities: An Urban Resource, reported that 70 major American cities averaged 15% vacant land area. Geographically, cities in the South had the most vacant land (19.3% average) and the Northeast the least (9.6%). A movement has been growing slowly for several decades to use that land productively.

This land can be used both for nonprofit and for-profit agricultural operations and community gardens. Provided here are a few examples out of the hundreds that can be found around North America.

Commercial farming operations

Back in 1968 in Chicago, Ken Dunn recognized the potential that vacant land offered for localizing food production and achieving social goals, and he launched City Farm. The farm is one project of the Resource Center, a nonprofit organization Dunn founded that runs a host of programs devoted to building community and strengthening local economies (www.resourcecenterchicago.org). Dunn grew up on an Amish-Mennonite farm in Kansas and has worked to bring to Chicago the Amish philosophy of nourishing and protecting soil, plants, animals, and community. City Farm began “mostly as a social justice project,” Dunn told

EBN. Over four decades the organization has farmed a varying area of unused land—currently about two acres (0.8 ha)—using a unique model of farming that protects food from being contaminated by the soils below.

“Almost everything in urban areas is contaminated to some level,” Dunn said. He convinces owners of sizeable urban sites (typically one acre or larger) to “loan” the land to City Farm for several years. A site is graded and compacted, then an impermeable four-inch (100 mm) layer of local clay (typically sourced from construction sites as a waste product) is laid down on top of the existing soil. City Farm then puts down safe, uncontaminated compost on top of the clay, creating growing beds that are 24 inches (600 mm) deep. The farm is established in this compost, 1,000 tons of it per acre (2,200 tonnes/ha).

City Farm has ensured that the compost is safe—free of herbicides often used on lawns, for example—by controlling exactly what gets composted. City Farm collects food waste, including meat and dairy, from 18 restaurants in the city. Until recently, the organization composted this organic matter itself, using a massive 15-yard (12 m3) hopper and grinder. This composting operation was spread over an acre of land City Farm owned with rows of compost 15 feet (5 m) deep. In 2008, due to red tape from the City of Chicago, City Farm had to close down its own composting operation, and it now trucks the food waste it collects 80 miles (130 km) to a commercial composting facility in Indiana. The organization hopes soon to be able to produce its own compost again—and regain full control over the quality.

To support its operation—and pay a living wage to its three full-time employees—City Farm sells heirloom tomatoes, salad greens, and other produce to 20 restaurants for top dollar ($3.50/pound for tomatoes and $20/pound for greens). At the same time, farm stands sell produce at more affordable prices to local residents.

While City Farm is currently farming only two acres (0.8 ha), significant expansion is likely in the next year with several contract gardens for specific restaurants and a hospital. The hospital, which had to delay construction of a new building due to tight credit markets, is negotiating with City Farm to custom-farm the one-acre (0.4 ha) site and provide all of the produce to the hospital (which will be able to serve more nutritious food to its patients). Even with this likely expansion, though, Dunn is frustrated that their penetration remains so low in a city with 20,000 acres (8,000 ha) of vacant land. “We could farm 100 more acres every year if people took us seriously,” he said.

SPIN Farming

Dan Bravin and Martin Barrett own City Garden Farms in Portland, Oregon. It is one of dozens of businesses throughout North America that are implementing the “SPIN Farming” model of farming enterprise (SPIN for Small Plot INtensive). In 2008, they farmed a dozen small plots, ranging in size from 500 ft2 (46 m2) to 3,000 ft2 (280 m2) around the city, with total planted area of about a quarter-acre (0.10 ha). The land is in backyards of Portland residents who offer it freely.

City Garden Farms sells its produce through a CSA (community-supported agriculture) program. (In a CSA, members pay a seasonal fee in exchange for a weekly delivery of produce.) The farm recouped its startup costs in 2008—about $11,000 spent primarily on a rototiller, seeder, co-linear hoe, and wheel hoe. “It’s not a year-round, full-time employment income,” Bravin told

EBN, but with some growth in the farm area and in CSA members from the current 50, the farm should soon provide a living.

The SPIN Farming business model was developed by Wally Satzewich and Gail Vandersteen from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. In the 1980s, they were farming 20 acres (8 ha) of irrigated farmland 40 miles (60 km) north of Saskatoon, but they lived in the city and kept a couple of small plots there for salad crops. They found that they could grow three crops a year on the intensively managed plots in the city and deliver fresher food to their markets. After six years, they sold their larger property and moved their farming totally into the city.

In the years since, they’ve perfected an intensive, standardized, small-plot farming technique based on standard rows governed by the width of their rototiller. Most such operations are managed organically with extensive use of compost. The approach can be used in both urban and suburban areas, the primary limitation being the availability of sites with full access to sunlight.

Satzewich continues to operate a sub-acre farm that is spread over 25 residential backyard plots in Saskatoon, but he and Vendersteen also produce educational guidebooks about SPIN Farming. They have teamed up with Roxanne Christensen, the co-founder and president of the Institute for Innovations in Local Farming in Philadelphia, to promote SPIN Farming in the U.S. Christensen told

EBN that 2,200 people have purchased the SPIN Farming guides and, based on the members of an active SPIN farmers email support group, she estimates that there are about 300 SPIN farmers, mostly in the U.S. and Canada, though also in the U.K., Ireland, Australia, and the Netherlands.

At City Garden Farms, Bravin has standardized beds that are 2' x 25' (0.6 x 7.6 m), and he estimates that each can earn about $100—or $300 per year if three crops are grown on it. His approach is to harvest an entire bed, then prep and reseed that bed. He describes the SPIN Farming approach as very similar to what has been done in Havana, Cuba, since the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in the island nation losing access to cheap fossil fuels.

Community gardens

Along with various models of commercial-scale farming in urban areas, community gardens have also been growing in popularity. There are thousands of grassroots community garden initiatives throughout North America. Some involve just a few individuals sharing growing space on land owned by a city. Others are more extensive, with multiple garden plots on land owned by a nonprofit community gardening organization; some are on private land.

Nuestras Raices in Holyoke, Massachusetts, is a network of community gardens and farm enterprises in this economically depressed western Massachusetts city of 44,000, 40% of whom are Puerto Rican and with unemployment rates as high as 31% in parts of the city. Nuestras Raices (Spanish for “our roots”) was founded in 1992 as an outgrowth of the La Finquita community gardens in the city (www.nuestras-raices.org). La Finquita today includes 31 family garden plots, including one for the Broderick House, a homeless shelter, while the umbrella organization, Nuestras Raices, has blossomed into a diversified economic- and community-development organization that includes eight different community garden networks, two youth gardens, a women’s leadership group, an environmental justice initiative focused on toxic pollution in the city, a green jobs program, and the four-acre (1.6 ha) Tierra de Oportunidades Farm along the Connecticut River, which was purchased with support from the Trust for Public Land.

In Detroit, another area suffering from extremely high unemployment rates, the nonprofit group Urban Farming has emerged as an important resource in the struggle to address poverty and hunger. The organization, launched in 2005, manages or oversees more than 50 community gardens in Detroit, and it has expanded nationwide with hundreds of gardens in New York, Newark, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and other cities—more than 400 sites total (www.urbanfarming.org). Urban Farming partners locally with corporations as well as youth groups, senior centers, churches, schools, and other community-based organizations with the mission to “eradicate hunger while increasing diversity, motivating youth and seniors, and optimizing the production of unused land for food and alternative energy.” Harvested food is mostly distributed through local food banks, though neighbors are welcome to pick food for free, according to founder Taja Seville.

Permaculture landscaping

Conventional practice in commercial development of all types is to install generic shrubs and shade trees in a sterile landscape of mounded mulch and turf. One can walk out of almost any office building, school, hotel, or restaurant coast-to-coast, and see the same landscape. Why not devote some of that landscaping cost and effort to trees and shrubs that bear fruit? This is one of the ideas of permaculture, a landscaping practice (the word derived from “permanent” and “agriculture”) pioneered by Bill Mollison of Australia.

While there are plenty of examples of homeowners replacing their lawns with edible landscapes (and a number of excellent books on this topic),

EBN was—remarkably—unable to find any examples of commercial buildings whose owners implemented an edible landscaping strategy. Why can’t employees at a Florida office complex go outside for a mid-afternoon stroll and pick a ripe orange from a well-managed landscape of dwarf citrus trees? Why can’t schoolchildren and teachers in Yakima, Washington, pick cherries, raspberries, and apples during recess? Wouldn’t this be the “low-hanging fruit” of a transition to more localized food production?

Farming Our Rooftops

For an article in 1998 on low-slope roofing (see

EBN

Vol. 7, No. 10), we calculated that the nation’s 4.8 million commercial buildings had about 1,400 square miles (360,000 ha) of roof, most of which is nearly flat—this is an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. While lots of these roofs are shaded by neighboring buildings, are structurally inadequate to support rooftop activity, or are otherwise inappropriate for use, there are lots of buildings where rooftop gardens or greenhouses could very effectively be used for food production.

Green roofs and container farming

Most green roofs today are created to manage stormwater flows, to reduce the urban heat island effect, to save energy, or to create attractive green spaces. Green roofs can also provide “farmland.”

Portland, Oregon, has been a leader in advancing green roofs (eco-roofs, as they are called locally), so it’s no surprise that some examples of food-producing green roofs can be found there. One of them is the Burnside Rocket building, a new mixed-use green building in the Lower Burnside neighborhood of the city. On the roof, Marc Boucher-Colbert manages about 1,000 ft2 (100 m2) of garden space. Included in this growing space are two small sections of intensive green roof (

intensive green roofs have deeper soil than the more common,

extensive green roofs—which are typically planted with sedums), six 3' x 9' (0.9 x 2.7 m) raised beds, and 39 circular plastic planters made from “kiddie” pools, each about four feet (1.2 m) in diameter. For two years, Boucher-Colbert has been growing a variety of produce for the Rocket Restaurant located on the first floor of the building. (Unfortunately, the restaurant closed in late 2008.)

Boucher-Colbert uses a variety of soil amendments for his organically managed gardens, including kelp meal, glacial rock dust, bone meal, blood, worm casings, and commercially available organic fertilizer. His soil depths vary from about 3" (80 mm) for the round planter beds to 18" (460 mm) in the raised beds. When necessary, he waters beds with a solution including a fish-emulsion and kelp organic fertilizer. His goal is year-round food production, offering chefs a variety of healthy, fresh, seasonally appropriate produce. Along with a variety of herbs, Boucher-Colbert has produced lettuce, arugula, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, summer squash, cucumbers, and various specialty vegetables, such as golden-podded peas.

Using green roofs for food production is not without challenges. Along with the structural loading issues (Boucher-Colbert cautions that one should not follow his example without a thorough inspection by a structural engineer), easy access to the roof is critical. In a multifamily residential or commercial building, occupants may not want urban farmers traipsing with wheelbarrows of fertilizer and muddy tools through a public lobby.

Rooftop greenhouses with soil

Eli Zabar’s greenhouse operation in the Upper East Side of Manhattan illustrates the potential for integrating commercial-scale food production onto rooftops. Significantly more food can be produced over a much longer growing season in rooftop greenhouse operations than with open-air green roofs and container gardens. Zabar’s idea for the greenhouses emerged around 1995 from two of his interests. He wanted to stretch the season during which he could sell fresh, local tomatoes, and he wanted to use the waste heat from a bakery he operates. “When I put the two ideas together, the light bulb went off,” Zabar told

EBN. He currently manages four greenhouses, the largest 40' x 100' (12 x 30 m), with a full-time greenhouse staff of two.

Since he built the first of his rooftop greenhouses, Zabar has always grown in soil. While he has visited lots of successful hydroponic greenhouse operations, he believes that produce grown in soil tastes better. “I’m not interested in hydroponics,” he said. With soil-based growing, he’s also able to make use of compost that he produces on the roof using discards from his market. He has an eight-foot (2.4 m) diameter drum with an auger that is turned regularly to mix the compost. His recipe for compost includes sawdust and bread from his bakery (which supplies about 1,000 restaurants in the city). Zabar would like to compost more of his organic waste but can’t. “We could do a ton more, but there’s a space limitation,” he said.

Ducts from his bakery ovens heat the rooftop greenhouses, providing all of the needed heat for his lettuces and herbs. For tomatoes, he has to supplement that heat to maintain an optimal temperature of 75°F (24°C).

Rooftop hydroponic greenhouses

While Eli Zabar is a strong proponent of soil-based growing, much of the recent interest in rooftop greenhouses has focused on hydroponics, which involves growing plants in nutrient-rich water. This method offers a number of distinct advantages in rooftop applications.

Benjamin Linsley of BrightFarm Systems in New York City (www.brightfarmsystems.com) consults on rooftop greenhouses and claims that hydroponic management is 10–20 times more productive than field agriculture, with far lower water use and higher reliability. After developing the “Science Barge,” a demonstration project with a floating farming component that operated along the Manhattan waterfront in the summers of 2007 and 2008, he shifted his attention to rooftop hydroponic greenhouses. BrightFarm Systems has several hydroponic rooftop greenhouse projects in the queue for construction during the first half of 2009, he told

EBN, and another 15 projects that stand a good chance of moving forward before the end of 2010.

There are three basic hydroponic techniques. With

raft hydroponics, plants are grown on a floating raft with roots extending into nutrient media. This approach adds considerable weight, depending on the depth of the hydroponic tanks, so it is most commonly used in ground-mounted greenhouses, not rooftop applications.

Nutrient film technique (NFT) hydroponics is used for leafy plants, such as lettuce, spinach, and basil; the nutrient solution is circulated through hollow plastic channels that support the plants, and the plant roots hug the surface of the channel to absorb the water and nutrients. This is a recirculation technique; nutrients are added to the solution in the reservoir. Of relevance to rooftop applications is the lighter weight of NFT compared with other hydroponic approaches or soil. The primary weight is the reservoir, which can be located on a portion of the roof that has adequate structural reinforcement—so the entire roof structure may not need to be strengthened.

Dutch bucket hydroponics involves buckets or bags filled with an inert media—such as perlite, vermiculite, or mineral wool—through which the nutrient solution is circulated; this system is used primarily for tomatoes, peppers, root vegetables, and other plants with more substantial stems. In this type of facility, there is greater weight spread throughout the greenhouse, both from the buckets and the plants themselves, which can be quite heavy when fully grown.

Hydroponic farming necessitates precise management—including careful measurement of nutrient concentrations and adjustment of flow rates. Due to its chemical nature, hydroponics has traditionally been harder to manage organically than soil-based agriculture; hydroponic growers need to know precisely how much of various nutrients are being added to the growing solution, and that’s easier to do with synthetic fertilizers. Michael Christian, president of American Hydroponics in Arcata, California (www.amhydro.com), one of the leading suppliers of hydroponic equipment, told

EBN that the hydroponic farming movement has so far been less focused on organic methods. That is beginning to change, though, particularly in Europe.

Aquaponics

Aquaponics is a relatively new approach to food production, combining both recirculation hydroponics and aquaculture (fish production). Some of the earliest research into aquaponics began in the 1970s at the University of the Virgin Islands, where James Rakocy, Ph.D., developed a commercially viable aquaponic system using raft hydroponics. The beauty of aquaponics is that it offers a balanced nutrient cycle that does not require the addition of fertilizers. It also solves one of the significant problems associated with aquaculture: what to do with fish waste.

In an aquaponic system, wastes produced by fish become beneficial fertilizer for hydroponically grown plants. According to Nelson and Pade, Inc., the leading North American firm involved with aquaponics (and publisher of

Aquaponics Journal), ammonia-rich fish wastes are broken down by bacteria into nitrate—the form of nitrogen that plants use. This nutrient solution is used in a recirculating hydroponic system—most commonly raft hydroponics but occasionally NFT or Dutch bucket hydroponics. Due to the weight of fish tanks, aquaculture is rarely a rooftop enterprise, though it would be possible to locate the fish tanks at ground level with NFT hydroponics on the roof.

“Aquaponics has just incredible potential,” Rebecca Nelson, of Nelson and Pade, told

EBN, especially if space is tight. “Even an eighth of an acre [500 m2] could be viable for a commercial operation,” she said, making aquaponics a good option in urban areas as long as there is adequate sunlight for the hydroponics.

Nelson and Pade sells packaged systems for aquaponic farming and provides estimates of annual yield. A small commercial system, occupying a total greenhouse footprint of about 16' x 20' (5 x 6 m) and selling for about $4,000, including all tanks and raft hydroponic trays, is estimated to produce over 180 pounds (82 kg) of fish and 1,500 heads of lettuce (without supplemental lighting) per year.

To date, there aren’t many commercial-scale aquaponic systems operating in North America. One of the most established is AquaRanch Industries in Flanagan, Illinois, where Myles Harston has been working with aquaculture since 1985 and aquaponics since 1992. In twelve 1,200-gallon (4,500 l) fish tanks and eight hydroponic trays measuring 4' x 150' (1.2 x 46 m) in a 12,500 ft2 (1,200 m2) greenhouse, AquaRanch grows tilapia (a freshwater fish favored by aquaculturalists because it does well in low-oxygen, cloudy water) and a wide variety of vegetables including lettuce, kale, chard, herbs, tomatoes, and hot peppers. All of the company’s vegetable produce is certified organic, and Harston is hoping to become certified for organic fish production as soon as that standard, currently under development, is finalized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Demand is strong for AquaRanch’s tilapia filets and organic produce, which the company sells through its website. “We are having trouble meeting the demand,” Harston told EBN.

Growing food inside buildings

What about growing food

inside buildings? It’s an idea that has been gaining some attention. BrightFarm Systems is advancing an idea it refers to as the Vertically Integrated Greenhouse. Linsley explained that this technique was originally developed to be incorporated between the layers of glass in a double-skin façade of a commercial building, a system that is more common in Europe than North America. Plants would be grown in little pockets on a vertical frame and managed hydroponically; the inner glazing would separate the greenhouse area from the occupied space.

BrightFarm Systems suggests that the same idea could be implemented on the

inside of the glazing, and the company has built a prototype. Some experts

EBN spoke with expressed their doubts about the wisdom of that approach, though. Vern Grubinger, Ph.D., an Extension professor and sustainable farming specialist with the University of Vermont, argues that living or working with a relatively small number of house plants is fine, “but when it comes to growing food crops in the home or office, the mismatch between what makes humans and plants comfortable can be problematic.” For optimal production, Grubinger says that crops generally require higher humidity, stronger light levels, and hotter temperatures than one finds in occupied buildings. In addition, managing the fertility and pest issues with crops often means applications of materials that people should limit their exposure to. “In short,” he says, “good fences make good neighbors, and in this case the fence is a wall.” Linsley acknowledges potential conflicts and suggests that xeric (dry-loving) herbs may be most appropriate inside buildings. (For more on plants in buildings, see

EBN

Vol. 17, No. 10.)

Chickens and livestock in the city

Believe it or not, chicken farming is gaining steam in lots of cities nationwide. Programs in New York City and Portland, Oregon, encourage homeowners to raise hens for egg production (roosters are usually illegal due to noise concerns). Just Food, the nonprofit organization in New York City that has operated The City Farms community gardening program since 1997, launched its City Chickens program in 2006 and publishes

The City Chicken Guide. Raising hens complements community gardening programs because of the fertilizer chickens produce.

Laws relating to keeping chickens vary widely. In some cities, such as Boston and Toronto, chickens are banned outright. Other cities, such as Seattle and Baltimore, limit numbers and prohibit roosters. Often there are setback requirements from neighbors, and Minneapolis requires that applicants get approval from 80% of neighbors within 100 feet (30 m). Chicken laws for several hundred cities can be found at www.thecitychicken.com.

As with chickens, there is growing interest in raising bees in some cities. While Boston prohibits chickens, it is one of a number of cities that encourage beekeeping to aid in pollination (others include Chicago, Seattle, Dallas, and San Francisco). Though New York City currently bans beekeeping—classifying bees as “wild and ferocious animals” (along with lions and alligators)—there is an active effort in the city to overturn that designation. Awareness of the value of bees has increased as a result of Colony Collapse Disorder, which has devastated commercial beehives throughout the country.

Raising livestock and poultry for meat is less common in cities, though some large cities permit livestock. Growing Power, an urban farm in Milwaukee, raises ducks and goats for slaughter, the latter serving many of the city’s ethnic communities. Growing Power also uses goat milk to make artisan cheeses.

Vertical farms

Some suggest that the ultimate in urban farming will be high-rise farm buildings that might produce everything from algae-based biodiesel to salad greens, eggs, beef, and milk. Magazines such as

Time, Popular Science, and

Scientific American have been rife with articles on this futuristic model of farming. Some articles have even suggested that our meats will be produced in industrial laboratories through cloning of cell tissue—animals won’t even be required.

Dickson Despommier, Ph.D., a professor of Environmental Health Science at Columbia University, has been a leading proponent of this concept through his Vertical Farm Project (www.verticalfarm.com). As an exercise in evaluating possibilities, this is a fascinating discussion, but as a practical reality, it is difficult to imagine that the infrastructure costs of multi-story, vertical farm structures could be even remotely economical. The model also promotes the kind of factory process that many food experts say we should move away from. We’ll leave this discussion, for the time being, to science fiction.

Final Thoughts

Integrating food production into the built environment—from community gardens on empty lots to rooftop hydroponic greenhouses and aquaponics—offers an opportunity to reduce the energy intensity of our food system. This urban and suburban agriculture seems like a new idea, but the basic idea isn’t new at all. A few short generations ago, prior to the industrialization and regionalization of agriculture, local food production was a way of life in America and elsewhere. And in the 1940s, during World War II, Americans were convinced to plant “Victory Gardens,” and they did so by the millions. In 1943, 20 million Victory Gardens produced 40% of America's fresh vegetables, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Local food production also affords what could prove to be a critically important level of self-sufficiency in an uncertain world. Just as the issue of passive survivability (see

EBN

Vol. 17, No. 4) addressed why and how to create buildings that will maintain livable conditions in the event of extended loss of power or heating fuel or shortages of water, producing more of our food locally offers a level of security we don’t have today. Hopefully, this won’t become necessary, but the chance that it might should be a strong incentive to move in this direction.

– Alex Wilson

For more information:

City Farmer

www.cityfarmer.info

Just Food

www.justfood.org

Nelson and Pade, Inc.

www.aquaponics.com

Sky Vegetables, LLC

www.skyvegetables.com